In-flight entertainment

I recently took a one-week trip to Beijing to attend my brother’s wedding. The city itself is fascinating, built on a monumental scale (or as dissident artist Ai Weiwei puts it, “inhuman”), and Beijing traffic is one of the most terrifying things I’ve ever encountered. I didn’t have a lot of time to explore, but did manage to take in a trip to the Great Wall, and an afternoon in the Forbidden City (one of 120,000 visitors the day I went; the previous day there had been 130,000).

What I’m writing about here isn’t China itself, though, but the trip there and back … more specifically, what’s happened to in-flight entertainment in recent years. Gone are the days of peering over seat backs to get a look at a small screen at the front of the cabin where some recent Hollywood product was vaguely visible. Now every seat has its own small screen embedded in the back of the headrest in front of it. This touch-screen gives access to a range of material which includes TV shows, news channels, documentaries and movies. Dozens of movies, divided into various categories: Classics, Family, World, Hollywood, Contemporary … even Avant- garde (an odd category which included the documentary Bill Cunningham New York [Richard Press, 2010] as well as the “documentary” POM Wonderful Presents: The Greatest Movie Ever Sold [Morgan Spurlock, 2011]).

Among such new releases as Transformers 3, Pirates of the Caribbean 4, The Green Lantern, Bridesmaids, X-Men 1st Class, etc, there were some interesting oddities and older titles: there were Chaplin shorts from the mid-teens, Hawks’ Bringing Up Baby (1938), Welles’ Macbeth (1948), Anthony Mann’s God’s Little Acre (1958). But despite what the technology (and the 16:9 screen) has made available, for some reason the newer films were all pan-and-scan, which for me makes them unwatchable. Some of the older titles were letterboxed in their correct aspect ratios, so you have to wonder what the people in charge were thinking.

My viewing choices ended up being somewhat random, partly dictated by an aversion to watching on a tiny screen something I really want to see, occasionally interrupted by announcements from the flight crew; partly by curiosity. I didn’t watch all of Michael Winterbottom’s The Trip (2010) because I’d already seen the terrific six-part series it’s culled from and I found the feature version so much less rich, the characters sketchier.

But I did watch all of an HBO special which recorded the Pee-wee Herman Show on Broadway (2011), and it was great to see Paul Reubens back in character as if he’d never been away.

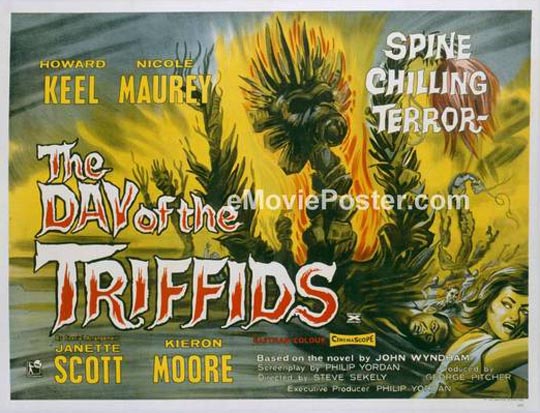

I couldn’t resist watching Steve Sekely and Phillip Yordan’s Day of the Triffids (1963, with additional scenes by Freddie Francis). This appeared to be the same faded transfer that I have on an out-of-print region 2 DVD from 2003. It’s not a very good film, barely scraping the surface of John Wyndham’s apocalyptic novel, but I’ve had a fondness for it ever since I first saw it in the early ’70s at the Avalon Mall in St. John’s, Newfoundland, in a double bill with Frankenstein Meets the Space Monster (Robert Gaffney, 1965).

In a mood to veg, I tried Wolfgang Petersen’s Outbreak (1995), even though I recalled it being not very good (Roger Ebert differs on this point). It’s always amusing to see Dustin Hoffman, one of the most neurotically cerebral of actors, in action mode. Here, he’s rather unconvincing as a military officer specializing in deadly diseases. But the film works fairly well initially as it tracks the introduction of a deadly African virus into the States. Unfortunately, the threat of the disease and the urgent quest for an antidote isn’t enough for screenwriters Laurence Dworet and Robert Roy Pool: they introduce the usual maniacal general trying to protect his insane biological warfare program, even to the extent of trying to destroy the potential cure along with the entire population of an infected town. Hoffman’s climactic aerial showdown with the plane making its bomb run is more funny than suspenseful.

