The Genius of Matthew Rankin

Given that this week filmmaker Matthew Rankin is back at Sundance with a short film for the second time in three years, he would probably be annoyed if I mention that I first encountered him as an odd, ferociously precocious 14-year-old, when he walked into the offices of the Winnipeg Film Group intent on signing up for the Basic Filmmaking Workshop. That was back when I ran the training program for the WFG in the early ’90s. I may be wrong, but I believe Matthew was probably the youngest person we had ever had in that popular workshop – and I was initially concerned that he would be too young to fit in.

But he stuck with it, and a couple of years later set out to make his first film (Daft, 1997). This was an attempt to emulate Rowan Atkinson’s Mr. Bean comedies, and although a lot of time has passed since I saw it, I recall that it was competent if undistinguished. As with so many young first-timers at the WFG, I don’t think there was any distinctive evidence at the time that Matthew would be more than an enthusiastic amateur. Then he moved away to go to school, studying history and film, eventually getting his degree in Quebec before returning to Winnipeg to form L’atelier national du Manitoba with Walter Forsberg. Together they set about excavating the underbelly of Winnipeg culture with a series of collage/documentaries like Death By Popcorn (on the demise of the Winnipeg Jets) and Kubasa in a Glass (on the strange world of Winnipeg TV advertising). (Kier-La Janisse has an excellent interview with Matthew at screenanarchy.com.)

I think I first realized that Matthew had evolved into a very talented filmmaker when I saw his brief Self-Portrait a few years ago. Made entirely with a cell phone, parodying Kiarostami’s Close-Up, it packs more wit and invention into three minutes than you get in many features.

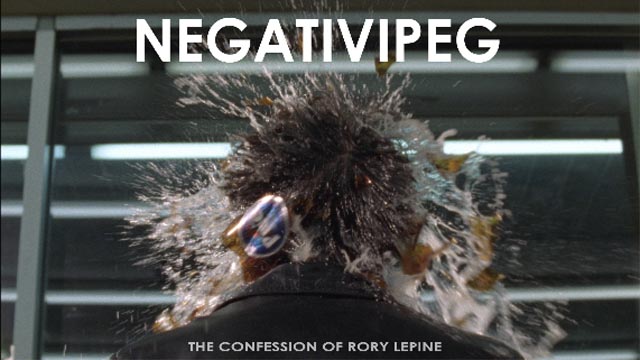

Then two years ago, Matthew was at Sundance with a 4-minute animated short called Cattle Call, made with fellow Winnipegger Mike Maryniuk. This year he got into the festival with his latest film, the documentary/essay Negativipeg, which continues his contemplation of the bizarre complexities of his hometown’s fraught sense of identity.

Negativipeg is a remarkably dense, layered 15-minutes recounting an incident which occurred in 1985, and the perceptual fallout which resulted from it. Late one evening at a North End 7-Eleven, a probably intoxicated 18-year-old named Rory Lepine wanted to buy a pizza pop. A store employee informed him that he was barred from the store and an argument ensued. At which point another customer told Lepine to “get the fuck out of the store”. Unsurprisingly, things deteriorated from there, though the actual course of events isn’t entirely clear – who pushed who, who threw the first punch, that kind of thing. It all ended with Lepine breaking a beer bottle over the other customer’s head and putting the boots to him.

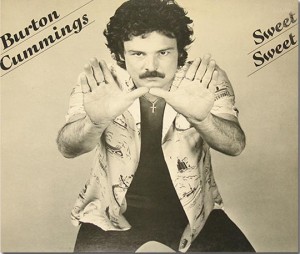

None of this would have been particularly notable except for one thing: the customer at the receiving end of Lepine’s assault happened to be Burton Cummings, a North End boy himself and one of Winnipeg’s bona fide celebrities, former lead singer of The Guess Who and, along with Neil Young and Randy Bachman, Winnipeg’s gift to Rock. And so what would otherwise have been just another late night scuffle in the North End became something else: Cummings perceived it as an affront to his celebrity (even though Lepine didn’t have any idea who it was he was kicking) and chose to lash out at the entire city for not respecting him and his accomplishments. In a public statement he called the city “Negativipeg” and said he no longer belonged here. This in turn caused offence to Winnipeg Free Press columnist Gordon Sinclair, who wrote a column basically saying good riddance. As Morley Walker, another Free Press writer, says in the film: “we want to be loved, and that’s the tragedy of Winnipeg.”

If it hadn’t been Cummings in the store that night, Lepine would be as unknown as any other inhabitant of the North End who happens to get into a drunken brawl; but because Cummings was there, Lepine became a kind of mirror-image celebrity, the guy who didn’t make it out the way Cummings had. They became inextricably linked as a joint symbol of possibility and failure, what holds people back and what, if they’re lucky, they might escape from and become.

In Matthew’s tightly structured account of the event – shot and edited with a knowing nod to Errol Morris and The Thin Blue Line – we see the strange dance of insecurity and need which feeds on itself to generate a perfect storm of love-hate for the city. An interview with Lepine, a typical North End character, apparently smoking a joint as he speaks casually to the camera, aware of the strange celebrity he achieved with that one convenience store encounter (for which, at age 19, he went to jail for four months), is intercut with some footage of Cummings performing at a community centre, plus some skillfully shot and edited re-enactments to which we return again and again, building to a visually witty climax in which the film’s other interview subjects (Sinclair, Walker, Cummings fan Mike Wishnowski) seem to witness and react to the actual bottle strike which brought this moment of civic self-awareness into focus.

Throughout the film, Matthew returns repeatedly to bleak, wintry images of boarded up houses and buildings in the North End, a kind of silent visual chorus suggesting that the city’s inability to get beyond its own thin-skinned feelings about a perceived lack of respect is not merely undermining its potential for greatness, but is actually choking the life out of it. The final feeling with which Negativipeg leaves the viewer is one of rueful sadness, the inescapable conclusion that Winnipeggers – with their endless eagerness to be loved and respected and their deep-rooted fear that they aren’t – are, in fact, their own worst enemies.

Negativipeg screens five times at this week’s Sundance Film Festival.

Comments