Ealing Studios

I recently got to see the final film produced by Ealing Studios, The Siege of Pinchgut (1959), a tense hostage drama made far from the cozy English countryside and villages the studio is often associated with. Directed and co-written by Harry Watt, starring an American (Aldo Ray) and shot on location in Australia, it seems like an odd conclusion to the history of a company best known for its very British comedies.

I couldn’t say when I saw my first Ealing movie, but it seems as if I grew up with those famous comedies, a number of which I’ve seen many times over the years. The cream of Ealing’s comedy crop certainly deserve their reputations as classics – Alexander Mackendrick‘s Whiskey Galore, The Man in the White Suit and The Ladykillers, Robert Hamer‘s Kind Hearts and Coronets, Charles Crichton‘s The Lavender Hill Mob. But what I’ve discovered in the past few years, as more of Ealing’s movies have become available on DVD, is that some of their comedies are rather pokey and parochial — “little England” stories like The Titfield Thunderbolt and Passport to Pimlico are cramped celebrations of a rather phony quaint Englishness which now seems uncomfortably dated. Strangely, it was these kind of films which gave Ealing its overall reputation for quite a long time as a cautious, conservative, “safe” company, with the rather dark tone of some of Mackendrick’s films and Hamer’s serial-killer comedy apparently an anomaly.

The studio itself was built in the early ’30s by people who had been in film production since the beginning of the century and it serviced dozens of productions before the arrival of Michael Balcon in 1937 and the initiation of Ealing as a production company in its own right. Balcon then presided over the company for the rest of its life, his personality and outlook defining the Ealing style and attitude. As the brief history of the studio on the now-defunct Britmovie site put it: “It was Balcon’s mission to present the British character, or his idea of it. He regarded the British as individualists who were not averse to joining up with each other to battle against a common cause. He saw a nation tolerant of harmless eccentricities, but determinedly opposed to anti-social behaviour. He venerated initiative and spirit, personal achievement rather than reliance on some higher authority. He was of the ‘small is beautiful’ persuasion, not caring for large organisations or the bureaucratic powers of civil servants. Ealing’s values were decent, virtuous and simplistic, and finite of ambition.”

The big surprise for me has been discovering just how wide a range of genres Ealing produced in its two-decade history, before shutting down production in 1959, and how the studio’s output contained that English cosiness alongside a grittier, more realistic view of the country. Right now, of the 26 Ealing films I have on DVD, only seven are comedies; the rest are war films, crime stories and realist dramas.

Even the war films indicate that the company’s reputation for cosiness and conservatism is too limited. While there are solid propaganda movies designed to rally the audience to the cause, urging everyone to pull together – movies like Harry Watts’ desert warfare tale Nine Men (1943); Charles Frend’s gripping San Demetrio, London (1943), about the crew of a torpedoed tanker sticking with their ship and bringing it to port; Charles Crichton’s For Those In Peril (1944), about the efforts of air-sea rescue crews risking death to retrieve downed RAF crews from the English Channel – Ealing also produced two of the darkest movies of the war years (both 1942): Thorold Dickinson‘s The Next of Kin, a warning of the consequences of civilians and military personnel inadvertently giving fragments of information to enemy agents, resulting in a disastrous raid on the French coast, which was released just two months before the disastrous raid on Dieppe which cost more than 6000, mostly Canadian, lives; and Alberto Cavalcanti‘s Went the Day Well?, the story of a small English village which is taken over by German paratroopers disguised as British soldiers. The gradual realization of the locals and the ways in which they deal with the situation reveal conflicting attitudes on the Home Front, and eventually leads to acts of violence which still seem shocking.

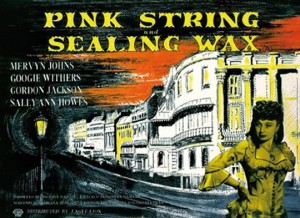

Before the two great Ealing comedies of murder, Robert Hamer’s Kind Hearts and Coronets (1949) and Alexander Mackendrick’s The Ladykillers (1955), there were two other bleak, non-comedic movies about crime and murder, both directed and co-written by Hamer: Pink String and Sealing Wax (1945 – the same year that Hamer contributed to Ealing’s classic horror omnibus, Dead of Night) is a Victorian drama about a grimly righteous chemist who discovers that his own son is implicated in a sordid lower middle-class murder, while It Always Rains on Sunday (1947) has a kind of “kitchen sink” realism, telling the story of a woman who has married into an East End family, resented by her husband’s grown daughters, who suddenly finds herself hiding a former fiance who has just escaped from prison. Both films are built around superb performances by Googie Withers.

