Thorold Dickinson

In his Biographical Dictionary of Film, David Thompson has a very brief entry on the English director Thorold Dickinson. He implies that Dickinson was a kind of failure, unable to make films and so turning to teaching. Thompson sees him as a sad character, his talent wasted on unworthy students no doubt unaware of who their mentor once was (these apparently included noted critic Raymond Durgnat and the filmmaker Don Levy [Herostratus, 1967]). This seems rather a harsh view, but there are definitely questions raised by Dickinson’s small, sporadic output. From his first feature, High Command in 1937, to his final film, Hill 24 Doesn’t Answer in 1955, he made only nine features, plus a number of training films during the war.

Dickinson was kicked out of Oxford University in his final year because his interest in film caused him to neglect his studies. He took on various jobs in the industry, becoming a writer and editor before directing. As supervisor of technical operations for the London Film Society throughout the ’30s, he became familiar with European and Russian practice, helping to introduce the work of Vertov, Eisenstein and others to British audiences. In 1936 he became vice president of the Association of Cine-Technicians and the next year went as a delegate to study the Soviet production system. He made a couple of documentaries in Spain for the Republican side in the Civil War and, during World War Two, he set up the British army’s film unit. After making his final feature, he became Chief of Film Services for UNESCO, and then in 1960 he set up the film department at the Slade School of Fine Art in London. The BFI’s biographical sketch of Dickinson sums him up: “whether beyond or behind the film camera Dickinson stayed the eternal outsider, never comfortable in an Establishment niche”.

Given the overall quality of Dickinson’s work and the range of subjects he tackled, it seems clear that he would probably have been far more prolific if Britain had had a stronger industry back then, something more like the Hollywood studio system which provided secure support for solid, workmanlike filmmakers. But Dickinson began his work as a director towards the end of the “quota quickie” years and struggled to continue through the war and the economic instability of the post-war years. His filmography has an odd, piecemeal look to it, the appearance of a committed filmmaker making do with whatever came to hand.

Lindsay Anderson’s Making a Movie (George Allen & Unwin Ltd: London, 1952), an excellent account of the production of Dickinson’s most personal project, Secret People, reveals the director to be a serious professional, perhaps more craftsman than artist, unquestionably committed to his humanistic principles. And yet his two best known films, Gaslight (1940) and The Queen of Spades (1949), are densely wrought psychological thrillers, packed with period atmosphere and virtuoso camerawork – and neither was initiated by Dickinson himself.

The two films which he worked hardest to get off the ground, and therefore seemingly the ones most important to him, are somewhat earnest and seem to present a thesis perhaps more than an expression of drama. Men of Two Worlds (1946) represented his return to Africa nine years after partially shooting his first feature, The High Command, there; in this film he was concerned to present an African story from an African point of view. According to the British Film Institute’s note on Dickinson, he “poured much of his hopes for education and social improvement into the Technicolor feature film Men of Two Worlds, but its overly worthy air, artificial studio settings, and awkward central character (a European-trained composer returning to face African tribal superstitions) considerably weakened the film’s potential.”

According to Anderson, Secret People (1952: available as a Region 2 DVD from Amazon UK and Amazon sellers in other countries) had a ten-year gestation, Dickinson’s work with the War Office in the early ’40s having generated an interest in the psychological effects of “public violence on the private conscience of a worker for an illegal political organization” (Making a Movie, p. 11). Dickinson set his film in the years just before the Second World War when the rise of fascism in Europe could be seen easily as a justification for violent resistance. The story concerns a refugee woman in London who is drawn by an old friend into a plot to assassinate the fascist leader who had her father killed years earlier. When faced with the death of an innocent bystander, the woman rejects the revolutionary violence which has come to consume her old friend’s life. While beautifully crafted, with fine performances, particularly from Valentina Cortese and Serge Reggiani, the film ultimately finds no solution to the problem of political violence other than a plea that we all just stop hurting each other.

