Video Nasties, Part 3

There is a long, if not necessarily venerable, tradition in the arts of creating confrontational, deliberately offensive work to challenge received ideas and to make people conscious of their own conventional assumptions. When work like this is created, it doesn’t make a lot of sense to get indignant at people who are genuinely offended; in fact, that’s the whole point of creating such work. Rather, these reactions should provide an occasion for discussion about the meaning and purpose of the art itself.

While there may be some debate about whether the term “art” can be applied to exploitation filmmaking, this kind of deliberate assault on generally held ideas of good taste is one of the very definitions of exploitation. So, if works displayed in prestigious galleries can bring down the wrath of cultural guardians, it’s not at all surprising that works shown in disreputable grindhouses and on cheap videotape should inspire even greater condemnation. This of course is what happened during the great British video nasty scare of the 1980s. While it’s difficult to see why some of these movies were targeted by the Department of Public Prosecutions, others did seem to invite retribution by being far more self-consciously aware of their transgressive stance.

I’ll deal with three of the most interesting here, all rather unpleasant viewing experiences but nonetheless worth watching if you have the stomach for it:

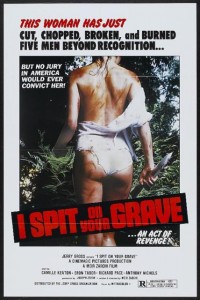

I Spit On Your Grave (Meir Zarchi, 1978)

Rape-revenge movies constitute their own small sub-genre, though how they are categorized often depends largely on their budget and their cast. At the low end of the scale, a movie is likely to be labelled as exploitation (Ms. 45: Abel Ferrera, 1981); with higher production values, it might be labelled as a thriller or suspense movie (Sudden Impact: Clint Eastwood, 1983); and at the top of the scale, as a social issues drama (The Accused: Jonathan Kaplan, 1988). This genre encompasses a range that includes the glossy Lipstick (1976), Extremities (1986), and even to a degree Deliverance (1972), which of course offers the variation of a man being the rape victim. But as distasteful and exploitative as some of these movies are (even the Oscar-winning The Accused, which in classic exploitation style structures itself as one big build-up to the long climactic flashback of the rape itself), none have had such critical bile poured on them as I Spit On Your Grave (1978).

The storyline is extremely simple: Jennifer Hills, a writer from New York, retreats to a cottage by a river to work on her novel; a bunch of local guys led by a gas station attendant, and including his two unemployed friends and a simple-minded grocery delivery boy, see her as an easy target and attack her, raping her repeatedly and leaving her for dead; she recovers and then, one by one, kills each of her attackers.

Roger Ebert went apoplectic about this “vile bag of garbage”, while Mick Martin & Marsha Porter’s Video Movie Guide called it “An utterly reprehensible motion picture with shockingly misplaced values.” (This guide gave high ratings to Dirty Harry and Rambo: First Blood II, much more polished, bigger budgeted exercises in vigilantism and gratuitous violence.) But can the often low-budget crudity of Zarchi’s style by itself explain the reaction to Spit? Mike Sutton at The Digital Fix points out that “Meir Zarchi’s much despised I Spit On Your Grave offers something very rare – a hellishly long rape which is deliberately presented from the point of view of the victim with camera angles that are, to the best of my knowledge, almost unique in the way they emphasise the dehumanisation of the rapists as the victim sees them.” Obviously the extremely gruelling, unpleasant and protracted assault on Jennifer is really hard to watch. But what distinguishes this sequence from so many other films of this type is the absolute refusal to offer even a hint of eroticism, even the slightest suggestion that this is some kind of sexual experience for the woman. Strangely, Martin & Porter assert that the movie “seems to take … joy in presenting its heroine’s degradation” – a very peculiar reading of what is actually shown on screen.

Carol Clover, in her excellent examination of modern horror films, Men, Women and Chainsaws (Princeton University Press, 1993), gives the movie a detailed, nuanced reading centred on the idea that what makes Zarchi’s efforts so disturbing is the fact that his movie strips this particular genre to its bare essentials and thus reveals ideas less apparent in more heavily encoded versions of the narrative. The rape is presented not as a specifically sexual act, but rather as a male bonding ritual, something equivalent to a team sport, in which the woman serves as a device by which the members of the group can prove themselves to each other. Where so many movie depictions of rape are undeniably voyeuristic, Zarchi’s approach is closer to uninflected documentary observation, and as such the horror of what is being shown is inescapable. To say the least, it’s strange that the slicker, more voyeuristic depiction of rape in The Accused is far more acceptable to the mainstream. But of course, Spit is quite unabashedly an exploitation film and it makes no effort to send its protagonist through the legal system to get redress for what was done to her; she exacts her own brutal revenge – and the movie makes it clear that her own acts of violence restore her, that through them she regains an inner strength that the rapes had stripped from her. It’s also interesting that some commentators, including Martin & Porter, seem to find what she does to her attackers far worse than what they did to her; in the Video Movie Guide, they state that what she does to the leader of the gang “is one of the most appalling moments in cinema history” – a comment which Clover rather drily says “is itself a pretty appalling testimony to the double standard in matters of sexual violence.”

