DVD (actually Blu-Ray) of the Week: Battle Royale (2000)

It was unfortunate that until the very end of his career, the Japanese director Kinji Fukasaku was known in North America mostly for his worst film: The Green Slime. This was an “international” production, shot in Japanese studios with an American and European cast, a very bad script and even worse special effects. But even with all that against it, it might not have seemed quite so bad if it hadn’t been released the same year as Kubrick’s 2001 and Schaffner’s Planet of the Apes.

The fact is, though, that science fiction wasn’t Fukasaku’s strong point. His Message From Space (1978) almost makes your head hurt with its bizarre mix of Japanese folk tale and Star Wars rip-off: a dying people, seeking help to fight the evil metallic race which has conquered and pillaged their world, send eight magic seeds into space to find special warriors to help them: those warriors turn out to be a group of hot-rodding space buddies, a disillusioned soldier and his cute robot, and an exiled warrior from the invading race. Images of a giant battle cruiser pursuing an ethereal square-rigged space galleon sailing among asteroids simply do not compute for a western viewer (and who knows, maybe not even for a Japanese viewer).

The best of Fukasaku’s mid-career SF films was 1980’s Virus, another international production which fits into the mold of the time: big multi-national cast, world-spanning disaster (a plague which kills off everyone except a few hundred in Antarctica), but it’s one of the best of its genre – epic-scaled, sombre, and impressively mounted.

Fukasaku did better with Samurai films, including a number featuring Sonny Chiba (who was also Doctor Tamauchi in Virus). Some of these were fantasies, like Legend of the Eight Samurai (1984) and Samurai Reincarnation (1981); others were historical, like Shogun’s Samurai (1978) and Swords of Vengeance (also 1978). This last is Fukasaku’s version of the much-filmed tale of the Loyal 47 Ronin, based on an actual incident enshrined in Japanese lore as a signature lesson in honour and loyalty – after their lord is ordered to commit seppuku, the now-masterless samurai (ronin) eventually avenge his death and then ritually commit suicide themselves. Fukasaku faced a lot of conflict with his traditionalist star, Kinnosuke Yorozuya, who wanted to play the story straight. But Fukasaku nevertheless managed to subvert the revered tale by turning the ronin’s revenge into a bloody massacre, so long delayed from the supposed inciting incident that it becomes an expression of lawless savagery.

This points the way to the most significant aspect of Fukusaku’s work, which encompassed many genres and finally amounted to more than sixty features. As a child, he grew up during the period of intense militarization in the 1930s and as an adolescent towards the end of the war he was put to work in a munitions factory, where he saw many friends die in bombing raids. After the war, when he saw the society around him (which had previously worshiped the Emperor as a god and been willing to die to serve him) suddenly throw off that lethal philosophy under the influence of the American occupation, he lost all respect for authority.

Angered by the hypocrisy which underlay the Japanese economic recovery, Fukusaku eventually found the perfect vehicle to channel his attitudes: the yakuza film. Throughout the ’60s, the ninkyo eiga had been a highly popular genre, a kind of modern substitute for the traditional feudal tales which had been frowned on by the occupiers as representing the social attitudes and structures which had led to the militarization of the ’30s. In these films, the romanticized gangster hero would be torn by personal loyalties, often devoted to a friend who belonged to a rival gang, and ultimately would sacrifice himself in order to do the right thing. Fukasaku would have none of that, and he began to turn out a string of savagely realistic films in which the economic recovery was paralleled by the rise of large organized gangs which preyed on Japanese society. The foot soldiers in these gangs were violent sociopaths, driven by their own base urges rather than any higher ideals, and the films themselves were firmly rooted in recent Japanese history.

Fukasaku’s masterpiece in this reinvention of the genre was the sprawling five-part series Battles Without Honour and Humanity (aka The Yakuza Papers, 1973-74), which follows a large group of characters through three decades of violence, politics and business. The style he developed for these films is incredibly kinetic, with its use of hand-held camera, radical cutting, archival images and on-screen text creating a dense collage which gives a sense of events moving so fast that no one can possibly control them and from which explosions of graphic violence are frequent and inevitable.

