Year End 2010

I find that my viewing habits in recent years have become so random and eclectic that the idea of coming up with a “year’s best” list is not only difficult – it borders on the arbitrary and meaningless. Much of what I watch these days consists of older films either just caught up with, or re-seen after many years, the balance definitely tipping away from current movies.

So rather than conjure up a random list from the many great, good, maybe-not-so-good-but-definitely-interesting movies I’ve watched this year, I’ll just mention two items. The first simply for the great pleasure I derived from it, the second because, despite some problems, I find it fascinating.

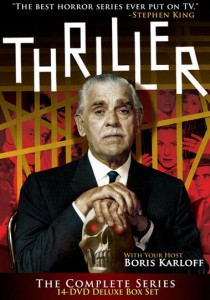

Thriller, with Boris Karloff (1960-62): I used to watch episodes of this anthology series on Saturday afternoons in the late ’60s in Newfoundland. I couldn’t say now how many of the shows I saw back then, and to tell the truth only one really stuck in my mind – the second season’s The Incredible Doktor Markesan. This atmospheric story of a young couple who go to live with the man’s strange reclusive uncle in a run-down house was creepy and disturbing, and it also introduced me to Arkham House, the Wisconsin publisher which kept the legacy of H.P. Lovecraft alive after the author’s death. Markesan was based on a short story by August Derleth and Mark Schorer and I tracked it down in an Arkham House volume of collaborative short stories called Colonel Markesan and Less Pleasant People (which also contains the source story for another episode, The Return of Andrew Bentley). Although I’d occasionally read about Thriller over the years (in Stephen King’s Danse Macabre, for instance, and in other books about classic TV shows), it was really that one episode which kept the series alive for me, and was the reason I’d been on the look-out for it ever since home video arrived on VHS.

So, needless to say, I was quite excited when Image announced their upcoming release of the complete two seasons in one big box set this year. I pre-ordered it, and when it arrived I totally binged; I watched all 67 episodes in less than three weeks. Two things struck me: 1) the overall quality of the series was remarkably high – the episodes were written, directed, photographed and edited like movies rather than studio-bound TV shows; and 2) despite the overwhelming fan consensus that the show only kicked into gear with the introduction of horror and the supernatural with episode 7 (The Purple Room) and that the mystery/suspense episodes were far inferior, I found myself really liking many of the non-horror episodes, and some of them even more than the more highly regarded horror shows.

For instance, Knock Three-One-Two (episode 13), adapted by John Kneubuhl from a Fredric Brown story, stars a young Warren Oates as a serial killer who is unwittingly manipulated by a gambler who wants his wife dead so he can get her money to pay off the gangsters he’s in debt to. This is a tense, beautifully constructed little thriller which could easily have made it as a theatrical noir. And Late Date (episode 27), adapted by Donald S. Sanford from a Cornell Woolrich story, is another tense suspense tale in which Edward Platt (the Chief in Get Smart) kills his cheating wife in a moment of anger; his beefy younger brother decides to protect him by elaborately pinning the death on the wife’s cheesy lover. The details of the plan become excruciating as almost every moment threatens discovery, and then the whole thing is capped off with an effectively ironic ending.

I found that some of the more famous horror episodes don’t actually hold up as well, though no doubt they had much stronger impact at the time they were first aired. Well of Doom (episode 23, directed by the great John Brahm) has a terrifically villainous double act in Henry Daniell (a favourite of the series’ producers) and Richard Kiel (Jaws from a couple of the Bond movies) as demons who kidnap the heir to an estate one foggy night on the moors and torment the young man and his bride-to-be; but in the end the show is let down by a rather prosaic finale. Perhaps the most famous episode of all, Pigeons From Hell (#36), adapted by Kneubuhl from a Robert E. Howard story, and directed by One Step Beyond‘s John Newland, was a big disappointment. Although suitably gloomy with its setting in a decaying mansion on a bayou in which two friends get stranded overnight, with one of them killed by some haunting force, the atmosphere is thick, but the narrative is vague and the significance of the title, hinted at by Karloff in his introduction, never comes into focus. It’s all mood, but unsatisfactory as a piece of storytelling.

