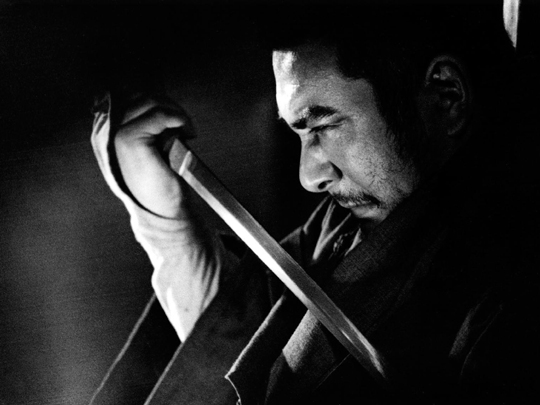

The two sides of Shintaro Katsu

I first encountered the actor Shintaro Katsu back in 2002 when I picked up the first two movies in his long, defining series about the blind masseur/master swordsman Zatoichi. Although Katsu had a long and prolific career (IMDb lists 119 titles in 35 years of acting), having made 25 features about Zatoichi between 1962 and 1972, with an additional 112 television episodes in the mid-’70s and a final, elegiac feature (written and directed by Katsu) in 1989, he is indelibly identified with the character.

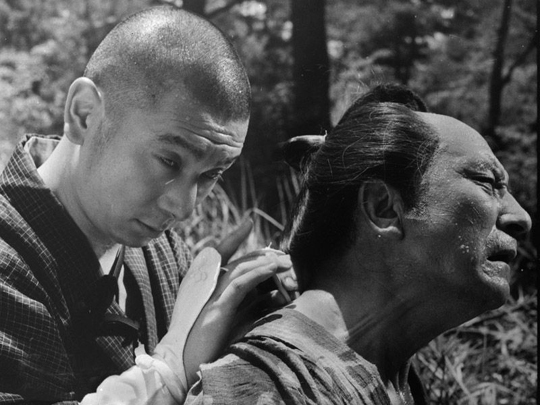

At first glance, the concept seems ridiculous: a humble blind masseur wanders the dusty roads of feudal Japan, moving from village to village, trying to make a meagre living. But when he gets drawn into situations almost invariably involving local factions of gangsters and gamblers who prey on innocent peasants, he reveals himself to be the fastest, deadliest swordsman in the country, his blade flashing from the plain stick he uses to guide himself and cutting a swath through the ranks of bad guys who can’t believe he isn’t what he appears to be.

And yet, Katsu’s skill in playing both sides of the character precludes any disbelief the audience might hold. His nuanced mannerisms convince us that he is blind, while his almost balletic physical performance during the fight scenes, in which he is guided purely by a preternatural sensitivity to sound, is so impressive that we’re completely willing to believe in it.

As with any long-running series involving multiple writers and directors, particularly one which switched studios late in the series, the quality of the Zatoichi films fluctuates, but having seen 25 of them (the rights to number 14, Zatoichi’s Pilgrimage, were bought by Miramax years ago for a possible Tarantino remake; it now drifts in rights limbo, the only one of the series unavailable in region 1 – the Weinsteins strike again!), I can say that every one of them is entertaining, many of them are charming, occasionally poetic in their widescreen images, and together they amount to a substantial contribution to chambara, the Japanese genre of sword-fighting films (the Japanese equivalent of the western).

I will say that the later Toho-produced features, while having bigger budgets and a larger sense of scale, lack some of the original charm of the Daiei films, tending to focus more on action than character. But throughout the series there is a sense almost of ritual (as in the classic western), a set of repetitions and reiterations which, rather than becoming stale, actually provide the series with much of its pleasure. Zatoichi is an inveterate gambler and in almost every film the first thing he does when he arrives in town is seek out a dice game; the locals are amused by the idea of a blind man gambling, and invariably try to cheat him, leading to the first demonstration of his swordsmanship (often the almost invisible slicing in half of some object like a candle or a dice cup). These scenes are anticipated by the viewer and serve to initiate the action which then leads inexorably towards the final showdown.

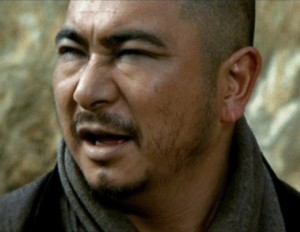

It was the absence of the gambling scene in Takeshi Kitano’s reworking of Zatoichi (2003) that triggered a sense of disappointment that only grew stronger as the film played out. While the entire series is shot through with elements of humour, they almost invariably come from Ichi manipulating the contempt others show towards him because of his lowly station; he plays on their expectations of him being a nobody, exaggerating his blind clumsiness, his humility. Kitano, however, couldn’t seem to resist mocking the character, adding a layer of knowing irony which refused to take Ichi seriously, which of course goes entirely against the grain of the whole series.

