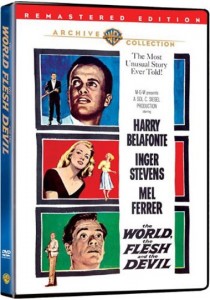

DVD of the Week: The World, the Flesh & the Devil (1959)

Many of us who live in relative urban comfort enjoy experiencing a vicarious struggle for survival through books and movies. This goes back at least as far as 1719 and Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe (how many times has that been filmed?). Crusoe, like many wilderness narratives, focuses on an individual separated from society, having to survive by his wits in an often harsh, inhospitable natural environment. Cut off from group supports, these loners have only their own skills to rely on.

Towards the end of the 19th Century, when it seemed that so much of the world had been explored and “tamed”, a new variant began to appear – the first significant instance might have been Richard Jeffries’ After London in 1885 (with the all-but-forgotten yet aptly titled Mary Shelley novel, The Last Man [1826] as a precursor). In this narrative, instead of the individual being lifted out of society, society itself is obliterated, leaving a survivor, or at best a handful of survivors, to fend for themselves in a new and lonely world.

This was the subject of M.P. Shiel‘s 1901 novel The Purple Cloud, which in the most tenuous of ways apparently served as the original source for Ranald MacDougall’s The World, the Flesh & the Devil (1959); there’s a credit way down in the opening titles below “Process Lenses by PANAVISION” that reads “Suggested by a Story by Matthew Phipps Shiel”. In The Purple Cloud, a polar explorer unwittingly unleashes God’s vengeful wrath in the form of a poisonous cloud which covers the globe and kills off literally everyone. The explorer spends the next twenty years roaming the world, burning cities to the ground for amusement, and single-handedly building a huge palace. Eventually, he meets a 20-year old woman who has lived only in this empty world and is thus completely untainted by humanity’s failings. Initially he rejects her, but eventually accepts her … at which point all remnants of the cloud disappear from the Earth.

This kind of narrative became quite popular in mid-century, with R.C. Sherrif’s The Cataclysm, the novels of John Wyndham (The Day of the Triffids, The Chrysalids, The Kraken Wakes) and John Christopher (The Death of Grass aka No Blade of Grass — and where’s the DVD of Cornel Wilde’s 1970 adaptation of that? — Update: it eventually came out as a Warner Archive release, which looks pretty good after an initial serious mastering error.), and so on, with a distinct subset predicated on global plagues: Richard Matheson’s I Am Legend (a plague story conflated with a vampire tale) and Terry Nation’s great 1975-77 BBC series Survivors. Then of course, after the Second World War, the primary device for these narratives became the atomic and hydrogen bombs – not surprisingly, as for the first time in history it seemed actually feasible for civilization to be brought to an abrupt end.

Works like Survivors and the novels of Wyndham at least have a gloss of plausibility underlying the survival fantasy – they posit scattered individuals and groups struggling to rebuild some kind of social order in the ruins. But there’s another subset in this genre, what you could call the “last man” narrative. Here, literally, we seem to find a single, lone individual who has somehow managed to escape the fate suffered by everyone else. Eventually, mostly for dramatic purposes, this individual will encounter one or two other survivors, but for the most part the underlying narrative is about what the individual does in an empty world – Robinson Crusoe with a whole planet instead of an island (of course, even Defoe found it necessary to introduce a second character after a while, as a man alone against nature offers diminishing dramatic returns as the story goes on).

Arch Oboler’s Five was the first full-blown movie iteration of this narrative, but for one of its purest expressions, we can now savour MacDougall’s The World, the Flesh & the Devil in a nicely restored DVD version from the Warner Archive (the widescreen black-and-white image is beautifully crisp, though at times it feels a little too cramped vertically, with insufficient headroom). The structure of this movie (borrowed by such subsequent films as Geoff Murphy’s The Quiet Earth) gives us the first third with a lone protagonist who somehow survives the cataclysm; then he unexpectedly meets a woman and, after a bit of uncertainty, a relationship of some kind begins to form; then a second man appears and suddenly there’s competition. It’s quite obvious then that by its very nature, this narrative is allegorical (a point reinforced by the fact that just days after everyone on the planet has died from radiation poisoning, there are no bodies anywhere) – so a little puzzling that many who have commented on MacDougall’s movie use that term almost as an accusation of defect. Both John Baxter in Science Fiction In the Cinema (Paperback Library: New York, 1970) and Phil Hardy in the Aurum Film Encyclopedia: Science Fiction (Aurum Press: London, 1984/1991) use the term “blunt allegory”. This seems a bit like referring to a Sherlock Holmes story as a “blatant mystery”.