Basil Dearden‘s The Blue Lamp (1950) and Pool of London (1951) combined the documentary techniques introduced at the studio by Cavalcanti with post-war social concerns and a touch of melodrama. The Blue Lamp presents the traditional rather warmly sentimental view of the English “bobby” on the beat running smack up against violent, nihilistic post-war youth. Despite the fact that Jack Warner’s avuncular P.C. Dixon is gunned down by young hoodlum Tom Riley (Dirk Bogarde), he was miraculously resurrected for the long-running BBC series Dixon of Dock Green (1955-76). Dearden made equally good use of real London locations for Pool of London, the story of two sailors with a couple of days ashore while their ship takes on cargo at the London docks; they get involved with a couple of women, which is fine, but also with a gang of criminals, which isn’t so good. The mix of documentary locations and melodramatic storylines in these films doesn’t always gel, but the images of post-war England remain fascinating.

In 1952, the company released both Thorold Dickinson’s Secret People, a melancholy depiction of ordinary lives disrupted by political violence, and Mackendrick’s Mandy. Mackendrick displays his amazing skill with children in this compelling, intense story of a little girl born deaf and initially sheltered by her family; when the mother reaches out to get help all kinds of hidden feelings and motives are triggered, the girl’s welfare almost buried by adult fear, shame, ego and anger.

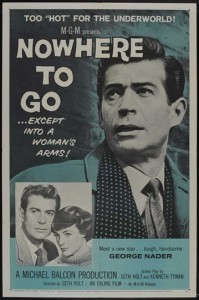

Charles Frend‘s The Long Arm (1956) offers an interesting contrast with The Blue Lamp; in just a few short years the romance of the British policeman has evaporated – as Jack Hawkins’ Superintendent Tom Haliday tracks down a murderous safe-cracker, the job takes an enormous toll on his personal life and ultimately leads to a pointless sacrifice. And just two years later, Seth Holt‘s Nowhere To Go (1958) offered one of the bleakest British noirs ever. A thief, having stashed his loot in a safe place, willingly goes to jail with the intention of enjoying the spoils when he gets out – but he’s given a far longer sentence than expected and decides to break out. Things go steadily more wrong and after he inadvertently kills a former accomplice, no one is willing to help him … that is until he meets a young socialite (Maggie Smith in her debut), who gets him out into the country. But by then he doesn’t trust anyone, and finally he dies wrongly believing that the woman has betrayed him.

So, given this record, that final production, The Siege of Pinchgut, doesn’t seem quite so surprising after all. Ealing had previously produced films in Australia (notably the World War Two “western”, The Overlanders [Harry Watt, 1946], about a massive cattle drive across the barren North to remove the animals from possible capture by the Japanese), and stories of crime were familiar to the company. In Pinchgut, Aldo Ray plays Matt Kirk, a criminal who has since gone straight, but whom the police have railroaded for a crime he didn’t actually commit. His younger brother Johnny recruits a couple of hoods to help break Kirk out; the con only wants to be given a new, fair trial. A series of circumstances get the group trapped on a small island in Sydney Harbour, where they take the caretaker and his family hostage while Kirk sets out his demands. When the authorities are reluctant to cooperate, the situation escalates, shots are fired, and Kirk threatens to fire the island’s cannon at a ship in the harbour which is carrying explosives – a threat which would level a large part of the city if carried out. As Johnny falls for the caretaker’s daughter and the other hoods become more desperate, Kirk descends into a megalomaniacal obsession where his need to prove his innocence turns him into a kind of monster.

The Siege of Pinchgut is a solid piece of entertainment, made with Watts’ typical documentary-inflected skill, and while it doesn’t attain the stature of Ealing’s best films, it’s not a bad way for the company to wrap up its history.

Comments

I was very young when I first started to watch Ealing Studios film work. Household fun, acted by great actors and actresses which we don’t have today. I was born in 1940 a seemingly long time ago, Will Hay was one of my first films, then came others with the Gainsborough lady leading the way. The audiance would applaud after the film and pay respect to the Monach and stand when the anthem was played at the end of the film, nothing like it today, a touch disrespectful I feel. Whatever the film Ealing made was, for myself, a winner. Good humour, no bad language and, of course, the scenery was totally unspoiled. The one thing I reckoned with is that I was never bored not like todays blockbusters of today, the big buck movies from over the pond. Why can’t we have these films remade for the little screen????

One rather important distinction in reviewing “San Demetrio 1943” It was NOT torpedoed by the Scheer. It was shelled and set on fire by those shells – the Scheer stood too far away for torpedoes. If you care to add in how the “Jervis Bay” (protecting that convoy) died – it was shelled also by the Scheer until sunk.

I stand corrected.