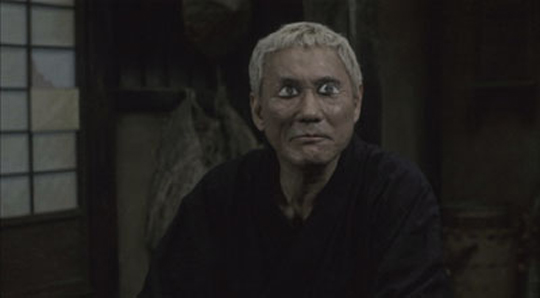

What I didn’t know until recently was that the character had its origins in a much darker story, in fact almost a mirror image. The Blind Menace (1960), directed by Kazuo Mori, who also directed three of the Zatoichi features, was something of a breakthrough for Katsu, who had spent the previous five years as a Daiei contract player in a variety of genres. In The Blind Menace, he plays Suginoichi, first seen as a blind child practicing various scams to make money and provide sake for his impoverished mother. This conscienceless boy grows up with an ambition to become the foremost masseur in the kingdom, lying and stealing to finance his plans, allying himself with a criminal gang in blackmail and robbery schemes, and eventually murdering his mentor in order to take his place. Interestingly, Katsu plays Suginoichi with most of the mannerisms which would come to define Ichi just two years later, but all applied to a ruthless sociopath rather than the protector of the innocent he would soon become. (That dark side is also apparent in a more unpleasant way in Katsu’s Hanzo the Razor trilogy [1972-74], in which he plays a particularly unsavoury, sadistic magistrate who gleefully tortures suspects and witnesses in a very particular way using a particular anatomical tool.)

The Blind Menace is less well-crafted than most of the Zatoichi films, its plot ragged and episodic, never quite coming together into a satisfying dramatic whole. But Katsu’s relish in the role makes it obvious why he took so strongly to the later role; Ichi is a kind of superhero whose powers are rooted in his apparent handicap, providing the actor with a great showcase for his emotional and physical range.

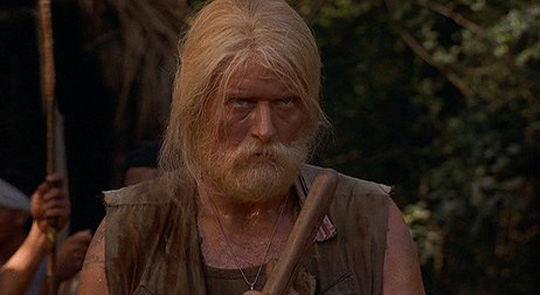

Footnote: In 1989 director Phillip Noyce made Blind Fury, one of his weakest films, based on the 17th film in the series, Zatoichi Challenged (Kenji Misumi, 1967). This updated the story to post-Vietnam America with Rutger Hauer as a blind vet named Nick who was trained in the art of sword-fighting by villagers who rescued him from a helicopter crash; twenty years later, he wanders the highways of the southern States looking for his former buddy who was partially responsible for his blinding. He gets mixed up in a plot to kidnap the friend’s son in order to force the man to produce “designer drugs” for a Reno kingpin. Nick rescues the boy and crosses the country to reunite him with his father, while remarkably inept bad guys pursue them. The movie finds it impossible to take the character seriously (and who can blame it? Hauer wielding his sword cane against a crowd of Uzi-toting thugs and defeating them again and again lacks any of Zatoichi’s poetic plausibility), and the whole thing is perfunctory and unengaging.

Comments

I’ve been a follower of Shintaro’s blind swordsman. Unluckily he’s now dead.

In fact, the Katsu’s role of Ichi is more consistent and close to Japan spirit than more of Kurosawa’s samurai movies in the same period. It is hard for me to say it, but somehow its surpasses even Toshiro Mifune’s samurai characters. On the other side, the latest remake’s are all shamefuly failures, because the entire cinematography has changing the paradigma – superficial, violent/erotic, unethic und imorral characters rules after aprox. 1990. Big characters, great scenarios and directors are merely accidents, compared with years 60-70’s period of gold era in cinema.Sincerelly yours.

It is hard to say whether Ichi is “more consistent and close to the Japan spirit” because it depends on what we define as that spirit; the spirit of the more progressive side or the traditional side? Both the Zatoichi films and the Kurosawa samurai movies were essentially left-wing critiques of society, though the Zatoichi movies had more a sense of fun and Kurosawa more a sense of gravitas.

I seen them alL blind fury first back in the day on TV when I was a kid my father grew up watching Zatoichi back in Hawaii. I got lucky & was able to watch most the original Zatoichi movies on the IFC channel commercial free when they had Samurai Saturdays. I was around 15 then. Watched the remakes of course I liked Kitanos remake but not as much as Ichi or the originals of course. Love them movies Mr. Katsu was a very entertaining & funny man . May he rest in peace.

I recently dis overed Shintaro Katsu’s portrayal of Zatoichi, and the imensity of his quiet charm and humble, world weary yet vibrant and invulnerable Zatoichi has made me a very happy and thoroughly entertained individual for the forseeable future, thanks to the amazing body of work! I discovered him quite by accident looking through some samurai reels on YouTube, and I have been enthralled by this man’s amazing talent on my computer screen through the early hours of the morning for the last two days, and I look forward to many more hours of enjoyment.There is a great charm in the humour and humility of the portrayal by Shintaro that I find gives me hope for humanity, despite the fact that the series is decades old and Shintaro Katsu is no longer with us.Domo Arigato Shintaro, we need heroes like you in this dark age now, and alas, your like cannot be found among the living.

I encountered one of the Zatoichi films in 1970 in one of the neighborhood theaters in New York City. It was “Zatoichi On The Road”, and actually it was dubbed in English and when DVDs became very popular and I brought several DVDs of the movie series home and I discovered the TV show on YouTube recently and I love the series. I wish I could have met Mr. Katsu and let him know how wonder the series is and my respect for his acting.

Zatoichi’s depiction of Japan at that time was believable and gritty. I enjoyed that. His gang affiliations and toughness made his character that much more sympathetic whenever he disavowed that lifestyle. He was doing what he had to do.