Plumbing the depths of pulp

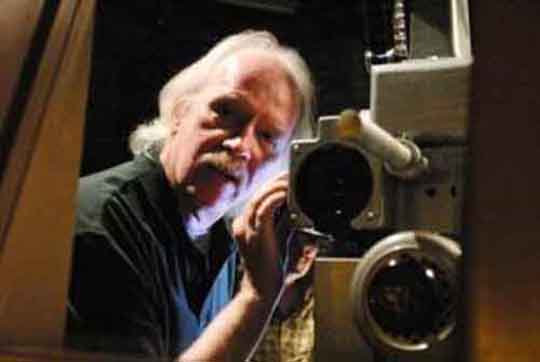

John Carpenter has had a long, uneven career, the chief foundation of which (after a couple of very good small features, Dark Star and Assault on Precinct 13) was the highly successful and influential Halloween. Personally, I’ve never understood that movie’s reputation and success. Apart from his facility with the widescreen frame and a strong and distinctive prologue, much of Halloween is exceedingly dull as it follows its over-aged cast of supposed highschool students through hackneyed situations which are occasionally interrupted by mechanical make-you-jump moments.

Halloween established Carpenter’s reputation as a “master of horror” … though much of his work isn’t actually horror; he tends more towards science fiction with some horrific elements. Though he has written many of his own scripts (as well as scripts for other directors), his best work after those first two features was written by others: The Thing (1982) by Bill Lancaster and Big Trouble In Little China (1986) by W.D. Richter. The scripts he’s written himself, either solo or in collaboration, are frequently characterized by good set up, but poor follow through. He gets a good idea but doesn’t seem to know where to go with it.

But as, essentially, a B-movie maker, Carpenter does manage to make some of those concepts entertaining enough that you get most of the way through the movie before a sense of disappointment sets in. I’ve had that experience with The Fog (1980), Escape From New York (1981) and L.A. (1996), Prince of Darkness (1987), In the Mouth of Madness (1984) … all movies which have their cheesy pleasures even though they ultimately fail to satisfy completely. And yet this is the level at which Carpenter seems to be most comfortable; his worst films have been those in which he aimed higher, trying for something more mainstream and “A” – the dull, sentimental Starman (1984) and the complete misfire, Memoirs of an Invisible Man (1992).

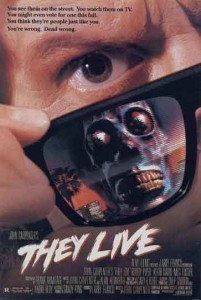

A friend recently gave me an intriguing little book by novelist Jonathan Lethem, part of a new series put out by Soft Skull Press called Deep Focus, in which writers (not critics) devote themselves to a particular film or film-related topic; in Lethem’s case, he tackles Carpenter’s 1988 sci-fi/horror/satire They Live. As I’ve always considered this a prime example of Carpenter’s weaknesses as a writer-director, I was intrigued by the idea of a book length analysis. Lethem’s method is virtually a moment-by-moment stream of consciousness response to the movie, prising out the many ideological and thematic contradictions and incoherencies in the narrative. This approach doesn’t result in a clearcut “interpretation” of the movie, but rather illuminates how even a piece of low budget pulp can embody numerous interesting ideas and effects, many of which may be completely outside of the filmmaker’s conscious intentions.

With virtually no budget to speak of, Carpenter quickly sets up a grimy dystopian near future in which a dispossessed working class lives in tent cities while surrounded by a vapid, consumption-obsessed society. A drifting worker (wrestler “Rowdy” Roddy Piper) arrives in Los Angeles and despite the economic situation quickly finds work on a building site, where he meets another working man, Frank (Keith David), who takes him to the squatter community called Justiceville, where the homeless seem to spend a lot of time vegging in front of television screens showing shallow news shows or old movies (John Sherwood’s great ’50s sci-fi, The Monolith Monsters).

Nada (as he’s named in the credits, though we never hear him called that) begins to notice odd things: the TV shows get occasionally interrupted by a ranting character warning of some vague conspiracy; he sees something surreptitious going on at the church across the street from Justiceville; a blind street preacher warns of some all-consuming threat …

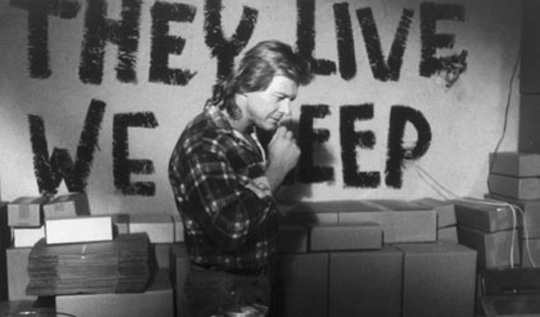

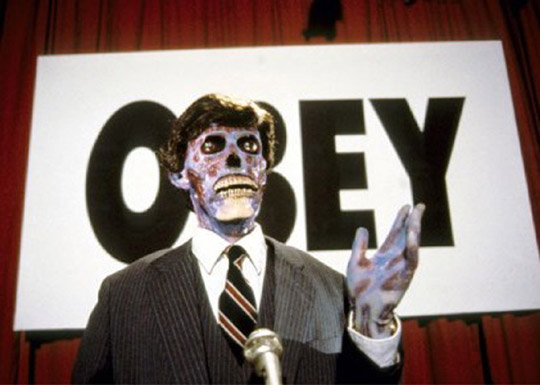

Eventually, Nada discovers the truth of this world when he puts on a pair of sunglasses manufactured by members of an underground resistance group working out of the church – the yuppies among us are hideous aliens concealed by a global jamming signal which lulls the human population and makes them see a consumerist fantasy landscape which saps their will, making them placid fodder for the aliens. A bit like a low-tech Matrix, in fact. The highlight of the movie comes in the lengthy sequence following Nada’s new awareness as he sees this bleak reality which is a colourless complex of subliminal messages telling all humans to stay asleep, to consume, to obey authority … beneath the surface illusion, he discovers that money is really just blank pieces of paper with “This is your god” printed on it.