Then there was a mediocre Harry Alan Towers-produced thriller from 1964. Code 7, Victim 5 stars Lex Barker as New York private eye Steve Martin, called to Cape Town by a wealthy businessman who feels his life is in danger. The script by Towers (using his Peter Welbeck pseudonym) and Peter Yeldham has something vaguely to do with Nazis who were in an internment camp in South Africa during the war, but mostly its an excuse for travelogue footage and women in bikinis. The most startling thing about it is seeing Nicolas Roeg’s name in the opening credits as cinematographer. Unfortunately, the battered and washed out print and the pan-and-scan transfer offer little opportunity to judge his work. Only Ronald Fraser seems to be aware of the rubbish he’s in; he obviously enjoyed hanging out on beaches with a lot of well-endowed extras and makes no effort at all to produce a convincing portrayal as the local police inspector. Director Robert Lynn did much better the same year with Dr. Crippen, also shot by Roeg.

I’ve seen and liked many of Anthony Mann’s westerns and film noirs, and even enjoyed his late epics El Cid (1961) and The Fall of the Roman Empire (1964), and the film he died making, A Dandy In Aspic (1968) – but I’d never seen any of his war films. So I took the opportunity to watch Men in War (1957), a taut, underplayed story about a unit cut off in Korea, trying to make their way back on foot to a battalion which may no longer be there. Apparently the military refused any cooperation because they didn’t like the way things were portrayed: the conflicts between Robert Ryan’s quiet, determined Lieutenant Benson and Aldo Ray’s insubordinate, not to mention murderous, Sergeant Montana didn’t represent good military discipline. The Pentagon probably also didn’t like the fact that the film’s senior officer, the Colonel (Robert Keith), is in a perpetual state of catatonia brought on by battle fatigue. There are plenty of good supporting actors who manage to avoid most of the pitfalls of the “platoon movie”, without any overt attempt to offer a fully represented cross-section of American society. But in the end, after a final utterly futile battle which accomplishes nothing other than wasting a lot of lives, the film can’t help but declare its admiration for the fighting man’s heroism, paradoxically endorsing what it previously seemed to be condemning.

And finally, the real discovery of the trip: a small, unassuming western by Alfred E. Green with the cryptic, yet unevocative, title Four Faces West (1948). I started to watch this because it stars Joel McCrea and I stuck with it because its story and characters are thoroughly engaging and its tone quite unusual. McCrea walks into a bank just down the street from where newly elected Marshall Pat Garrett is giving a speech, and very amiably robs the establishment of $2000, being careful to sign an IOU for the amount before taking the manager hostage and riding off into the desert. The bulk of the film is taken up with his journey (on horse and by train) as Garrett and his posse track him. He meets and falls in love with a nurse (Frances Dee) heading west; is observed by a friendly Mexican saloon owner who helps to divert the posse’s attention away from him. And having mailed the money to his father to help pay some debts, he wins some money gambling and immediately sends it back to the bank as a first instalment on his IOU. Gradually Garrett gets a sense that this is no ordinary criminal and he becomes concerned that the men in the posse, eager to earn the reward offered by the bank manager – “dead or alive” – will shoot McCrea rather than arrest him. When he finally catches up with McCrea, it’s because the robber has paused in his run to stop and help a poor Mexican family struck down with diphtheria – he manages to save the lives of the farmer, his wife and two kids and, tired of running, gives himself up to Garrett who has promised to testify on his behalf. The nurse, needless to say, will wait for him.

One of the most interesting things about Four Faces West is the fact that through the entire film, not a single shot is fired. In fact, McCrea even destroys all his bullets to render the gunpowder down into a sulphur concoction for the sick Mexican boys to breathe in. The film has a lightness and charm which would make it a fitting companion for Jacques Tourneur’s The Stars In My Crown (1950), in which McCrea lays down his guns in order to bring a peaceful sense of community to a small town in the years after the Civil War.

If my flights had been longer, there were plenty of other movies to see – and some of them no doubt would have been better choices than a few of those that I did watch. But they’ll have to wait for the next trip.

Comments

The first time I experienced the new, expansive inflight entertainment, I left grumbling that my 15 hour flight to Australia didn’t allow me to finish my 6th movie.

One of the drawbacks of too much choice … you inevitably feel that you should probably have chosen something else to watch. Probably an insidious plot by the airlines to make us all more frequent fliers!