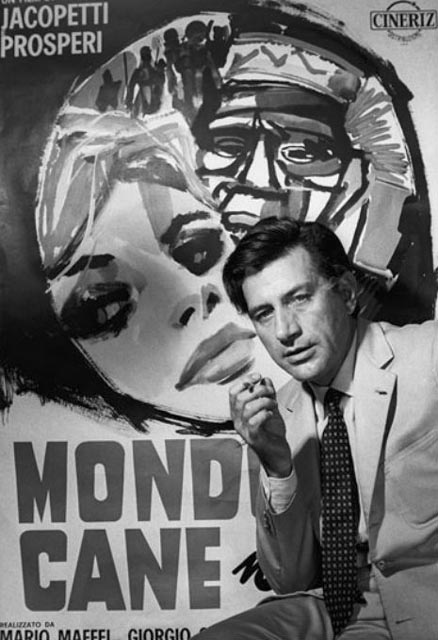

Gualtiero Jacopetti (1919-2011)

Italian journalist and filmmaker Gualtiero Jacopetti died August 17, at age 91. Together with co-director Franco Prosperi, Jacopetti invented what became known as the “mondo” movie – after the title of their first collaboration, Mondo Cane (Dog’s World, 1962). The essence of the genre was shock – documentaries that displayed strange, disturbing aspects of human behaviour around the world. But what later imitators missed in Jacopetti and Prosperi’s original was the dark, satirical humour and the underlying political edge. By juxtaposing supposedly “uncivilized” rites and rituals of Third World countries with the extremes of privileged Western consumer behaviour the directors threw the audience’s sense of smug superiority back in its face. The shock was always there for a purpose, and Jacopetti’s contempt for the decadent culture which surrounded him suffused his work.

Most critics at the time were appalled by the tastelessness of Mondo Cane and its sequels – Women of the World and Mondo Cane 2 (both 1963) – but there were others who could see past the superficial affront to the more serious purpose. As the Guardian‘s obituary points out: “The ambiguity of any political message shocked critics but delighted the novelist J.G. Ballard, who incorporated the aesthetics of Jacopetti’s aggressive film style, and a fake ‘Jacopetti exhibition’, into the narrative of his fragmentary novel The Atrocity Exhibition (1970).”

In the late ’60s, Jacopetti and Prosperi created their two masterpieces, epics of the form which brought down more censure and finger-wagging: Africa Addio (1966) and Addio Zio Tom (1971). The first is a broad survey of post-colonial Africa, a film so crammed with shocking imagery that it numbs the viewer as it delineates the chaotic consequences resulting from the mess left by the European powers when they departed, having shattered all the pre-colonial political and social structures of the continent. Perhaps it’s not surprising that there was an attempt to shoot the messenger when the film was released, with the directors being accused of having paid rebels and guerillas to commit murder for the cameras. The charge was later discredited by the Italian courts, but damage was done to the filmmakers’ reputations … diverting attention away from the film’s political message.

The second film deals with the history of slavery and the slave trade, reconstructing that institution in great detail as if the filmmakers had been able to go back in time and record the horrors inflicted by Europeans and Americans on the kidnapped populations of African tribes. Addio Zio Tom was inevitably greeted with disgust and disapprobation, but you have to wonder: how could the subject be treated “tastefully”? By necessity it has to be shocking and repulsive (Richard Fleischer’s politically and historically astute Mandingo [1975] met the same kind of response, for the same kind of reasons). The film combines its historical material with depictions of continuing racism and oppression in contemporary America. Even though the distributors forced Jacopetti and Prosperi to tone it down for North American exhibition, Pauline Kael still called it “the most specific and rabid incitement of the race war.”

Both of these major films were released in North America in edited versions, which managed to water down the political content. The differences between the original and U.S. versions are perhaps reflected in the differences between the Jacopetti obituaries published by the Guardian in England and the New York Times in America. The latter emphasizes the shock element in Jacopetti’s work, the eagerness to cause affront to good taste, keeping it on the level of the “mondo” genre, quoting Pauline Kael’s comment that anyone who liked Mondo Cane was “too restless and apathetic to pay attention to motivations and complications, cause and effect.” The two most important films are passed over quickly without any indication of their scale and complexity. The Guardian, on the other hand, takes a more serious approach, recognizing the political dimension of the films as well as the sophistication of their technique.

Although Blue Underground’s superb 8-disk set of Jacopetti and Prosperi’s films is out of print, individual titles are still available and worth seeking out.

Comments