Carpenter made They Live at the height of the Reagan era, as Reagan’s economic policies were kicking into gear and social disparities were escalating. The satire is quite crude and blatant, but watching the film again this past week, the point actually seems even more pertinent now than when it was made. It’s almost comforting to believe that the economic elite are not merely different from the rest of us, but are actually malevolent aliens who have come to enslave us.

Unfortunately, having set up this nifty satirical structure, Carpenter doesn’t explore it any further, but rather shifts gear and goes into full pulp action mode. (In the brief EPK included on the region 2 DVD, Carpenter says that these themes are there, but he’s really just out to make entertainment.) The quiet, observant working man immediately goes medieval on alien ass, killing a couple of alien cops, stealing their weapons and blasting his way through a bank before kidnapping a (human) woman and forcing her to take him back to her home on a steep hillside. From this point on, Nada is on the run and fighting. But he feels the need of an ally and approaches Frank. He wants to get Frank to put on the sunglasses and see the truth; but Frank doesn’t want to get involved with a killer on the run, let alone see what really lies beneath the daily grind of his life.

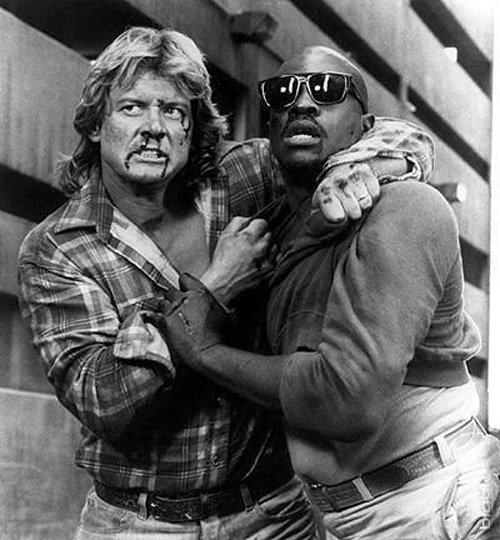

And this is where the movie lost me the first time I saw it. Carpenter takes a peculiar risk by bringing the entire narrative to a stop while Nada and Frank beat the crap out of each other in a back alley, Nada demanding that Frank put on the glasses, Frank refusing … for six whole minutes! What begins as a somewhat gratuitous bit of man on man action stretches out to the breaking point, becoming a strange bit of absurdist theatre, then it keeps going on and you start to get the feeling that this may even be some kind of joke on the audience – “you came to see an action movie starring a wrestler, well here’s what you get”.

Lethem says: “How to legislate between these two great constituencies: those who love They Live for the fight scene, and those who love it despite the fight scene. Indefensible by its deep design, the ‘longest fight scene in movie history’ (according to Carpenter …) expands in cultural memory as an artifact unto itself, an object if not of study then of wonder, a legend, a contested site, a nihilistic gesture, a secret code or ritual, possibly akin to Fight Club before Fight Club … Really, it’s more like two characters in a movie quitting the script in order to beat the shit out of each other, more or less persistently, but with quasi-realist breaks to catch their breath, for six minutes.”

When I saw They Live back in 1988, this scene pushed me right out of the movie and all the macho, alien-killing combat that followed seemed like yawn-inducing cliche. I have to admit that what Lethem discerns in the sequence does make it seem more interesting, and even more pertinent to the narrative, than it first appeared – he highlights a number of small details which actually illuminate aspects of the characters and what’s at stake for each of them at this point. So I’m willing to concede that, as absurd as the fight is, it may not be entirely gratuitous.

Unfortunately, the action which follows – all that alien-killing combat – remains for me dull and formulaic, though now thanks to Lethem I can see a handful of odd little details that boredom had previously blinded me to (the pregnant secretary with the coffee pot in the middle of a firefight).

Lethem claims to have watched They Live at least a dozen times, and individual scenes many more … you might ask whether that’s really a wise investment of time, but it has in any case resulted in a fascinating and entertaining book, one which spurred me to go back and watch the movie again. Lethem hasn’t really changed my opinion of They Live, but he has reminded me that even a minor, conceptually confused, budget-challenged movie like this can harbour a multitude of interesting facets, whether intentional or not, which can be seen and contemplated if you’re willing to invest the time and energy.

Comments

I think Lethem reminded you why you, yourself, invest so much time in low-budget, less than stellar movies, and why it can be worth the effort. Sounds like a great book. Unlike you, the sun-glasses fight scene did not ruin the movie for me. I always felt like I had stepped out of one theater where I was watching a cool SF/Horror movie into another playing a weird comedy, then wandered back six minutes later to see the end of the movie I’d paid to see. I always found myself smiling and laughing through that scene. Must watch it again.

Agreed … that’s probably why I enjoyed the book. I like watching this stuff, so it’s nice to have someone smart validate the activity!