One interesting aspect of these narratives, established in Five, taken up in MacDougall’s movie, reappearing in Kinji Fukasaku’s global plague epic Virus (1980), is the fact that male survivors generally outnumber female, giving rise to sexual conflicts (the implication apparently being that women wouldn’t have the same kind of conflicts if they outnumbered men). Dr. Strangelove (1964) even addressed this issue directly with the mad scientist’s proposal that the shelters be stocked with ten young and attractive women for every man.

I first read about The World, the Flesh & the Devil in John Baxter’s book forty years ago but, until now, never had an opportunity to see it. That makes for an awful lot of expectations to fulfill and I’m happy to report that I wasn’t disappointed. But I was a bit surprised that for all those years I carried mistaken ideas about the film based on comments by many of the critics I’d read. But first – the film itself.

Harry Belafonte plays Ralph Burton, a mining engineer who is trapped by a cave-in which happens to coincide with the release of a powerful but short-lived radioactive cloud which kills everyone in a matter of days, but then dissipates by the time he digs himself out. At first puzzled, then a bit deranged, he makes his way to New York City and sets about restoring some semblance of pre-catastrophe life by rigging an apartment building with electricity, rescuing books from the decaying library, and making daily calls on a shortwave radio in hopes of discovering other survivors. Belafonte gives a terrific performance, expressing the character’s inner strength as he fights against the horror and loneliness of his circumstances.

Half an hour in, we discover that he’s being watched by a woman, Sarah Crandall, who seems too fearful at first to reveal herself. But they do eventually meet and he extends electricity and, in time, even a phone line to her own nearby building. There’s tension in the relationship developing between them (for reasons to be discussed below), and then after another half hour our third character shows up, almost dead, piloting a boat into the harbour. This is Benson Thacker, who’s been at sea for a long time and has seen no other living people until he meets Burton and Sarah.

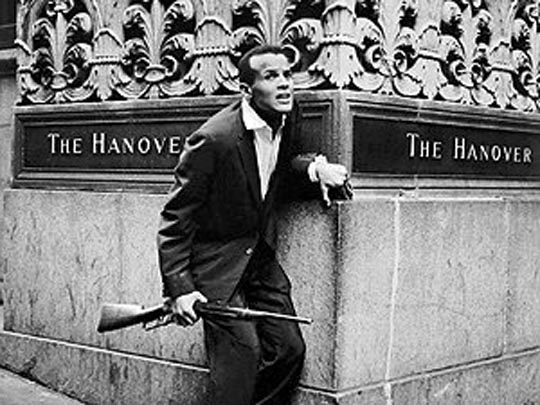

The film’s final act centres on the growing conflict between the two men with regard to who gets the woman, leading to a showdown with rifles in the empty canyon streets of the city.

The first thing that struck me was just how well MacDougall sets up his world. The scenes in the mine with Burton alone, waiting to be rescued, then finally digging himself out, serve to establish the character as smart, capable, self-possessed, and very likeable. Then after he reaches the surface, the empty world is brilliantly created. This, of course, was long before CG made it relatively easy to show a deserted metropolis; MacDougall had to shoot it for real, and the vision of an empty New York is often breathtaking, both beautiful and chilling … the shots of Burton pulling his kid’s wagon of supplies down long empty streets are more powerful than anything in, say, the Will Smith I Am Legend. There’s a quietly moving moment when Burton enters a church, looks up at the altar, then gestures mutely towards the emptiness outside as if asking God what the hell happened. (This was embellished in The Quiet Earth with lone survivor Bruno Lawrence bursting into a church armed with a shotgun, which he aims at the figure of Christ on the cross, demanding answers from God “or the kid gets it!”)

The second thing to notice is just how good the three performances are, and how well they mesh with each other. This is a very well-directed film, both visually and dramatically.

The third thing: just how wrong most of what I had read about The World, the Flesh & the Devil had been. As almost everyone has said, this movie is an “allegory about race”. But the way it has been interpreted seems to have nothing to do with what’s actually on screen … and that misinterpretation is behind those accusations of it being “blunt” or “crude”.

Yes, of course there are racial issues. It was made in 1959, it starred Harry Belafonte and placed him opposite a charming blonde (Inger Stevens), and set him in conflict with a suave white man (Mel Ferrer). But I can’t understand how Hardy in the Aurum volume can say “Ferrer … when he comes across Belafonte & Stevens, is horrified by their union”, when we clearly see that he’s relieved to have found them and is grateful for Burton saving his life, and even says and shows quite clearly that he likes the other man. He also considerately questions Sarah about the status of her relationship with Burton before actively beginning to pursue her. The conflict that arises between them is firmly rooted in sexual competition, not racism.

