DVD of the week: Messiah of Evil (1973)

Messiah of Evil (1973) is one of those movies I’d vaguely heard about over the years, but never had an opportunity to see until the recent DVD release from Code Red. In fact, it seemed that I’d only heard about it at all because it was made by Willard Huyck and Gloria Katz, who had worked on a number of projects with George Lucas – co-writing American Graffiti and Indiana Jones & the Temple of Doom, not to mention perpetrating Howard the Duck. As Huyck and Katz explain in the extras on the disk, Messiah of Evil was made as a deliberate career move. But it seems a more interesting movie than mere commercial calculation would indicate and, seen in the context of the time it was made, I think it shows a promise which Huyck and Katz never really delivered on in their subsequent work.

As with most areas of North American life in the ’60s, the movie industry went through some big upheavals. The decline of the studios after they were forced to give up their own exhibition divisions in the ’50s meant that the previously tight controls exerted over production began to loosen just as large parts of the audience were shifting their attention to television. In the late ’50s, the shift towards serving a more youthful audience boosted production of what were considered more disreputable genres – sci-fi, horror, juvenile delinquency – which permitted producers to make more money on smaller investments. This gave rise to an increase in “disreputable” content – crime, violence, sex – which undermined the hegemony of the Production Code which had essentially instilled a culture of self-censorship within the studios since the early ’30s.

As the Vietnam War produced greater social upheavals – the increasingly confrontational anti-war movement in parallel with hippies and the love generation – that disreputable content edged its way into mainstream movie-making; the appearance of Bonnie and Clyde, The Wild Bunch and Easy Rider in the late ’60s virtually caused the collapse of much of what Hollywood had traditionally stood for. Depending on one’s point of view at the time, this either opened a door to whole new possibilities or it opened a pit into which popular culture was irretrievably disappearing.

The late ’60s and early ’70s were a remarkable time in American filmmaking because that opening allowed a whole new generation to emerge without requiring them to conform to studio politics – Coppola, Scorsese, Rafelson, Bogdanovich, Demme et al. – while at the same time the influence of European filmmaking, particularly the French nouvelle vague, offered stylistic alternatives to the classic Hollywood model. The new Criterion box set America: Lost & Found (a complete collection of the movies produced by innovative BBS Productions) points to the genesis of the “independent movie”, while other, already established directors like Arthur Penn and Sam Peckinpah took the opportunity to go places that would have been forbidden before; both Bonnie and Clyde and The Wild Bunch were financed by Warner Brothers, one of the first studios to take the plunge. Of course, that kind of freedom couldn’t last forever and by the mid-’70s the remnants of the studios were being absorbed by huge media corporations which in some ways were far more restrictive in what they were willing to produce, gearing the mainstream in the wake of Jaws and Star Wars towards an endless supply of genre-based and increasingly formulaic blockbusters aimed at younger audiences.

Perhaps it’s not too surprising that many of the major filmmakers who emerged at that time got their start with Roger Corman, who himself had appeared on the fringes of studio filmmaking in the ’50s, almost single-handedly setting the standard for low-budget, youth-oriented exploitation. He understood the market and he was very savvy when it came to tailoring content to budget with an eye to maximizing profits. The Corman model of exploitation offered an example to other filmmakers and in the early ’70s there was a boom in low-budget, often regional, production of horror movies which ranged from smart exploitation – William Crain’s Blacula (1972), Bob Kelljan’s Count Yorga, Vampire (1970), Ray Danton’s Deathmaster (1972) and Psychic Killer (1975) and Michel Levesque’s Werewolves on Wheels (1971) – to something a bit stranger, more unexpected.

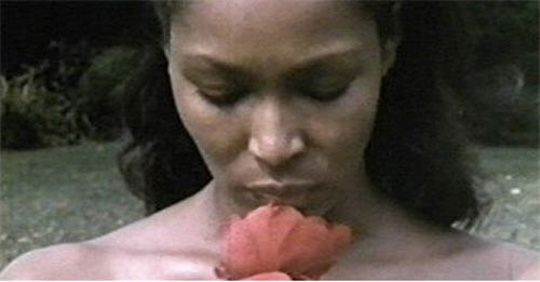

In the early ’70s, there appeared a number of odd, one-of-a-kind horror/fantasy movies which were made with something more than crass exploitation in mind. In their way, these movies exhibit a creative sensibility which could justifiably be called artistic. There was Bill Gunn’s Ganja & Hess (1973), which used elements of the vampire film to explore questions of black identity in a turbulent contemporary America; Richard Blackburn’s Lemora: A Child’s Tale of the Supernatural (1973), which also used vampiric elements, this time to explore a young girl’s sexual awakening (there are echoes of Jaromil Jires’ masterpiece Valerie and Her Week of Wonders [1970] in Blackburn’s movie, though I have no idea whether he ever saw that Czech classic); Frederick R. Friedel’s Axe (aka Lisa, Lisa, 1974) and Date With a Kidnapper (aka Kidnapped Coed, 1975), two strange regional films which start from exploitational premisses but, like Ganja & Hess and Lemora, go off in strange, unexpected directions.

