The real pleasure of fake commentaries

Back in the dark days before DVD, when elitists spent large sums on laserdisks because the quality was so superior to the ubiquitous VHS tapes of home video, the commentary track was born. This was a terrific innovation, enhancing the value of a movie by providing context and opinions from the actual filmmakers or from critics and historians. No longer simply mere home entertainment, if you were willing to pay the fairly hefty price for a player (and the expensive disks themselves), you could home-school yourself in the art and history of film.

Back in the mid-to-late ’90s I took full advantage of this technological wonder. Whenever I watched a laserdisk which offered a commentary, I would immediately sit through it a second time listening to the alternate track. And while there was an occasional dud – an unprepared filmmaker with little to say, long stretches of dead air – for the most part I really did find my appreciation for the movie in question enhanced to some degree.

Then came DVD, a more populist format. The players quickly dropped in price, the disks were reasonably cheap (far cheaper than laserdisks, not much more than an average VHS – and far more compact and easily stored than either), and they quickly supplanted tape and became the sole medium for home video. And of course, the format offered a far wider range of titles than the more specialized laserdisk ever could have.

During the transition from tape to DVD, manufacturers needed to do whatever they could to attract consumers away from VHS and one of the things they did was to adopt the methods of special edition laserdisks – adding documentaries, deleted scenes, various other production ephemera … and naturally, the commentary track.

For a while, I continued my habit of listening to every commentary track on offer, but these days I no longer make the effort much of the time. With so many movies available, I had to become more selective. And then, because commentaries had become a more or less default extra, it was apparent that fewer filmmakers were making much of an effort, some barely showing up in the recording studio – while others indulged in exhausting overkill (do David Fincher and Edgar Wright really need four separate commentaries to say what they need to about their movies?).

One method I developed a few years ago to listen to tracks I was interested in while at the same time not cutting into my limited viewing time, was to use DVD Audio Ripper to convert commentaries to MP3s, which I’d then listen to on my iPod while doing other things. I did that with the multiple commentaries on last year’s Thriller box set, which initially enhanced my two-week binge of watching all 69 episodes back-to-back, but with the same commentators reappearing on multiple episodes, there were diminishing returns, a lot of repetition … even the most knowledgeable authority on the show could eventually run out of interesting things to say and some of the later tracks devolved into aimless chatter.

I had a somewhat revelatory moment, it must be almost ten years ago now, when I listened to the track on the General’s Daughter disk, during which director Simon West related an anecdote about a famous actor (I can’t recall who now) which ended with the star saying something like “But, Simon, you ARE cinema.” I laughed so hard that I perhaps missed several minutes of genuine insight into that mediocre movie. That was the moment when I first clearly doubted the necessity of a commentary on every movie being released.

Which is not to say that the form had become valueless – the producers at Criterion still offer excellent critical/historical commentaries on many of their releases, as did Warner and Fox on their (now apparently exhausted) noir editions, David Kalat knows his stuff when it comes to Lang and Feuillade, and Tim Lucas is a terrific guide to the work of Mario Bava (I’m still kicking myself for failing to nab a copy of Dark Sky’s edition of Kill Baby Kill which featured his commentary; it was quickly withdrawn right around the release date because of a rights issue, but you can still find an occasional used copy on Amazon for around $100).

So, while I do still occasionally listen, I’ve realized that what I enjoy most now are what you might call bogus commentary tracks. These generally involve cast members performing a commentary in character – obviously this is something which works only with comedies – and at its best the technique expands and enriches the film in question in ways which a straightforward production commentary never could. Interestingly, this is also something which originated on laserdisk, the first that I’m aware of being Criterion’s edition of This Is Spinal Tap, with the “band members” and “director Marty DiBergi” flawlessly, and hilariously, responding to the film as an actual document of their lives – it was like suddenly having a whole new version of a favourite film, just as rich and funny as the original.

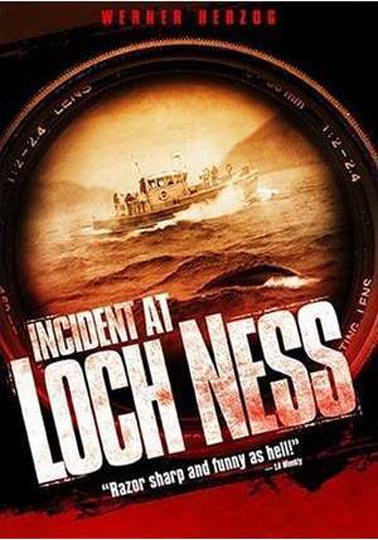

Since then there have been others, a few of my favourites being Bruce Campbell as Elvis talking about the making of Bubba Ho-Tep; the creators/cast of the brilliantly funny Channel 4 series Garth Marenghi’s Darkplace revisiting their catastrophically bad horror series set in a hospital not unlike Lars Von Trier’s Kingdom; and Zak Penn’s equally brilliant Incident at Loch Ness.

One of the keys to this kind of meta-filmic comedy is that the original film itself, the artifact on which the “commentary” is based, has to be note perfect, and work on its own terms. Spinal Tap of course is one of the best documentaries about rock music and the culture of rock ever made, even though the band is “fictitious” (really? … the performers write and play their own material, they give concerts; this can get philosophically confusing as we start to debate what constitutes levels of reality). Darkplace is that very rare creature, a completely successful attempt to create something deliberately bad, doing it with an obvious wealth of knowledge about bad horror movies and the comic skills to make it appear that the people involved are completely unaware of just how bad it all is. This is enlarged on in the very funny commentaries on all six episodes in which the three principals bicker, argue, joke, and reveal the oblivious depths of their own lack of self-awareness as they look back on the making of the show in the ’80s (although of course the whole thing was actually created in 2004).

