Peter Yates (1929-2011)

Peter Yates died in London on January 9, aged 81. His two best-known films were Bullitt (1968) and Breaking Away (1979), and that perhaps indicates why he was not as widely known as many of his contemporaries. He directed a wide range of movies in many different genres, and for that reason never established a clear “directorial personality”. He was an accomplished, workmanlike filmmaker but there is no consistent identity to his filmography.

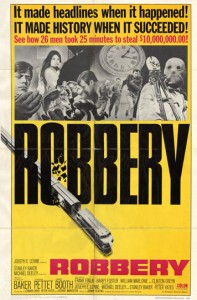

Yates’s first feature was the Cliff Richard musical, Summer Holiday (1963), followed by an obscure Eric Sykes comedy, One Way Pendulum (1964), and several years of television work (The Saint, Danger Man), before making his real breakthrough with Robbery (1967). That thriller, produced by and starring Stanley Baker, based on the infamous 1963 Great Train Robbery, so impressed Steve McQueen that he brought Yates to Hollywood to direct Bullitt, the story of a jaded San Francisco cop out to get the criminal responsible for killing a witness in his custody.

Bullitt turned out to be one of the key films of the ’60s, lean, laconic, its stripped down narrative defining character through action. While the famous ten-minute car chase was ground-breaking at the time, it has less impact now because of all the action which has come since – the streets are too obviously cleared to make way for the stunt cars; the same Volkswagen turns up on street after street, becoming a distraction. In that sense, Bullitt lacks the frenetic “realism” of, say, The French Connection, but what has not often been duplicated is the careful dramatic structuring of Yates’s chase sequence, which starts slowly and quietly and steadily, inexorably becomes an analogue for Bullitt’s mounting obsession, ending with the fiery explosion of a gas station in which the men he’s pursuing die.

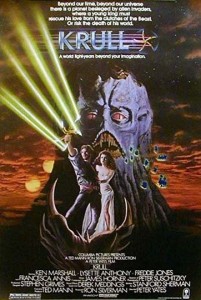

After the success of Bullitt, Yates remained in the States and directed almost two dozen features in the next 35 years; a mix of romance, comedy, action, and character-driven stories, some more successful than others. Movies like Mother, Juggs & Speed (1976) and The Deep (1977) have little to offer; The Hot Rock (1972) is a pretty good caper comedy based on a Donald E. Westlake novel, and Breaking Away has genuine charm. Krull (1983) served only to prove that Yates had absolutely no affinity for fantasy, while The Dresser (1983), an adaptation of Ronald Harwood’s play, provided Albert Finney with one of his thickest slices of ham. Yates’s finest film is the bleak, low-key The Friends of Eddie Coyle (1973), a grim tale of small-time Boston hoods which provided Robert Mitchum with the crowning achievement of his career.

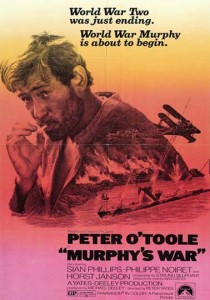

My personal favourite, however, is 1971’s Murphy’s War, a film which doesn’t have much of a reputation. This World War Two story stars Peter O’Toole in full neurotic flight as merchant seaman Murphy, who has survived a U-Boat attack on his freighter and washed up on the banks of the Orinoco River in Venezuela, where a Quaker doctor (Sian Phillips) nurses him back to health. She tries to soothe his desire for revenge, but having witnessed the massacre of his crewmates in the water, the only thing he can think about is destroying the submarine which, by chance, he discovers is hiding out in that same river.

Much of the film is taken up with his plans – finding and repairing a seaplane which has crashed in the jungle, eventually using a rusty old river barge in his final self-destructive attack. While the doctor tries to reason with him, to get him to see that revenge will accomplish nothing other than the loss of his own soul, the fact is that the war has already destroyed his soul – what he has seen and suffered through has hollowed him out and the only thing keeping him alive is the desire to destroy what has now become a very personal enemy.

I can remember reading at the time of the film’s release at least one review which was deeply offended that Murphy actually goes through with his plan, because just as he sets out word arrives that the war has ended, and suddenly his attack on the sub has lost “legitimacy”. Roger Ebert, in his review, goes so far as to say that “It’s possible, I suppose, that the sub deserves sinking, but all the deaths it’s responsible for are legitimate wartime killings; there aren’t any atrocities” – which seems a bit odd as the movie opens with the submarine’s crew machine-gunning merchant seamen to death in the water. Ebert goes on to say that because Murphy has so obviously gone mad, the audience can’t sustain any interest in his actions, but this seems to me to miss the entire point of the film: that it’s impossible to separate individual psychology out from the state-sanctioned violence of war. Having immersed Murphy in this violence, having subjected him to horrific trauma, how reasonable is it to ask him to turn off his own violent impulses at a moment’s notice?

I think Murphy’s War is a great, underrated movie.

Now, I just wish someone would get around to releasing a decent edition of Robbery on DVD. (At long last Robbery was given an excellent Blu-ray release by Network in England in late 2015.)

Comments

Just so you know Ken that was a line from Murphys war.

“Cover Him Up And Say Some Words” – Murphy