Walter Matthau, man of action?

The series of ten Martin Beck novels written by Swedish husband and wife Per Wahlöö and Maj Sjöwall between 1965 and 1975 are not entirely conventional mysteries. They are police procedurals which focus on the tedious sifting of facts and clues which may or may not lead anywhere, in which accident and coincidence often abruptly alter the course of the narrative, or bring it to an abrupt end without much sense of surprise or revelation, or suddenly transform it into a completely different story which then has to be pursued through more painstaking analysis of evidence. The authors used the series to paint an increasingly critical portrait of Swedish society and politics, and to document the decline of the police into a brutal, almost fascist organization whose purpose shifted steadily from the solving of crimes to the “control” of what the authorities considered an unruly society.

A few months ago, I watched a DVD of Man on the Roof, Bo Widerberg’s 1976 adaptation of the seventh novel, The Abominable Man, a faithful and efficient conversion from page to screen of one of the series’ most straightforward stories. It begins with the brutal murder of a terminally ill police officer in his hospital room; Beck and his colleagues know that the victim, Nyman, was a terrible policeman, violent and corrupt. So they have to dig back into the records and investigate people who had filed formal complaints against him, quickly narrowing the list down to one, a policeman for whose wife’s death Nyman was responsible – and just as they figure out who the murderer is, he takes to the roof of his apartment building in central Stockholm and starts shooting at any policemen he sees down in the streets. While Beck empathizes with the sniper, the police commissioner mounts a disastrous military-style assault on the building.

Watching this movie triggered a renewed interest in the books, the last of which I had read some 35 years ago. It took me a while to dig them out of boxes in the basement, but I eventually found all ten and have just finished reading them in sequence. Gloomy, to be sure, but also engrossing.

It was while reading the fourth book, The Laughing Policeman (1968), that I recalled seeing the American adaptation back in 1973, scripted by Thomas Rickman and directed by Stuart Rosenberg. Rickman had just co-written Kansas City Bomber (1972), the roller derby movie starring Raquel Welch, and would follow Policeman with the script of Philip Kaufman’s The White Dawn (1974) and later, among other things, Coalminer’s Daughter (1980), for which he got an Oscar nomination. Rosenberg, of course, is best known for Cool Hand Luke (1967), The Pope of Greenwich Village (1984) and The Amityville Horror (1979).

The Laughing Policeman is not a very good adaptation of the book – not because it’s been transposed to San Francisco, but because the script strips out all the detail, the ways in which the investigators have to dig back through the identities and backgrounds of the victims of a mass murder on a city bus, leading back to another crime (in the book, committed sixteen years previous; in the film, only two). In the book, Beck has to solve the old cold case in order to understand the motive for the bus murders; in the film, the old case was already his and he had a suspect, but simply couldn’t pin the crime on him. So, very little detecting, all leading to an implausible action finale rather than the book’s sad exposure of pathetic human behaviour.

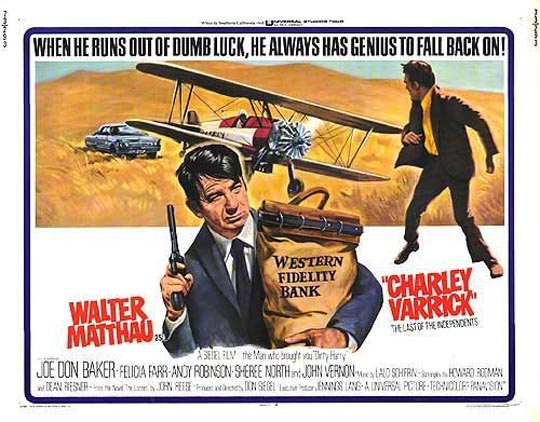

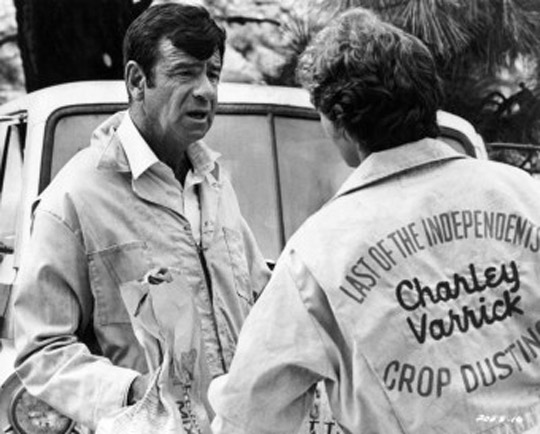

Having tracked down a copy of The Laughing Policeman on DVD, I realized that it marked the centre of an odd two year period in the early ’70s when Walter Matthau briefly became an unexpected lead in thrillers. While he had started out as a dramatic actor in the early ’50s (he delivers a wicked Kissinger impersonation in Sidney Lumet’s Fail Safe [1964]), he switched almost exclusively to comedy after making The Fortune Cookie for Billy Wilder in 1966. But then, in 1973, Don Siegel cast him in Charley Varrick, one of the director’s best features, in which Matthau played a small-time bank robber who inadvertently steals a big stash of mob money and finds himself pursued by both the police and a hit man played by Joe Don Baker. With his loose, shlubby looks, Matthau works well as a guy who’s much smarter than the people around him think he is and he successfully outwits everyone.

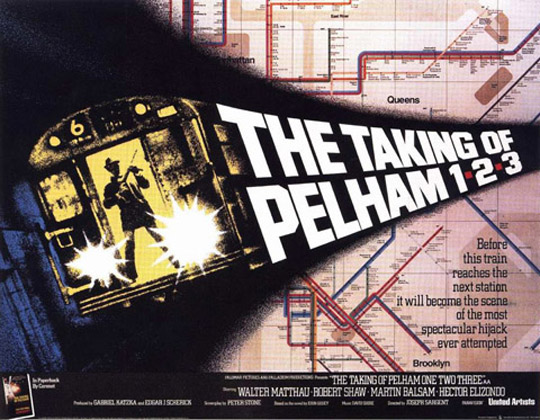

He followed Varrick with Policeman, then the next year capped this run of thrillers with the best of the three, Joseph Sargent’s The Taking of Pelham One Two Three (1974), in which he plays a New York transit employee who has to deal with the hijacking of a subway train (a role Denzel Washington took in Tony Scott’s fine 2009 remake).

Seen together, these three movies illustrate something odd about Matthau as an actor. In Varrick, at tense moments he pops a stick of gum in his mouth and chews with highly exaggerated lip movements. Then in Policeman, the gum completely takes over – the entire performance is built around this bizarre chewing, and frankly I recalled when watching it again that this was the main reason I didn’t like the movie when I saw it back in 1973; it’s an actorly mannerism which is so distracting that you barely notice what else is going on in a scene. But the next year, in Pelham, there isn’t a stick of gum in sight. I wouldn’t go so far as to say that this is the primary reason Pelham is the best of the three films, but it does allow the tension of the plot to do its work without unnecessary distractions. Did Matthau somehow believe that this cud-chewing signalled “drama” rather than “comedy”, finding those sticks of gum a necessary crutch? Did Sargent tell him to get rid of it and just get on with playing the character? Was having to perform the transit cop without the aid of gum the reason that Matthau returned to comedy later that year?

Either way, these three movies offer a peculiar interlude in the middle of a long career: Walter Matthau, almost-an-action-star.

Comments