In fact, somewhat strangely, it’s Burton who seems to have the racial hang-up. He is almost crippled by what he experienced in the prejudiced world before the catastrophe. The more Sarah shows her growing affection for him, the more his bitterness rises to the surface, and despite obviously returning her affection, he becomes more and more hurtful towards her because, as he says at one point, in the previous world she wouldn’t even have noticed him. There are valid psychological reasons for his at times irrational behaviour towards her, but on another level, it can be read as an expression of frustration because, in the real world of 1959, Hollywood rules simply wouldn’t allow a black man and a white woman to have a romantic relationship.

So, if there is an allegory of race here, it’s actually about the effects of racial oppression internalized by the victim, the ways in which this deforms the ability to form human, emotional relationships, and can even interfere with the immediate needs of personal survival. Burton brings home a couple of department store mannequins (dubbed Betsy and Snodgrass, both white, not surprisingly) for company. (This device is hinted at in The Omega Man, but Charlton Heston is only permitted to look longingly at the swimsuit display, not actually take the dummy home; and in I Am Legend, Will Smith keeps the unsavoury sexual implications at bay by limiting his dummy interactions to a music store.) But even in the fantasy Burton creates with his two companions, he restricts the relationship; the mannequins are a couple, and he is merely their host (though he does go so far as to tell “Betsy” that she’s “too good for Snodgrass”). In the end, he can no longer stand the condescending superiority of the perpetually grinning Snodgrass and he tosses the dummy off the balcony – but of course, all of Snodgrass’s contempt is actually a projection of Burton’s own feelings. Significantly, it’s his angry rejection of that contempt that finally initiates the meeting with Sarah and the opening of a new possibility, as she reveals herself because she believes that Burton has thrown himself from the balcony. But he still has a lot of anger to overcome.

When Thacker shows up, this conflict inside Burton is amplified – he all but pushes Sarah onto the “more suitable” white man, while at the same time ramping up the conflict with Thacker. Everything he’s brought with him from the old world tells him that there can only be one valid pairing, but a part of him just doesn’t want to let her go – and Thacker realizes that the only way to resolve the situation is for one of them to be eliminated … which leads to the armed showdown.

The film reaches its allegorical peak towards the end when Burton reads the Biblical passage on the monument in front of the United Nations building about turning swords into ploughshares and studying war no more (strangely, Baxter attributes this scene to Ferrer rather than Belafonte; but then, he also invents a completely non-existent scene for Burton and Sarah’s first meeting). Burton throws down his gun and confronts Thacker, refusing to put up a fight. Faced with this lack of resistance, Thacker also loses his will to fight. Sarah joins them and, as Baxter puts it, “In a final shot, the three walk off arm in arm and two cherished ideals of western society – monogamy and racial purity – disappear …” Obviously, this ending completely contradicts what appears to be a critical consensus about the Ferrer character: it can only make sense if Thacker is not an “obligatory rotten apple” as Baxter calls him or “a bigoted adventurer” as Hardy puts it, but rather is just another ordinary person like the other two… In fact, I suspect that Baxter makes his error about who reads the words on the monument because he somehow needs to perceive a radical change in the supposedly racist Thacker before there can be a possibility of that harmonious ending.

It seems to me that The World, the Flesh & the Devil is a far more nuanced film than it’s been given credit for, and certainly on a visual level it’s one of the most striking and enjoyable “last man” survivor tales ever put on film.

Comments

Excellent review of a film I watched when I was 18 years old. I had forgotten the title. I only remembered the word Snodgrass. With this word and science fiction movie, I found your nice review.

Congratulations!

Hi Miguel. I’m glad you found it! I’ve seen so many movies over the years that my head is stuffed with scenes and images that I can no longer recall the source of. It’s always nice when one of those memories gets resolved like this.

I found your article today, March 15, 2019, while looking for info on some of the buildings and backgrounds used in this movie. I am still looking. This movie was ahead of it’s time in 1959 but is overkill for today, and too slow as is for a theater. The movie Five was somehow better, even though this one is still good. Those who don’t get The Twilight Zone won’t understand.

Lovely review. I watched this film in 1963 when I was 14 years old, and again yesterday at age 70. I was a little afraid to see it again— it had a big impact on me as a teenager. It seemed weird and VERY adult. I barely understood the sexual tension although the racial tension was so clear and so relevant to the times.

I understand your trepidation – I’m always nervous about seeing something that had an impact on me when I was young. But I think on average, the disappointments are far fewer than the confirmations of those memories.