DVD of the Week: All White in Barking/Men of the City

I envy Marc Isaacs. Not just because he’s one of the best documentary filmmakers now working in Britain (or anywhere, for that matter), but because he’s found a sympathetic producer in Nick Fraser of the BBC who understands what Isaacs is doing and encourages and supports him in his work. After the past few years working at the National Film Board, where it has become ever more difficult even for filmmakers with a great deal of experience and good track records to get projects programmed – where the programming committees keep sending proposals back to be reworked and reworked again in some strange effort to see the finished product on paper before it’s ever actually approved – I can’t help but be jealous of the trust Fraser places in Isaacs to take an idea and follow it wherever it leads, knowing that something worthwhile will emerge.

I guess I have a very particular concept of the ideal documentary. It seems to me that the essence of documentary is curiosity about the world, the urge to explore and return to share what you’ve learned with others. I dislike a lot of what passes for documentary on TV (I spent two years cutting a weekly “documentary” series), where a script is often written before shooting starts and then material gathered to fit what’s already been written. Making a documentary should be a process of uncovering, of learning – the kind of thing David and Albert Maysles did for decades: the filmmaker finds a subject that interests him or her and then begins to shoot, following wherever the subject leads, then constructing an illuminating narrative out of the material that’s been gathered. Of course, this is not the “neutral” process that television news and magazine shows like 60 Minutes pretend to be; in the hands of a talented filmmaker, it’s as artful and creative as any other kind of filmmaking. True documentaries are “written” in the editing, not scripted beforehand. The documentaries I’ve edited for John Paskievich have been made this way – we start with over a hundred hours of material that John has shot which we then sift through until we find what interests us most about the people and situations he’s been following and then construct what we feel illuminates those characters and situations as honestly and faithfully as we can.

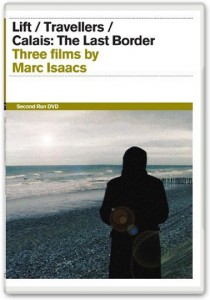

This is the process Marc Isaacs uses in his remarkable films. His first documentary, Lift (2001), is startlingly original and brilliant in its simplicity. He had been working on a feature which was using a flat in a residential highrise as a location, and day after day he had to ride the elevator up to the set and down again, experiencing those transient moments in which one shares a small space with strangers, people who after a time become familiar though still unknown. So after the feature wrapped, Isaacs went back to that building and spent several months riding that elevator with a video camera. Gradually, the people he sees over and over again get used to his presence and they begin to interact with him, exchanging casual remarks, offering bits of personal history, sometimes imparting confidences, offering food – one woman brings him a small religious icon to pin to the wall to keep him company. And so, gradually, we start to glimpse the lives of the building’s residents, a mix of the old, the young, natives and immigrants, and get a flavour of the daily life of this vertical community.

Isaacs followed this by expanding his canvas and his “location” with Travellers (2003), taking his camera into a railway station and riding the trains. He approaches people and some of them are surprisingly receptive, opening up to him, talking about their lives to this stranger who by sheer persistence becomes familiar to them as they see him day after day. But of course, not everyone with a camera would evoke the responses Isaacs gets from his subjects; the key is his personality, which comes across in each film, quiet, pleasant, endlessly and sympathetically interested in other people.

Isaacs has continued to expand his canvas since he started making documentaries in 2001. His two most recent films, released on DVD by Second Run as a follow-up to their release of his first three films two years ago, show him building on his strengths while also stretching the boundaries of his chosen technique. In both All White in Barking (2007) and Men of the City (2009), he moves out of the public spaces of his previous films and begins to penetrate the private spaces of his subjects; and in Men of the City he is beginning to apply more overt editorial techniques which comment on the material in ways he has previously avoided … but even here, that commentary isn’t as simple and obvious as it seems at first.

Barking is a suburb east of London which in recent years has changed radically as the original residents have moved away and the population has become a multi-cultural mix of immigrants. Isaacs begins his film by talking to a handful of the remaining white residents, letting them express their prejudices – most of which seem completely unexamined, couched repeatedly in terms of “it’s just best to be among your own”. These are not rabidly racist people, most of them more concerned about the disappearance of the community they grew up in than particularly hostile to the new community – or rather collection of communities – which now surrounds them.