All of these films were made by directors who made few if any other movies. Matt Cimber, who made The Witch Who Came From the Sea (1976), had a longer career, but nothing else in his filmography (softcore comedies and fantasies, blaxploitation, and the notorious Butterfly, starring Pia Zadora in her Golden Globe-winning adult debut) is anything like this strange, dreamlike story of a woman (Millie Perkins, of The Diary of Anne Frank [1959]) who exists in a world which drifts in and out of subjective fantasy and slides inexorably into violence driven by her repression of childhood sexual abuse by her father. This is a film which refuses simple exploitation pleasures in favour of a deeply disturbing dissection of pathological behaviour, all rendered in visually beautiful imagery and disorienting narrative strategies. Despite the seriousness and artistry with which Cimber approached his subject, Witch (like Friedel’s Axe) was placed on the banned list during the British “video nasties” uproar in the ’80s.

Huyck and Katz’s commercial claims notwithstanding, Messiah of Evil shares something with these other movies: a rejection of linear narrative clarity in favour of an emphasis on mood and disturbed psychological states, a blurring between subjective and objective perception which undermines any sense of a stable, rational universe. Messiah, like Lemora (made the same year) manages to evoke the ambiance of H.P. Lovecraft’s fiction far more convincingly than any of the direct adaptations made over the years; these films create a stifling air of paranoia steeped in a perverse kind of poetry.

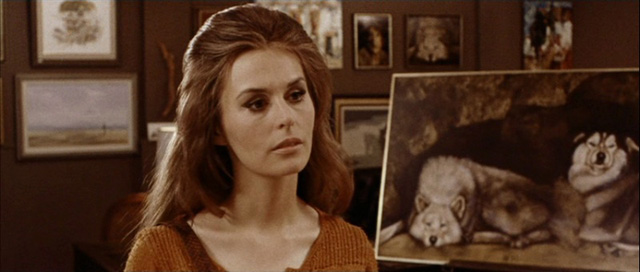

In Messiah, Marianna Hill stars as Arletty (a somewhat self-conscious reference to the great French actress) who drives to remote Point Dune in search of her estranged father, an artist who has apparently disappeared. She takes up residence in his modernist beach house, full of large, disturbing murals which give the impression of vaguely threatening figures crowding around her, while the locals seem hostile and unhelpful. A rich man, Thom (Michael Greer), and his two female travelling companions, Toni (Joy Bang) and Laura (Anitra Ford), force their way into the house and take up residence, leading to several levels of sexual tension as relationships transform and reality seems to dissolve around them.

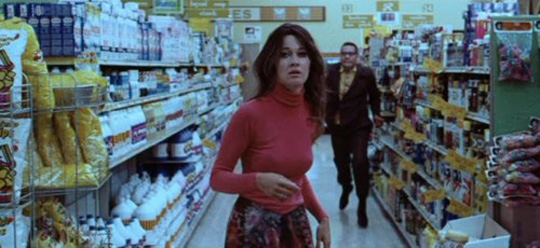

Arletty reads fragments of her missing father’s journal, full of indistinct intimations of danger and violence revolving around a mysterious figure who arrived in the town a hundred years earlier, was killed, but vowed to return. Now this stranger’s influence is apparently infecting the local population who are transforming into flesh-eating ghouls. There are two particularly powerful sequences: one evening Toni goes to the local movie theatre and the camera rests on her as we see the seats behind her gradually filling up with blank-eyed townsfolk. By the time she realizes she’s no longer alone, there’s no escape and the silent crowd close in and begin to eat her alive. In the other sequence, Laura goes to a strangely deserted supermarket at night and wanders the aisles until she turns a corner and sees another crowd of townsfolk gathered around the meat counter in the rear, munching on raw flesh.

There is no explanation given for what is happening, just an escalating sense of unease and despair. When Arletty’s father finally reappears, he too is contaminated and she is forced to destroy him …

Messiah of Evil is disturbing in ways that contemporary horror so frequently fails to be; the physical unpleasantness of things like the Saw and Hostel franchises makes you queasy while you’re watching, but they’re incapable of generating the sense of existential dread which is conjured by Messiah and other films from that brief period of creative freedom, when filmmakers weren’t afraid of ambiguity and open-endedness and producers were willing to take a modest financial chance as long as writers and directors tailored their work to what were considered commercially viable genres.

Footnote

1973, the year Messiah of Evil was made, also saw:

Blackenstein (William A. Levey)

Children Shouldn’t Play With Dead Things (Bob Clark)

Don’t Look In the Basement (S.F. Brownrigg)

Dr Death Seeker of Souls (Eddie Saeta)

Ganja & Hess (Bill Gunn)

Happy Mother’s Day … Love, George (Darren McGavin)

Hex (Leo Garen)

Lemora: A Child’s Tale of the Supernatural (Richard Blackburn)

Scream Blacula Scream (Bob Kelljan)

Seizure (Oliver Stone)

Barn of the Naked Dead (Alan Rudolph)

plus, of course, William Friedkin’s big budget, Warner’s-produced adaptation of The Exorcist.

Comments