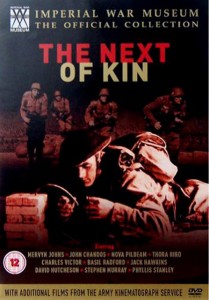

So it seems that Dickinson’s undeniable idealism ultimately didn’t translate very well into film narratives. His work seems far more successful when unencumbered by that educational intention: from the early entertaining quickies, The High Command and The Arsenal Stadium Mystery, through his brilliant propaganda feature The Next of Kin, to the two great period melodramas, Dickinson revealed himself to be a visually adept storyteller with a fine sense of pacing and the ability to generate relentless dramatic tension.

The High Command (1937: on R2 DVD) is a creaky melodrama, featuring adultery, blackmail and murder in a British colonial outpost in Africa, the plot ultimately pointing back to an incident in Ireland in 1921, which we see as a kind of prologue to the main action. There are moments of wit, both crude (the villainous Major Carson raises his handkerchief to blow his nose just as the docking ship’s horn blasts) and subtle (an establishing panorama of the African town dissolves to a closer shot of narrow streets and houses which are an obvious miniature, far cruder than the Alpine village at the start of The Lady Vanishes … but just as you’re thinking this is very bad, a hand reaches into frame and the camera pans up to the seedy trader Cloam who has obviously built the model himself). Despite the clumsy plot mechanics, this first feature allowed Dickinson (despite the censor’s objections to uncomplimentary depictions of the military) to poke fun at colonial pretensions, and provided him with an excellent cast led by Lionel Atwill as the guilt-haunted commanding officer, a very young James Mason as a junior officer and the German actress Lucie Mannheim (fresh from Hitchcock’s The 39 Steps) as the unhappy trader’s wife whose affair with Mason’s character gets the plot rolling.

The Arsenal Stadium Mystery (1939: on R2 DVD) is very different, a throw-away murder story which allows Dickinson to reveal a playful side not apparent in any of the other features. Beginning with a charity football match between the champion Arsenal side and an amateur team, the Trojans, during which the unpleasant Trojan star player drops dead on the field, it follows the investigation of the eccentric Inspector Slade of Scotland Yard (the always entertaining Leslie Banks), and concludes with a re-match during which the Inspector reveals the killer’s identity. The only point of connection between this and The High Command is the plot device of a motive going back to an earlier incident which triggers the murder and the problematic romantic entanglements which drive the main characters’ actions. But here, rather than turgid melodrama, the story is played almost as lighthearted farce.

The Next of Kin (1942: on R2 DVD) began as a training film for military personnel about the dangers of not keeping your mouth shut and evolved into one of the finest propaganda features of the war (the equal of Cavalcanti’s Went the Day Well?) and Dickinson’s finest film after the two period thrillers. This was actually his second contribution to the war effort, the first being the previous year’s Disraeli biopic, The Prime Minister, by all accounts a dull disaster which Dickinson himself disowned. Described by Philip Horne on the BFI website as “one of the most interesting, and thrillingly ruthless, propaganda films of the War”, The Next of Kin is a breathlessly paced yet chillingly matter-of-fact account of preparations for a raid on the French coast. With no-one standing out as a protagonist, it depicts multiple levels of wartime society in which hidden enemy agents manage to piece together military intelligence from seemingly insignificant comments overheard in pubs and shops and other innocuous public places. As an army security man tries to keep the operation secret, leaks spring up all around and the film climaxes in a brutal battle sequence in which most of the commando force is killed by the Germans who knew they were coming and were well prepared. The fast-paced Next of Kin has some remarkable transition effects, giving the narrative a relentless forward momentum which reinforces the idea that casual carelessness causes events to race out of control, leading to disaster. (Ironically, the film was released just a couple of months before the catastrophic raid on Dieppe in which more than half of the landing force were killed or captured in just a few hours, before the remainder were forced to retreat.) Apparently Churchill wanted the film suppressed because it was too much of a downer, so a brief epilogue was added to explain that the mission itself was accomplished, though at a terrible cost in lives.

