The Roxy Theatre, Neepawa

When I moved from Newfoundland to Manitoba in the spring of 1973, I spent the first two months in the small town of Neepawa – a community of about 4000, 110 miles north-west of Winnipeg. There wasn’t much there; mostly a lumber yard and numerous farm equipment dealerships. But it had both a movie theatre and a drive-in. The drive-in, of course, was only open in the summer, and maybe then only on weekends (I didn’t go often, and it closed sometime in the late ’70s, I think); it was located a mile or two west of the town and after they replaced the window speakers with a system that let you hear the sound over your radio, you could actually park on the shoulder of the highway and watch without paying. It had been built, sensibly, with the screen facing east so that it wasn’t washed out by the setting sun – but that also meant that it was clearly visible from the road.

The Roxy, at 291 Hamilton Street, was built in 1906. It was originally called the Opera House, and apparently was “the social hub of the community” (according to the town’s website). “In the early 1930s, the Opera House was converted to the Roxy Theatre. In 1936, the exterior was transformed when it was stuccoed in the Art Deco style.” It was a small, box-like building with a tiny lobby, perhaps a couple of hundred seats, and there was still a stage at the front above which hung the screen. The floors bounced when you walked down the side aisles, and you could always smell popcorn in the auditorium. (The Roxy closed for a while in the ’80s, then was reopened as a community-run venue; it still shows movies on weekends, and is used for local drama productions.)

What was remarkable about the Roxy, in retrospect, is the fact that it ran seven days a week, with three changes of program, and sometimes even double bills. So you had an opportunity to watch between three and maybe five movies every week. If I liked something, I might even go two nights in a row.

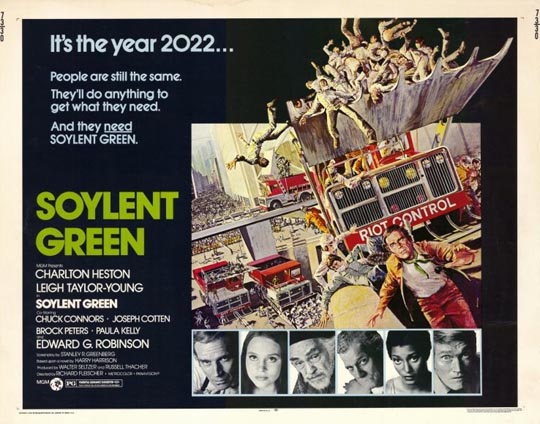

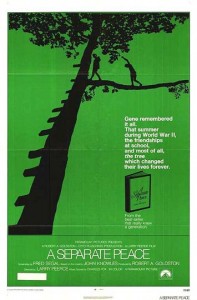

Looking back over my records (yes, I do keep fairly obsessive records), I can see that I watched a pretty odd assortment of movies before I moved to Winnipeg that summer. For instance, there were two by Richard Fleischer – The New Centurions (1972, pretty bad) and Soylent Green (1973, not bad, if you aren’t familiar with the excellent Harry Harrison novel it’s based on, Make Room! Make Room!). I saw Franklin Schaffner’s ponderous, turgid epic Nicholas and Alexandra (1971), and Don Siegel’s Dirty Harry (also 1971; I’d seen that before, of course, but it was worth another viewing). There was Larry Peerce’s tasteful literary adaptation A Separate Peace (1972), and Vincent Price in two of his best: The Abominable Dr. Phibes (1971) and Theatre of Blood (1973). Then there was Sidney Furie’s hackneyed bio-pic Lady Sings the Blues (1972) and Joseph L. Mankiewicz’s stagey version of Anthony Shaffer’s Sleuth (1972).

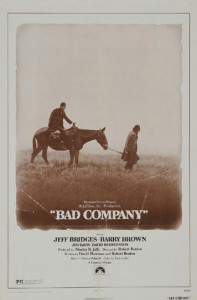

Best of all, perhaps, was Robert Benton’s under-appreciated Bad Company (1972), one of those loose ’70s movies which seemed determined to shake off the rigid rules of Hollywood filmmaking to access something a bit more “real” about the world. Of course, most of those movies were just as concocted as assembly-line studio product, but they were refreshing nonetheless. Bad Company, a picaresque western which co-starred a young Jeff Bridges (clearly indicating the solid career he would go on to have), received mixed reviews at the time (Roger Ebert wasn’t terribly impressed, and even the favourable New York Times notice tempered its praise with comments about sloppiness) and it quietly sank out of sight. It was given a mediocre DVD release in 2003 and you might still be able to find a copy.

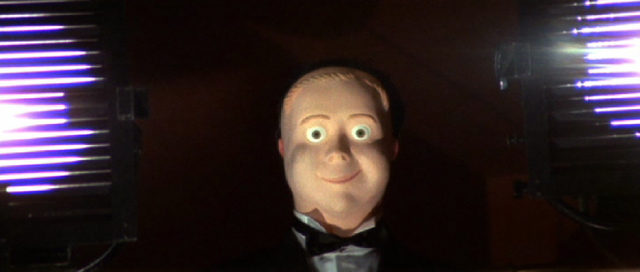

But the oddest thing I encountered at the Roxy that spring was my first Dario Argento movie. I’d read not very favourable reviews of his first two features in Cinefantastique (The Bird With the Crystal Plumage [1970] in issue #1, Cat o’ Nine Tails [1971] in issue #4), both of which approached the films critically with regard to plot – this was before Argento became appreciated for his stylistic abilities rather than his story-telling. When I walked down to the Roxy on a Sunday evening I had no idea what I would get with Four Flies on Grey Velvet (1971), but I already liked the enigmatic title. And as I watched it, I definitely had a sense that this was something new in my experience. There was a dreamlike quality to the narrative (reinforced by the repeated dream/memory sequence of a public execution, possibly somewhere in North Africa, harshly over-exposed in contrast to the generally dark and gloomy look of the film) and the completely wacky, but played-straight idea that the police can photograph a murder victim’s retinas and get an image of the last thing seen before death – in this case, the cryptic arc of four flies against a grey background, which plays well into the climactic revelation of the killer’s identity.

It was the experience of seeing Four Flies at the Roxy that initiated a long-standing appreciation of Argento’s work as well as an addiction to gialli in general, and in my memory this particular film held a key place that anchored that interest and appreciation. But it was four decades before I would see it again (in a very poor German edition from Retrofilm, Vier Fliegen auf Grauem Samt), and a few years later in the much improved 2008 Mya release. But sadly, my rediscovery of the movie after years of watching other Argento films, good and bad, as well as a whole range of other directors’ gialli, was a bit of a disappointment – it’s a clumsy film, and Argento himself seems rather half-hearted in his direction as if dutifully completing his “animal trilogy”.

Still, this new knowledge hasn’t taken away the great memory I have of sitting in the Roxy and getting a glimpse of an irrational world in which narrative logic gave way to something more haunting.

When I moved to Winnipeg soon after that, the very first movie I saw was Claude Chabrol’s Le Boucher – another serial killer story, but this time rooted in a minutely observed social reality and predicated on a very chilling and believable psychological foundation.

Comments