In the beginning …

I recently started work on a documentary about the history of movie theatres and movie-going in Winnipeg. A brief article about the project in the Winnipeg Free Press has brought an amazing number of calls and emails from a wide range of people who have quite passionate memories of the old neighbourhood theatres and the downtown picture palaces. (I even got a call from a 90-year-old gentleman who recalls the first movie he saw: at age 5 in 1926 his parents took him to see Ben-Hur [Fred Niblo, 1925] at Shoal Lake, Manitoba.)

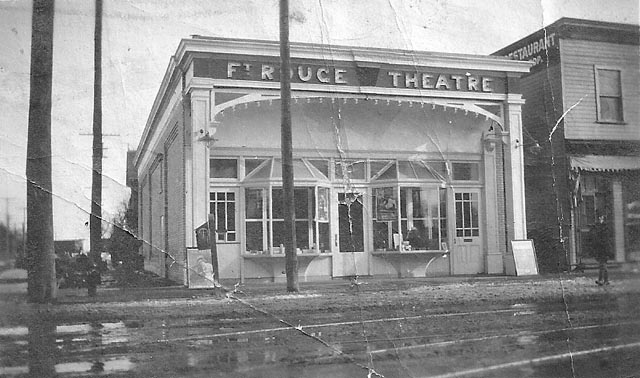

I’m just getting going on the background research, and spent a couple of hours the other day at the City of Winnipeg Archives where I found some fascinating documents in the city council records. For instance a letter from the Chief Constable to the Mayor about attendance at “moving picture theatres” at 9:00 PM on the night of Saturday, November 29, 1913:

“As per your phone request to a member of my staff on the night of Saturday, the 29th Inst., I beg to report for your information that at 9 p.m. the two Picture Houses in Fort-Rouge had an audience totaling 570 persons. The North End Division, which includes everything North of the C.P.R. Railroad, reports at the same time having a total audience at Picture Shows of 1475 persons. The Central Division, which includes all that part of the City of Winnipeg between the Assiniboine River on the south and the C.P.R. Railroad tracks on the North report at the same time having a total attendance at Moving Picture Shows of 11,200. The District of Weston, in which there is one Moving Picture Show located had on Saturday, the 29th Inst. 350 persons in attendance, being a total number of 13,595 attending Moving Picture Houses at that time.”

I was surprised by the number, as this was only a few years after the first dedicated movie theatres had started to be built.

In 1913, the theatre owners sent a joint letter to the council requesting that theatre operators be licensed; this would mean that training, testing and official qualifications would have to be obtained before anyone could open a new theatre.

In 1919, the owners wrote requesting license fee relief because the city had forced all theatres to close for six weeks during the flu epidemic, causing a serious loss of income for both owners and employees. The Market, License and Relief Committee regretted that they couldn’t waive part of the fees for the relevant period.

From 1920, there were by-laws and regulations for the handling and storage of nitrate film (including blueprints for the design of film cans and metal cabinets for stacking them in). A letter from the theatre owners’ association on November 21, 1923, complains that Winnipeg is the only city in the country which levies a “vault tax”, supposedly to cover the cost of inspections of the storage facilities, on top of the regular business tax.

What I found most interesting, though, was a series of documents pertaining to censorship, starting as early as 1912. There were three censors, each having the task of visiting the film exchanges to view prints and make judgements, cutting out anything deemed unfit or offensive. If the distributors disputed a decision, a second censor would take a look and either agree with the first, or reverse the decision.

By 1915, the number of exchanges had increased from 3 to 10 and the system had become unwieldy; the fee was increased from $1 per reel to $1.25 in order to finance the purchase of the censors’ own projector. From then on, prints would have to be sent to the censors for judgement (a system which is still in operation, although the Film Classification Board no longer censors, merely rates).

In April 1915, Winnipeg’s censors amalgamated with those from Saskatchewan, forming a regional standard. And in 1916, under the influence of the Council of Women, the first female censor was appointed to the board.

In the censors’ monthly report for April 1915 (filed on May 1), they passed 548½ reels and condemned 53½. The complaints ranged from burglaries, murders and suicides to blasphemy.