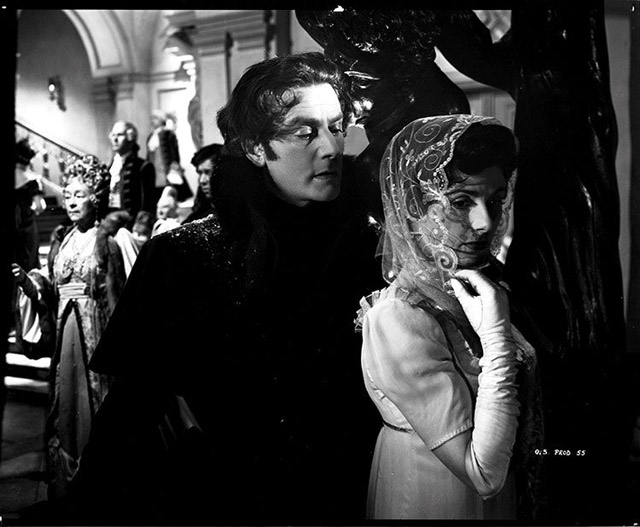

Gaslight (1940: on R1 DVD), the first adaptation of Patrick Hamilton’s successful play, is Dickinson’s finest work. And for some time, it was virtually a lost film because when MGM bought the remake rights for their 1944 version, part of the deal was that all copies of the British original had to be destroyed to eliminate competition. Luckily, someone somewhere had the foresight to preserve the film and we can now see just how superior it is to George Cukor’s version. Like Victor Fleming’s 1941 MGM remake of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, what Cukor’s movie adds in production values and technical gloss, it loses completely in atmosphere and nuance; Charles Boyer has none of the menace of Anton Walbrook as the foreign husband trying to drive his wife mad in order to conceal his real identity, and Ingrid Bergman is far too glamourous a movie star to convince as the neurotic woman who no longer has the strength to believe her own perceptions. In Dickinson’s film, there’s a much sharper sense of the class issues underlying the story, the contempt of bourgeois society for the foreign upstart and his consequent hatred for the wife whose money he had hoped would buy him into that society.

It’s interesting to note the strong similarities between this and Dickinson’s other great film, The Queen of Spades (1949: out-of-print R1 DVD), adapted from Alexander Pushkin’s story of an impoverished Russian officer who seeks to steal the secret of winning at cards from a sinister old countess who is reputed to have sold her own soul years ago for that same secret. Strangely, both these films were taken on by Dickinson at short notice – Gaslight just three weeks before shooting began, Queen of Spades on a mere three days notice. Both star Anton Walbrook in what are possibly his two finest performances, in both cases as an outsider driven mad by his desire to obtain enough wealth to buy his way into a social circle which treats him with contempt. Given the strength and intensity of these performances, it’s perhaps tempting to speculate that Dickinson felt some degree of identification with this outsider figure prevented by social and economic forces from reaching what he believed to be his full potential.

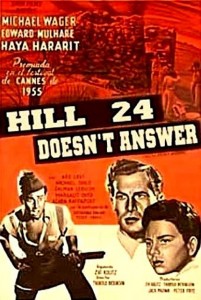

After Secret People met with little success, Dickinson made only one other feature. Initially he only accepted the role of adviser for what would become the first feature made in the new state of Israel, but as the project got underway, he assumed the responsibilities of director. Hill 24 Doesn’t Answer (1955: on R1 DVD) is an interesting but uneven film, the story framed around the last night before the truce which would establish the borders at the end of the war of independence in 1947. Focusing on a handful of fighters assigned to hold a small hill outside of Jerusalem so that the new state could lay claim to that small piece of land, we flash back to the individual stories which have led each of them to this point: refugees from Europe who defied the British authorities in order to create their own nation, an American who came as a tourist but stayed on to fight, and a British policeman who came to see that he was on the wrong side in this struggle. Inevitably, the film fits into the category of pro-Israeli propaganda (there’s no mention at all of displaced Palestinians), and there are thuddingly didactic moments along the way, but Dickinson stages the various combat scenes well, in particular the street fighting in Jerusalem during which the American briefly loses his faith in the cause.

So … was Thorold Dickinson a major filmmaker? … an interesting oddity? … the sad failure implied by David Thompson? As with any director, in the end all we have are the films themselves. And on their evidence, perhaps all we can say is that it’s a pity he wasn’t able to make more than these nine.

Comments