DVD Review: The Making of the President: The 1960s

In the 1960s several factors came together to change the way American politics was both played and perceived, and the journalist Theodore H. White played an important role in the second part of that equation. With his Pulitzer Prize-winning book The Making of the President 1960, he brought the processes of presidential electoral politics out into the open, and he did this fortuitously at the same moment that John F. Kennedy came to power. It was at this moment that the conservative stability of the Eisenhower ’50s began to give way to powerful social and cultural upheavals which, throughout the next decade, would transform the nation in ways which are still echoing today.

But White’s book was just a part of the evolution in the way politics was perceived. At the same time, television was becoming more pervasive and powerful as the chief purveyor of information and opinion. The growing omnipresence of television meant that there was now a wealth of material – picture and sound – covering the processes White wrote about in his book, so it was almost inevitable that someone like the prolific producer of documentaries David L. Wolper would seize the moment and bring White and that archival material together to produce what became the first of a series of feature-length television documentaries called The Making of the President.

Athena have just released a fascinating three-disk set containing the programs covering the elections of 1960, 1964 and 1968, providing us with a remarkable portrait of both the time and the ways in which that time was presented to itself in the media.

While the focus of each documentary is one particular election, watching the three together gives us something larger, a glimpse of the tectonic social shifts the country underwent as the war in Vietnam escalated and the counter-culture developed in response. In addition, they illustrate the remarkable achievement of the space program which was given impetus by Kennedy’s famous speech committing the nation to putting a man on the moon by decade’s end, a goal ironically achieved after the Democratic Party collapsed from the strain of the war and Richard Nixon had taken the White House.

Against this background of social and technological change, each of the three documentaries details the struggles within the two parties in nominating their candidates for president, and between those nominees once the election gets underway. In retrospect, The Making of the President 1960 seems refreshing in light of the abrasive media-driven politics we see today. Kennedy and Nixon exchange insults which seem more tinged with humor than malice, and within both parties there were conflicts between right and left factions.

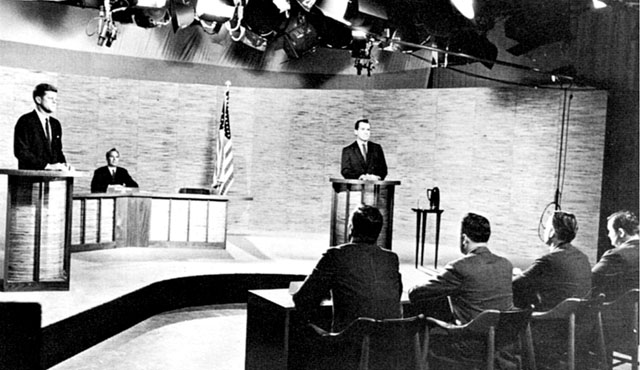

Kennedy had to fight for the nomination against the internationalist Adlai Stevenson and the experienced political insider Lyndon Johnson; Nixon was up against the “radical” Nelson Rockefeller and the conservative Barry Goldwater. But once the jockeying for position and the backroom dealing had resulted in Nixon and Kennedy getting their respective party’s nomination, the real game-changer arrived with the first televised debate between the candidates. In many ways, this was the moment when image began to become more important than issues: Kennedy became a star. And yet, the election itself was very close.

By the time of the 1964 campaign, following the Kennedy assassination, Johnson entered the election with some solid legislative achievements, particularly his work on civil rights. On the Republican side, Goldwater stood against any kind of civil rights legislation, seeing it as a violation of States’ rights. Interestingly, much of what Goldwater said during the campaign sounds like the rhetoric of the Tea Party today, and he built a powerful grassroots campaign that helped him defeat Rockefeller for the nomination. The divide between liberals and conservatives was deepening as the country became increasingly bogged down in the war. But despite the escalation under Johnson, there was widespread distrust of Goldwater and the Democrats won in a landslide.

By 1968, the sense of optimism present in 1960 had devolved into confusion and uncertainty; the war dragged on, there was powerful resistance among students and blacks. Again, television played a part as it broadcast a constant stream of disturbing images from Vietnam which inevitably counteracted any attempts by the government and the military to put things in a positive light.

As the campaign got underway, Johnson declared that he wouldn’t seek reelection and Eugene McCarthy stepped in to appeal to the angry youth vote; standing against him was Hubert Humphrey, who appeared to be from the old guard, a supporter of the war. As the Democrats struggled to find a stable position, Robert Kennedy declared his candidacy, but McCarthy was still ahead going into the California primary. The votes were still being counter when Kennedy was assassinated.

Nixon found himself opposed by both Rockefeller and Ronald Reagan for the Republican nomination. Rockefeller had popular support but was distrusted by party insiders; Reagan pushed for law and order to crush the dissent in the streets. Against them, Nixon seemed to represent calm and stability and he won the nomination.

The Democrats were foundering by the time of their convention in Chicago. Protesters in the street called for an end to the war, but the party rejected their demands. While riots raged in the city’s streets, Hubert Humphrey bought TV time to announce his break with Johnson’s war policies, and George Wallace joined the race, appealing to those who feared youth rebellion and racial unrest.

In the end Humphrey gained the nomination and the election was extremely close, with Nixon winning the electoral college majority he needed to gain the White House. Yet the results left all the major conflicts unresolved … and many of the social and political issues of that time remain unresolved now, more than forty years later.

So much for the history presented in The Making of the President: The 1960s. What about the documentaries as film? Although these programs won awards in their day, looked at now they can be quite frustrating. In form, they evolved out of television news; Theodore White’s scripts insist on telling the audience not only what we are seeing, but what it all means. Particularly in the first two programs, the narration is virtually non-stop and we seldom get a chance to hear what the historical figures have to say for themselves. This is far from the kind of thing we see in a documentary like Chris Hegedus and D.A. Pennebaker’s The War Room (1993) about Bill Clinton’s first presidential campaign, and at times you wish the narrator would shut up and let us hear what the candidates actually had to say.

Technically, all three programs are quite rough, the black and white newsreel footage very grainy and the sound often less than clear, though the quality improves a bit in the 1964 documentary. However, the shift to colour in the third part is an eyesore, the images often murky and soft.

But quality issues aside, Athena’s three-disk set is a fascinating time capsule from the decade in which the modern combination of politics and media was forged, and the lines between left and right began to harden.

The set contains two major extras: a half-hour tribute to JFK, A Thousand Days, shown at the 1964 Democratic convention. This, along with an essay that White wrote for Life magazine at Jacqueline Kennedy’s request, formed the basis of the myth of the Kennedy Camelot. The second extra is Seven Days in the Life of the President, a look at LBJ in office.

There are also brief text notes about what happened to all the candidates in their post-election careers.

Comments