In a letter from May 21, 1912, seven theatre owners filed a complaint:

“It is the practice by the city censors to attach together all portions of films which have been censored and which have been found objectionable in any way, into one film. These are exhibited, we are advised, in a local theatre, before a large mixed audience. Every objectionable picture censored, such as suicides, murders, and other objectionable features are exhibited together. This has a very deleterious influence upon every person who is not familiar with the moving picture business; unless they are acquainted with the circumstances, they may form the impression that the exhibition of these censored pictures is a regular exhibition of moving pictures. This creates a very bad influence and, after such an exhibition, the average person would not care to witness a second performance.”

It’s not clear who was passing this censored material on to a particular theatre, but it is clear that the owners were not overtly against censorship itself, just concerned with the public image of their business.

Best of all, however, was a letter to the committee from License Inspector Frank Kerr on May 22, 1912. Mr Kerr reported in detail on three disputed films (original spelling throughout):

“Myself in company with the two Picture Censors, Mr Bevington and Mr Horne, attended at the Princess Theatre on the morning of the 18th inst, when three films rejected by Mr Horne and being the ones regarding which the General Film Co made the appeal, were shown to us. After viewing these films Mr Bevington and myself fully concurred in the view that Mr Horne had taken of said films and therefore endorsed his rejection of the same.

The following is an outline of the subjects depicted by the said films and the objectionable portions contained therein.

The Chocolate Revolver. Vitagraph Co

A man buys his little daughter an immitation revolver made of chocolate and shows her how to hold him up. He then leaves the house with his wife for the evening, and their servant, as soon as the child is asleep, also goes out.

Two burglars enter the house through the window and one of them upsets a statue which awakens the child, who gets out of bed and goes downstairs and is held up at the point of a revolver by one of the burglars. He tells her to go ahead of him upstairs and show him where her mothers jewels are kept. She leads him to a cupboard and tells him they are hidden there, while he is looking for them she closes the door and locks him in. She then goes to her room and gets her chocolate revolver and goes downstairs where she surprises the other burglar who is wrapping up the silver. She holds him up and telephones to the Police. While off her guard he seizes her and grabs her chocolate revolver. He then ties a handkerchief round her mouth and stuffs her under the sofa. Meanwhile the Police enter and are in their turn held up by the burglar and made to go into a room and are locked in there.

The father and mother shortly after arrive and enter the room and are also held up; however the little girl gets out from under the sofa and opens the door of the room where the Police are. They come out and capture the burglar. They then proceed upstairs and the girl opens the cupboard door in which she had locked the other burglar. He is also captured.

Objections

Burglary and too much use of a revolver. Rough handling of a little girl.

Indian Romeo and Juliet. Vitagraph

Chief of a hostile tribe enters enemies country and makes overtures of peace. He meets the daughter of the chief and they fall in love and are secretly married. The next day her father tells her she is to be married to one of her own tribe. She goes to the medicine man who is in the secret and favourably inclined towards her, and he gives her a sleeping draught, so that she will appear to be dead. She is taken to the burial ground and there her husband finds her and mourns over her not knowing that she is only asleep. The rival Indian comes along and they fight with knives when the husband kills the rival. He then kills himself with his knife and falls across the body of the girl, who awakened by the shock and finding her husband dead, also commits suicide.

Objections

Indians insufficiently dressed, use of knife and two suicides.

Marriage or Death. Pathe

A family of settlers are visited by a Morman who is desirous of marrying the daughter, who is engaged to another settler. He is refused and goes away. The settlers are warned by a friend that the Mormans are angered at her refusal and are determined to take the girl by force. The Mormans obtain the aid of a tribe of Indians, and they at once make for the settlers home, who in the meantime have left as a result of the warning. A chase ensues in which some of the settlers are killed and the girl captured and taken to the Morman settlement, where she is shown a knife and told that she will either marry the Morman or have her throat cut. She refuses and just as the knife is being raised to kill her a band of settlers, who have been collected by the girls lover, arrive and shoot the Mormans and rescue the girl.

Objections

White men getting Indians to help against white men. Abducting a girl. Using a knife to suggest cutting throat. Raising the knife to kill girl.”