There’s Dave, the man who goes out campaigning for the far right British National Party (whose candidates received 10,000 votes in Barking in a recent election), but who turns out to have an adored grandson whose father is Nigerian (now separated from the daughter), and whose other daughter is dating a mixed-race man (one of the best moments of humour comes when Isaacs points out that fact, and Dave is surprised and disbelieving, not having noticed that the boyfriend isn’t completely white). There are the middle aged couple, Sue and her husband Jeff, who view Dickson and his family, the African neighbours across the street, with some suspicion; Isaacs persuades them to go over there for dinner one evening. Before the visit, they speculate nervously about what kind of food they’ll be given because, you know, their tastes are “different”. They discover that these neighbours are warm and friendly hosts, very religious, and that the food, though a bit unfamiliar, is perfectly edible. Then there’s Steve and Valerie, who have owned a butcher shop in the high street for a long time, but have seen business decline because the new residents aren’t interested in those English cuts of meat and frequent the more “ethnic” butchers who have opened up in competition.

But beyond these people, Isaacs has found others who reflect a more complex social situation. There’s Monty, an elderly Holocaust survivor who befriended Betty, an African woman, in his shop and now lives with her as his caretaker. She has a family back in Africa and hopes one day to take Monty there to meet them; meanwhile, he takes her to a reunion of camp survivors, where some people seem surprised, others envious. When Sue and Jeff have a backyard barbecue, inviting the African neighbours from across the street, they also invite the Albanian man from next door, who seems to have no problem with anyone – until he’s asked if he’d want his daughter to marry a Serb, at which point he expresses an emphatic antipathy.

What emerges from All White in Barking is a complex, nuanced portrait of these people who turn out to be confused, contradictory, often unthinking, and – when seen apart from heated political rhetoric and stereotyping – merely human.

*

This is also, ultimately, what we take away from Men of the City, which initially looks as if it will be rather schematic, making easy points. The City of the title is London’s financial district, and the title immediately evokes images of suit-wearing, briefcase-carrying businessmen immersed in the arcana of international finance. But Isaacs begins with a street cleaner sweeping out the gutters at dawn. While this disrupts that initial perception of the place, it also suggests a perhaps too east dichotomy – the great British idea of class difference, with those at the bottom remaining invisible and insignificant. But it turns out that this lowly labourer is an intelligent, educated, well-read man who enjoys what he’s doing, contributing something socially useful while having plenty of time to think about what matters in life.

Isaacs also introduces us to a struggling Bengali immigrant who makes a bit of money by sitting on a sidewalk for ten hours a day holding a sign advertising a nearby Subway sandwich shop, while single-handedly raising a teenage daughter who, much to his frustration, is growing up like an English kid rather than a Bengali. This man loses his job because he has to take time out to visit his daughter in hospital and in this job climate there’s no room for personal business.

In contrast to these two men we see two figures from the business world: a hedge fund manager who is seemingly never away from a computer screen, even when relaxing with his weekend hobby of photography at his luxuriously modern house by the sea. He also has kids, but his wife has left with them because he never had time for them. Now they visit and everyone is friendly, but he can’t not work. Then there’s the man who has worked for 30 years at a financial company because his factory-worker father insisted that he pursue an easier life than the one on the assembly line; but now, having spent decades in this other stressful work environment, he is in the process of leaving to form his own company, to freelance, and is almost overwhelmed with fears of insecurity.

Again, the dichotomies here – the happy street cleaner, the businessmen driven by fear and insecurity – might seem too pat, if it weren’t for the fact that Isaacs insinuates himself so deeply into their particular separate worlds; all of them emerge as fellow human beings driven by needs and emotions we can recognize as our own. He achieves this by taking the time to listen, and by showing respect for the people he’s filming. Some might think that what he does is not “proper” documentary – he interacts with his subjects, he arranges situations for them (the dinner with the neighbours), but not in a manipulative way. He sets something in motion and then observes what happens and, quite miraculously, we see how easy some things can be shifted and that people we might have condescendingly dismissed are capable of change and growth.

The art of Marc Isaacs resides in this ability to make visible what we might normally not see and to penetrate preconceived prejudices and bring out the humanity his subjects share with each other and with us, the audience.

Comments