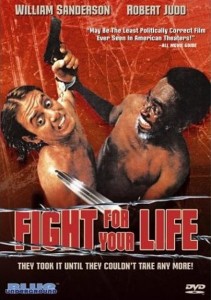

Fight For Your Life (Robert J. Endelson, 1977)

Robert J. Endelson’s Fight For Your Life (1977) is uncomfortable to watch for very different reasons and, in fact, is probably the only one banned by the DPP more for what is said by the characters than for what they do. As I Spit On Your Grave was often condemned for “glorifying” rape, Fight was frequently condemned for being racist. Given the narrative trajectory, this seems patently incorrect; however, at its centre is a viciously racist character whose dialogue is relentlessly offensive and unpleasant to hear. Just as it’s hard to believe a viewer would find any encouragement in Spit to commit rape, it seems highly unlikely that anyone would want to identify with Fight‘s racist villain. The idea that these movies would encourage viewers to imitate what is presented on screen illustrates the condescension, even contempt, that censors inevitably hold towards the people they claim to be “protecting”, the belief that the weak-willed masses have no defence against pernicious influences.

Three escaped convicts, led by the usually mild William Sanderson, break into the remote house of a black minister and his family and begin to torment their hostages with every imaginable kind of racial abuse. The family’s Christian principles require them to be meek in the face of this assault, but eventually the situation escalates to the point where they have no choice but to fight back or be destroyed.

Perhaps in addition to the barrage of offensive language, Fight For Your Life was also condemned because it makes it quite explicit that the family’s adherence to Christianity is actually keeping them down, preventing them from standing up to the white oppressor. This couldn’t be made more clear than in the scene where Sanderson’s Jessie Lee Kane viciously beats Robert Judd’s Reverend Ted Turner about the head with a Bible. The family ultimately have to throw off their piousness in order to fight back if they want to survive – and by the time they do, the pressure has built to such an intensity that it’s a huge relief for the audience to see the bad guys get theirs. Not surprisingly, the film was very popular with inner city black audiences (which, come to think of it, would also give cause for the authorities’ unease).

Both Fight For Your Life and I Spit On Your Grave present oppressed sections of society (African-Americans and women respectively) who suffer extremely brutal treatment (from white men whose unearned power is rooted solely in their whiteness) before rising up to defend themselves in violently assertive ways. And perhaps that alone would be enough for the censors to ban them.

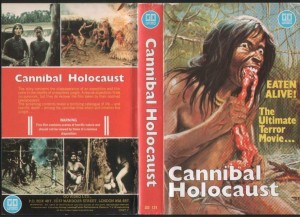

Cannibal Holocaust (Ruggero Deodato, 1980)

Probably the most famous entry in the Italian cannibal genre, Ruggero Deodato’s Cannibal Holocaust is a different proposition altogether, more complex and in some ways more problematic. In effect, this was the original “found-footage” horror movie, an obvious precursor to Blair Witch and its imitators. It also happens to be a self-conscious critique of the media and the hypocrisy of the developed world towards Third World “primitives”.

A film crew has disappeared in the Amazonian forest and an anthropologist follows their trail, encountering hostile natives, and eventually discovers the crew’s remains along with several cans of exposed film. The second half of the movie consists of this raw footage, depicting the increasingly reprehensible behaviour of the film crew as they try to come up with more sensational material. This is rather nasty stuff, featuring disturbing moments of brutality in which the fictional filmmakers eventually become implicated; they end up committing atrocities themselves against the Indians and are, in turn, brutally killed.

Because of Deodato’s impressive skills as a filmmaker, he manages to create a convincing illusion that the “found footage” is genuine documentary material – as a result of which many people believed Cannibal Holocaust was actually a snuff movie. He creates this illusion by making the footage deliberately rough and flawed (a technique now much overused and far more familiar than it was in 1980), but also by including very real violence to animals, with a number of creatures, including a giant sea turtle, being slaughtered on camera and eaten. This serves to provide a queasy background for the very convincing effects of violence to the film’s human characters; the viewer is tricked into believing that everything is real.

The contradiction between the film’s condemnation of media which exploit and even create atrocities for profit and its own use of genuine atrocities (towards the animals) as a device for heightening its own impact is one of the elements which make it simultaneously dramatically powerful and conceptually problematic. The viewer is operating here on two levels, the resulting friction deepening one’s sense of disturbance. This effect is also magnified by the film’s aesthetic beauty in combination with the horrific content of many of the images. There is a very real sense in which Cannibal Holocaust is seriously hypocritical in its critique of media hypocrisy, but paradoxically, because of Deodato’s considerable abilities as a director, rather than collapsing under the weight of this contradiction the film actually becomes more powerful, more disturbing, engaging on an intellectual as well as a visceral level.

These three very different movies were all banned by the DPP in the ’80s. Fight For Your Life is still banned in Britain, while Cannibal Holocaust and I Spit On Your Grave were eventually passed by the censors only after extensive cuts were made. The irony is that what is problematic about each of them is so deeply woven into the fabric of the films that cutting out individual moments and images can’t really defuse what makes them troubling or dangerous. But what’s wrong with being disturbed, even offended? You don’t have to like something in order to get value from it.

Comments