The social attitudes exposed by the objections to this last film are particularly interesting. The censors were not bothered by the demonic depiction of Mormons, but obviously troubled by the idea that Indians might be recruited to fight white settlers.

*

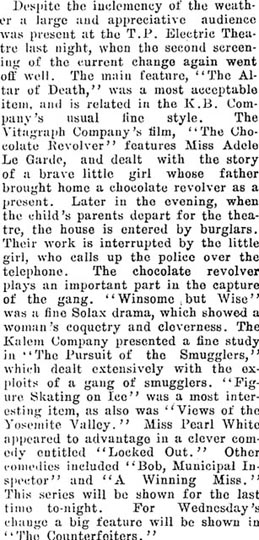

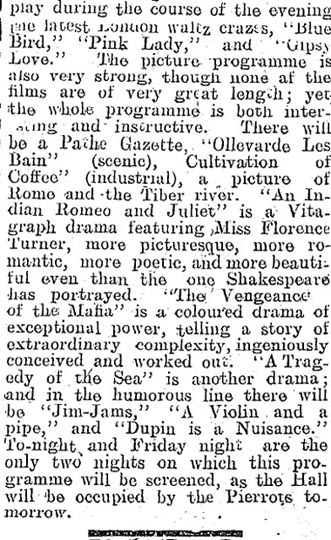

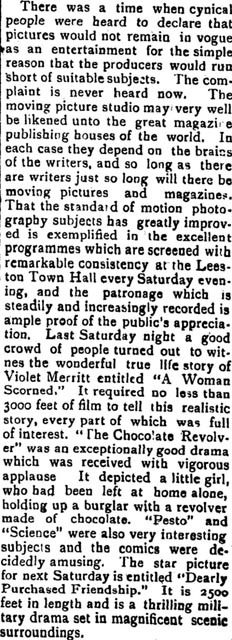

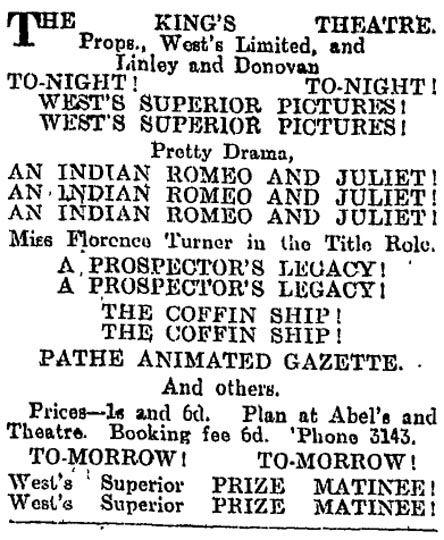

Apparently not everyone had the problems with these films that the Winnipeg censors did. The clippings included below are from a remarkable website put up by the New Zealand government which archives 68 different periodicals from 1839 to 1945, and it seems that downunder, people really liked these movies. According to the Feilding Star of July 17, 1912, An Indian Romeo and Juliet is “more picturesque, more romantic, more poetic, and more beautiful even than the one Shakespeare has portrayed,” while the Ellesmere Guardian for November 26, 1913, said that The Chocolate Revolver is “an exceptionally good drama which was received with vigorous applause.”

The Chocolate Revolver (Vitagraph, 1912) starred Adele DeGarde as the girl; she seems to have had a remarkably prolific career (IMDb lists 114 titles) which spanned only 10 years, from 1908 to 1918. She apparently retired from movies at age 19.

An Indian Romeo and Juliet (Vitagraph, 1912) was directed by Laurence Trimble in 1912, with stars Wallace Reid and Florence Turner. IMDb lists 101 titles for director Trimble between 1910 and 1926. Reid has 216 titles listed for the 13 years between 1910 and 1923; he died on January 18 of that year at age 31. Florence Turner’s career spanned from 1907 to 1943, with IMDb listing 184 titles.

Interestingly, Marriage or Death (1912) was produced by the French company Pathe Freres, but I haven’t been able to find any information about cast or crew.

Reviews and advertisements for these films culled from various New Zealand newspapers:

Comments

Good stuff.