Incident at Loch Ness is possibly the greatest example of this new kind of art form, beginning with the film itself – it starts with cinematographer John Bailey setting out to document a new Werner Herzog production and gradually turns into a comic revisioning of Les Blank’s classic Herzog documentary Burden of Dreams, about the making of Fitzcarraldo. In Incident, Herzog (brilliantly played by Werner Herzog) travels to Scotland to make a documentary about the myth of the famous monster in Loch Ness, a subject perfectly in keeping with his documentaries about obsessions and extreme experience. But he’s saddled with a crass, opportunistic producer named Zak Penn whose schemes for turning the film into a money-maker constantly run headlong into Herzog’s more serious intentions. Incident is a terrifically detailed account of a production gone wrong – up there with Blank’s film and Keith Fulton and Louis Pepe’s Lost in La Mancha, about Terry Gilliam’s disastrous attempt to film Don Quixote.

Incident at Loch Ness wasn’t very well received when it was released, to a large degree because it confused too many people about whether it was fact or fiction (Roger Ebert’s review is an amusing example of a smart guy obviously hedging because he’s worried that someone might be trying to make a fool of him). Strangely, though, the clues are all there: Zak Penn, the filmmaker, makes a colossal buffoon of himself as Zak Penn the producer; towards the end when disaster strikes in the form of an apparent encounter with the real monster which results in crew deaths, it’s impossible not to perceive the fiction, as well-executed as it is – after all, if Herzog had actually run into the real Loch Ness monster wouldn’t it have been on the news? But while there are these giveaways that Incident is indeed a fiction, and a very funny one, Penn never falters in the tone of authenticity he establishes at the beginning with an obviously real dinner party at Herzog’s L.A. house attended by Bailey and others who all appear as themselves.

But what raises Incident to the very crest of this small wave of meta-fictional DVD artifacts is the elaborate and sustained structure of the DVD itself. I don’t think I’ve seen any other that’s been made with such a sophisticated awareness of the possibilities of the medium. First, there’s the film itself, one of the finest faux documentaries yet made; then there’s a collection of making-of materials, including a commentary, which continue the conceit that the film is genuine. Penn starts off the commentary with Herzog in the recording booth; but soon stresses and unresolved issues lead to a falling out and Herzog angrily leaves; Penn begins to drag other people in, but in every case the rancour causes a split and he’s left desperately alone – he eventually drags someone off the street who hasn’t even seen the film, and finally just gives up before the halfway point.

But beyond this, using hidden Easter Egg buttons in the menus, Penn has added yet another layer, this one the apparently genuine account of the making of the real mock film, with behind-the-scenes features and another full-length commentary which talks about the actual making of the film and the idea of playing off Herzog’s well-known persona as a serious, obsessively driven filmmaker.

I’ve watched this film many times, and sampled the various surrounding materials on a number of occasions, and it just seems to get richer and funnier the more you look at it. There’s a whole thesis’ worth of material on how we watch and receive movies, how we are affected by external factors like our prior knowledge of the people involved, or the subject at hand (what better MacGuffin for a project like this than the famous, elusive Loch Ness monster?), and the powerful issue of trust – as evident in Ebert’s and others’ reviews at the time, that uneasy suspicion that some filmmaker might be trying to put something over on us but we can’t quite be sure.

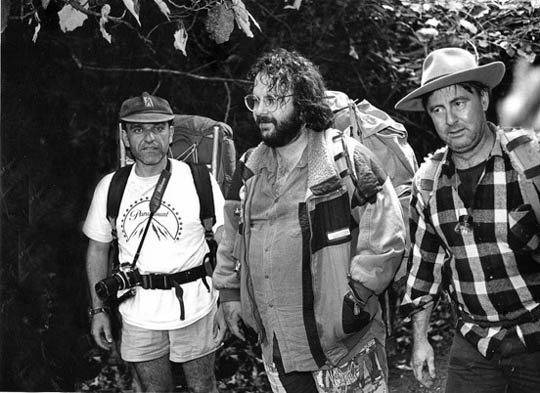

As a footnote, something similar happened with one of Peter Jackson’s finest works (before he succumbed to the terrible weight of epic bloat and destroyed himself as an interesting filmmaker). Forgotten Silver is a television documentary made with Costa Botes in New Zealand in 1995. Starting with the discovery of a remarkable cache of old film cans which someone had discovered in a shed, the film traces the no-longer-remembered life and career of the pioneering Colin McKenzie, who apparently pretty much invented every advance in filmmaking from the silent era on, working away unheralded in New Zealand and eventually forgotten completely. It’s a wonderful exploration of the history of film production and technique, the development of technologies and styles … and all built around a non-existent historical figure and clips from movies which never were. It actually has a lot to say, with great warmth and affection, about that history, but it is nonetheless a fiction.

When it was first shown on New Zealand television it stirred some pride and wonder in viewers who had never heard of McKenzie … with a consequent burst of anger and resentment against the film and Jackson when those same viewers realized that they had been “had”. It’s a tricky game that a filmmaker plays with the audience, but in some ways it’s only a variation on the game that every filmmaker plays with every audience: while you’re there in the dark, committed to what’s flickering up there on the screen, you the viewer want, and the filmmaker behind the scenes wants you, just for a little while, to believe that it’s all true.

Comments