DVD diary: September – part one

There’s still no recognizable pattern to my DVD watching, but maybe I shouldn’t worry about it. If my viewing became more systematic, it would probably start to feel like work.

I finally finished getting through the British TV series Department S, which I mentioned a while back. It never really improved, though perhaps the production values were a bit less shoddy towards the end, but for some reason in the later episodes the characters seemed to be in a constant state of anger with each other. Maybe they were all getting tired of the strained plots and the poorly matched stock footage and shabby studio sets. The brightest spot was the sudden, unexpected appearance of a very intense 32-year-old Anthony Hopkins in one of the later episodes, A Small War of Nerves (January 1970), as a chemical warfare researcher so appalled by his own work that he decides to release a deadly gas in the middle of London to show the world how bad it is.

Strange Report (1969-70)

I also just finished watching another series from the same period, Strange Report (1969-70), which has a very similar set-up – three investigators, two men, one woman, taking on crimes which baffle the official police. But in every respect, this one is superior. With the classically trained Anthony Quayle as forensics expert Adam Strange, the tone is immediately set for a more serious collection of stories which take on such issues as illegal immigration and racism, anti-war protest and campus unrest, Cold War conflict. Strange’s sidekicks are a young American lab technician and the attractive model who lives next door (seemingly a step down from Department S‘s computer expert, but Anneke Wills’ Evelyn McLean tends to get more deeply involved in the cases at hand). The writing, direction (mostly by Charles Crichton, Peter Duffell, Peter Medak and Daniel Petrie) and production values are all excellent, yet the show lasted only half as long as Department S and there was no spin-off like the inexplicable two seasons of Jason King (1971-72) in which Peter Wyngarde’s insufferably smug Department S character carried on solo.

Sherlock Holmes (1939-46)

And while I’m talking about mystery series, I finally got around to watching the complete Basil Rathbone-Nigel Bruce Sherlock Holmes oeuvre. Although the series has a good reputation, I’d previously been put off by seeing a couple of the early Universal episodes in which the stories were updated to World War Two, with Holmes tackling Nazi spies. I’d found this so annoying that I hadn’t bothered with the rest of the films before, but MPI’s recent Blu-ray set seemed like a good excuse to check them out.

The first two films were fairly prestigious Fox productions with appropriate period settings. Not surprisingly, the studio started with Hound of the Baskervilles (1939), always the most cinematic of the stories with its fog-shrouded moors and the giant phantom hound. Director Sidney Lanfield (who also directed the 1950 Esther Williams vehicle Skirts Ahoy, mentioned recently in my post on Antonioni’s I Vinti) did a fairly good job of evoking the gothic atmosphere, although the hound itself was rather toned down (an error later corrected by Roy William Neill with the eerily glowing killer-on-the-moors in The Scarlet Claw [1944]). The same year’s follow-up, The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes, directed by Alfred Werker (a busy studio employee perhaps best known for his sharp documentary-noir He Walked By Night [1948]), was based on William Gillette’s play rather than one of Conan Doyle’s stories. The cat-and-mouse between Holmes and Moriarty (an excellent George Zucco) is entertaining, but the criminal genius’s plan to steal the crown jewels quickly falls apart and the professor is too easily defeated. (In fact Moriarty plunges to his death three times in the course of the series.)

With Fox having decided not to pursue the series despite the success of the first two films, the rights went to Universal and they began their more cheaply produced, updated series three years later with Sherlock Holmes and the Voice of Terror (John Rawlins, 1942), Sherlock Holmes and the Secret Weapon and Sherlock Holmes in Washington (both Roy William Neill, 1943). After the Washington foray, it was realized that Holmes fans were not all that interested in seeing the great detective in the thick of war espionage and, while retaining the contemporary setting, the rest of the series reverted to traditional mysteries with a Gothic edge. Probably the best thing that happened for the series (after the chemistry between Rathbone and Bruce, of course) was the arrival of Neill, who directed all but the first of the Universal movies and produced the last nine. Neill gave the series a visual and tonal consistency which helped to disguise the unevenness of the scripts and firmly established the Rathbone-Bruce pairing as almost everybody’s fixed image of the great detective and his companion (even though Bruce’s Watson is very different from Conan Doyle’s, and at times becomes irritating with his foolish bluster). The MPI set includes six fairly informative, though often repetitive, commentaries.

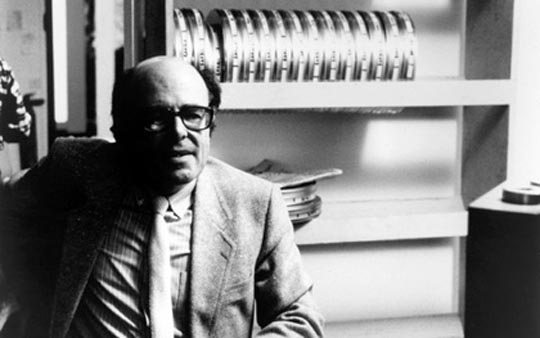

Hotel Terminus (Marcel Ophuls, 1988)

A very different type of detective story is offered by the great French documentarian Marcel Ophuls in Hotel Terminus: The Life and Times of Klaus Barbie (1988), his epic inquiry into the lingering traces of Nazism on three continents. Even longer than his masterpiece on the French Resistance, The Sorrow and the Pity (1969), Terminus never feels over-extended even though the pacing might best be termed “relaxed”. Ophuls’ subject here is not so much (despite the title) Barbie himself as it is the way he is remembered and treated by the various people Ophuls interviewed in France, Germany, the United States and South America. After sketching in the crimes of the “butcher of Lyon”, the sadistic head of the Gestapo in that French city (whose headquarters were located in the Hotel Terminus), Ophuls sets out to trace what happened to him after the war. It’s not a pretty story.