With 67 episodes in all, I could go on at tedious length. Suffice it to say that this series, while uneven as any anthology is bound to be, maintained a remarkably high standard and featured work by an impressive array of writers (Donald S. Sanford, who wrote 16 episodes, Robert Bloch, Charles Beaumont, Douglas Heyes, Barre Lyndon) and directors (the prolific Herschell Dougherty, Ida Lupino, John Brahm, Arthur Hiller), and showcased a lot of interesting actors (like a pre-Kirk William Shatner, Warren Oates, Mary Astor, Robert Vaughan, Edward Andrews (in the three best comedy episodes), Constance Ford, and so on). It is generally believed that the show folded after two seasons because it never managed to establish a coherent identity and so couldn’t maintain an audience like The Twilight Zone or Alfred Hitchcock Presents. This may well be true, but seen now in this impressive package (with 27 often informative, though sometimes repetitive, commentary tracks), it is the range and variety of stories that make it a pleasure to revisit.

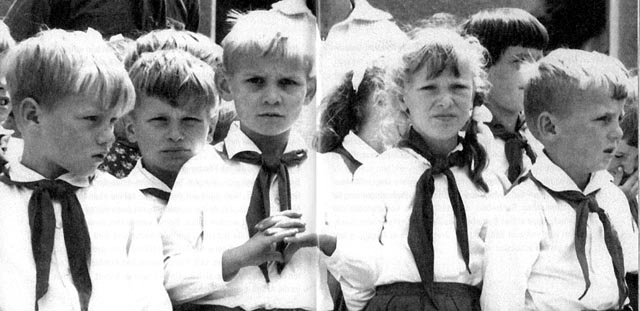

Die Kinder von Golzow (1961-2007) is an 18-disk set from Germany which inevitably evokes comparison with Michael Apted’s 7 Up series. Here, filmmakers Winfried and Barbara Junge began filming the children of a village called Golzow in the Oderbruch region of East Germany on their first day of school in 1961 and then kept returning to them for the next 40+ years. The project was less structured and systematic than Apted’s series, with six short films covering the first 15 years, then expanding with longer works a few years after that. The approach taken by the Junges is also quite different from Apted’s: the 7 Up films are deeply concerned with the ways in which class and social structure shape individual lives and its method is to allow its subjects to speak and comment on their own lives and development. The Golzow series, on the other hand, at least in the early years, is concerned to show the great advantages of living in a controlled, socialist society and we barely hear the children speak at all as the omnipresent narrator continually comments on their lives and development. Apted observes his subjects as they differentiate themselves; the Junges work hard to homogenize theirs.

But then in 1980, with Lebenslaufe, a four-and-half hour collection of “biographies”, the series suddenly opens up. The Junges take all the previous material plus newly shot segments of their now mid-20s subjects to construct ten individual portraits, ranging from about ten minutes to half-an-hour each, and we get to hear their voices and their thoughts on their lives. Some are achieving the aims they set for themselves back at school, others are in jobs which no longer interest them; a number are parents struggling to raise families (either in couples or alone) in a system which makes it difficult to earn sufficient money to have a place of their own.

The series was obviously conceived with propagandistic intentions (but then, in a sense, 7 Up is propaganda too, with its slightly left-leaning determination to dissect the British class structure), and while those intentions impose limits which can be frustrating for the viewer, it nonetheless provides glimpses of everyday life in what we now know was one of the most heavily policed and repressive of the communist dictatorships. To date, I have actually only watched the first ten of the total 43 hours, and that comprises all the episodes made before the fall of the Berlin Wall and the reunification of Germany. It’ll be interesting to see how the Junges’ approach changes and adapts once the social system is irrevocably changed by the collapse of the socialist state. I’ll write about the series again once I’ve tackled the remaining thirty hours.

Comments