After his intense period of creativity in the ’70s and early ’80s, Fukasaku seemed to go into a bit of a decline, but then at the age of 69 he suddenly came back to cap off his long career with two of his finest works. The Geisha House (1999) seems quite untypical for him, a quiet, elegiac depiction of the end of the traditional geisha system of formalized prostitution in the 1950s, seen through the eyes of an adolescent girl who has been brought into the house of the title to undergo training. This work, more reminiscent of someone like Naruse than the brilliantly savage director of those ’70s yakuza thrillers, was immediately followed by Fukasaku’s final masterpiece, Battle Royale (2000).

Battle Royale, adapted by Fukasaku’s son Kenta from a novel by Koushun Takami, is one of the best works of social science fiction ever filmed. It is also one of the most violent films ever made, but unlike Battles Without Honour and Humanity, it has an almost formal style which somehow contains the violence in such a way as to make it more chilling. Perhaps this approach was necessary because this is also one of Fukasaku’s angriest films and could easily have devolved into chaos and incoherence.

In a very near future, Japan’s economy has collapsed and the social order has decayed. The failures of society have produced a generation of children who no longer “respect” their elders (just as Fukasaku himself emerged from his experiences in the war). Faced with what is perceived by the authorities as a decline in “order”, society has turned against its own young, passing a law whose sole purpose seems to be a kind of self-genocide. Under the BR Act, random classes of high school kids are sent to remote areas where they are forced to kill each other off, with only one permitted to survive – if they fail to accomplish this by the end of three days, all the survivors will be killed.

The film follows the experiences of 42 students transported to a remote island, supplied with a variety of weapons, and forced to face the inevitability of their own deaths. It’s a savage and bloody story, but Fukasaku manages to draw sharp portraits of these kids, giving us access to their emotional lives, their pasts, their reasons for responding to the situation in each of their individual ways. As director Kiyoshi Kurosawa points out in one of the extras of Home Vision’s excellent box set of Battles Without Honour and Humanity, what distinguishes Fukasaku’s use of violence isn’t the visual spectacle, the “thrill”, but the fact that he gets at the intense emotions experienced by both the perpetrator and the victim … you understand both where it’s coming from and what the impact is. In Battle Royale, he constantly blurs the line between “good” and “bad” characters by giving you moments of insight into their actions so that even the seemingly vicious, cold-blooded Mitsuko is revealed as acting out of her own inner pain, suddenly given an opportunity to express her fears and resentments at being abused and ostracized …

In fact, what makes Battle Royale so ultimately chilling is the fact that all the kids’ actions are recognizable as rooted in “normal” high school social behaviour; this society which has collapsed has deliberately removed the norms and controls which limit what people are capable of doing to each other and themselves. Without clear social structures, a simple act of trust becomes almost insurmountably difficult, and fear and anger take control. As bloody as it is, Battle Royale is anything but gratuitous in its dissection of human behaviour in extreme circumstances.

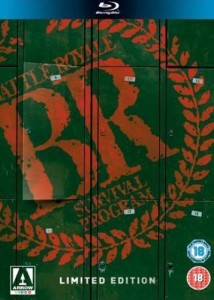

Arrow Films’ region-free three-disk Blu-Ray edition of Fukasaku’s final film is an impressively packaged set which offers both the original theatrical version and the slightly different director’s cut which contains some material shot after the initial release (mostly a series of flashbacks to a happier moment of competition among the characters at a high school basketball game). The extras are a mixed bag, including a rather shapeless hour-long making-of, some interviews and a seemingly random collection of featurettes about various premieres, FX work, and so on. It would have been nice to have some more in-depth critical and contextual material, but the excellent quality of the two versions makes the set more than worthwhile.

Comments