Recruited by U.S. intelligence after the war as a valuable “asset” against the Russians, a man with “excellent interrogation skills” (his victims called it torture), he was eventually spirited out of Europe with the aid of U.S. intelligence and the Vatican, and re-established in Bolivia as a businessman who continued to be involved in intelligence work and political scheming (including a coup or two). Although identified in 1971, it was another 12 years before he was extradited to France, where he was supported by Nazi sympathizers and famous Leftist lawyer Jacques Verges (subject of Barbet Schroeder’s documentary Terror’s Advocate [2007]). What obviously frustrates Ophuls the most is the almost unanimous response he gets from the people he talks to: that was all in the past, let the poor guy live his life in peace, seeking retribution after all these years is distasteful … Not to mention the people who knew him as such a nice, polite boy before the war, and the American intelligence officers who say they find it completely unbelievable that the man could ever have tortured anyone because he was “such a skillful interrogator … he didn’t need to use torture”. Ignoring the fact, of course, that he was a sadist who enjoyed inflicting pain regardless of the need to obtain information.

Robinson in Ruins (Patrick Keiller, 2010)

Not exactly a documentary, more of an essay film somewhat akin to the work of Chris Marker, Patrick Keiller’s most recent work, Robinson in Ruins (2010), is the third part of his unique series delving into the cultural, political and economic state of Britain, following London (1994) and Robinson In Space (1997). In each film, Keillor presents the absent Robinson – an academic who keeps vanishing, leaving fragmentary records of his studies – as a critical voice dissecting the state of the nation. The films consist of beautifully photographed images over which a narrator reads from Robinson’s notes and comments on this “absent friend”. While this may sound like an odd, even awkward, structuring device, it actually allows Keiller to open up his examination, to offer often pointed and contentious observations while also critiquing them, generating a kind of dialogue within the film which extends out to the viewer who has no choice but to actively weigh and evaluate and draw conclusions from what is being seen and heard.

The subject of Robinson In Ruins is Britain after the economic collapse of 2008, and its strategy is to move outward from London along the paths of ancient roads through the countryside, repeatedly running into the remnants of military bases which seem to dominate the landscape. Many of these are U.S. air bases which for decades housed nuclear forces ready to wage war while keeping a distance from the American homeland, a kind of occupation which gave rise to multiple protests over many years. But the larger subject is a more deeply rooted “occupation”, traced back centuries to the days when common lands were first enclosed and turned into private property, a process at least partly predicated on the need to push rural populations into the burgeoning cities where an unlimited wage-labour force was needed to feed the expanding industrial revolution. Ultimately, the economic collapse of 2008 is seen as an inevitable culmination of the myth of the capitalist market, a system deliberately created by political choices and enshrouded in the patently false idea that somehow it’s a natural system over which we have no real control.

Because Keiller is here so concerned with the physical landscape and the sense of historical depth which a single place can embody, he often stops and quietly looks at minute details, letting the narrator’s voice go silent for minutes on end as the static camera observes wildflowers moving in a breeze, animals grazing, and at one point a spider hypnotically weaving its web. The cumulative effect is of a natural world of breathtaking complexity and physical beauty which human society has become blind to in its political and economic striving, a striving which comes to seem artificial and trivial in comparison.

If I have one reservation about the film, it’s that the voice of the late Paul Scofield as the narrator is sorely missed. I’m afraid there are times, all too frequent, when you get the feeling that Vanessa Redgrave is reading the text without really understanding the words, her emphases and cadences scrambling the sense of what she’s saying.

Telling Tales (Richard Woolley, 1978)

Telling Tales (1978) is a surprisingly entertaining formalist feature by Richard Woolley, a British regional filmmaker whose work is informed by feminist and leftist political concerns. In Tales, he offers several parallel, eventually intersecting, narrative threads which illuminate the economic underpinnings of gender relations. Beginning with a middle class couple oh so politely discussing the possibility of divorce because the wife is bored by her inattentive businessman husband, it shifts to the couple’s housekeeper who’s married to a factory shop steward whose union is planning a strike which will have detrimental effects on the middle class couple’s financial position, potentially leaving the wife with a less than satisfactory divorce settlement. But Woolley avoids any simplistic opposition. There are tensions between the working class couple rooted in the man’s resistance to the call for equal pay for the women at the factory – he offers the argument that women don’t need as much money, and that anyway the time isn’t right, they must first fight for the men’s rights, etc. But the women employees force the issue and the union has no choice but to add equal pay to their demands.

The narratives come together when the middle class couple invite the shop steward in for a drink and try to put pressure on him by arguing that employers are struggling as much as the workers and if too many demands are made, the owners will be forced to take their businesses elsewhere and everyone will lose. The businessman suggests that if the union drops the equal pay demand, a settlement can be reached without a strike. The union man is angered by the argument and the businessman’s wife takes over, telling him the story of the factory owner and his personal situation. This is depicted in glossy colour footage in stark contrast to the rest of the film’s rigidly formal black-and-white, accompanied by Abba tunes and presented as a soap opera from which all economic concerns have been banished, focussing instead on a sentimental story about the man’s courtship, happy marriage, and tragedy in the form of his beloved wife’s terminal leukemia. The strike, the woman claims, will be devastating at this difficult time. The resort to emotion undermines the shop steward’s resolve, and it becomes obvious that the businessman’s wife has manipulated him in order to protect her husband’s interests – that, in fact, if the strike doesn’t go ahead and he manages to close a pending deal, she’ll be able to move with him to London, eliminating the “need” for a divorce which would have been economically detrimental to her.

While the film is definitely didactic and the style formal, the quality of the writing and performances breathe life into the arguments and add a great deal of humour.

Comments