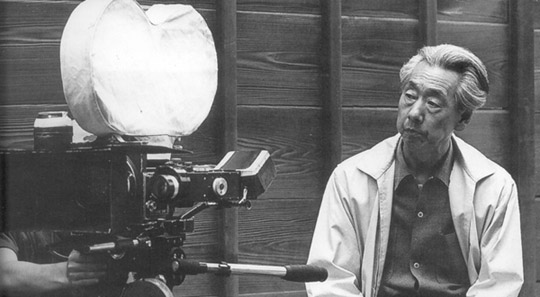

Mikio Naruse

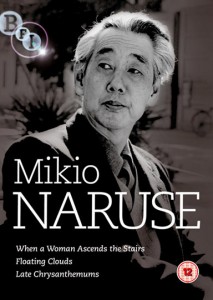

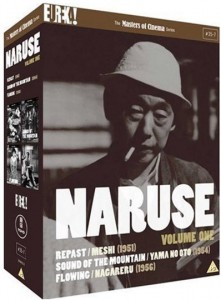

In her January 1 post, the Self-Styled Siren pays homage to the Japanese actress Hideko Takamine, who died December 28 at age 86. The Siren’s warm comments immediately sent me off to watch When a Woman Ascends the Stairs (1960), which Takamine stars in as the bar hostess Keiko. I’m slightly embarrassed to say that I hadn’t gotten around yet to watching what is perhaps Mikio Naruse’s best-known work (here in the West), despite his having become my favourite classical Japanese director just last year. Although there are many of Ozu’s films now available on DVD (largely thanks to an on-going commitment by Criterion), and Masters of Cinema has been making a kind of mini-industry out of releasing Mizoguchi’s work – and, of course, pretty much everything Kurosawa ever did is now easily accessible – there are currently very few of Naruse’s features available on DVD: three-disk sets from both the BFI and Masters of Cinema, plus Criterion’s When a Woman Ascends the Stairs (which has much better subtitles than the BFI edition).

Critically, here in the West, Naruse is generally not rated as highly as the three directors mentioned above and I have to wonder whether that isn’t at least partly due to the fact that he made “women’s films” – after all, how many decades did it take for Douglas Sirk to be taken seriously for that very reason? Australian academic Freda Freiberg, who is featured on all three disks of the BFI’s Naruse set, asserts that it is largely because Naruse’s films lack the Zen spiritual qualities which we like to associate with the East; Naruse was an unsentimental realist, his subject most often the small, daily struggles of women in Japanese society, centred on the pressing need for money to survive. In When a Woman Ascends the Stairs, only opening her own bar or entering a marriage can save Keiko, although the earlier Repast (1951) and Song of the Mountain (1954) indicate that life is just as tough for a married woman. And, as in Woman, the characters in Flowing (1956) and Floating Clouds (1955) are just a breath away from becoming prostitutes … Naruse’s films are bleaker than Ozu’s because they don’t offer a sense of transcendent hope to offset the pain of existence, offering instead a kind of austere, female noir …

As Freda Freiberg puts it in an essay on the Senses of Cinema site (reprinted in the booklet accompanying the BFI set):

“Naruse is a materialist par excellence. There is no escape from the world as it is. Life is a school of hard knocks. We all have to face up to disappointments, betrayals and loneliness, and yet keep on going on. His is a world of disillusion, not illusions. Of survival, not suicide or other more comforting forms of self-transcendence – such as religion, aesthetics, or poetics. In Naruse’s world, there is no transcendence, only daily bodily existence subject to social and economic conditions.”

It’s this sense of reality which I like about his work, the feeling that his characters are closer to us than the people in Ozu’s films who seem to glow with charm even as they suffer (but don’t get me wrong; I love Ozu’s work as well). As Naruse’s women cling to life, even if (as in Floating Clouds) the effort is ultimately too much for them and they die, their very human determination to survive against the odds seems strangely hopeful and the films offer a kind of visceral, rather than aesthetic, pleasure.

Comments