Lionel Rogosin: part two

Lionel Rogosin is generally referred to as a documentary filmmaker. He himself rejected the label, saying several times in the documentaries accompanying the three features in the Carlotta DVD set that he saw himself following in the steps of Robert Flaherty and De Sica, constructing dramatic neo-realist narratives out of real situations. While there is unquestionably a documentary element in both On the Bowery and its follow-up Come Back, Africa (1959), Rogosin nonetheless uses invented stories and non-professionals performing versions of themselves in order to illuminate social conditions and issues which concerned him.

In the late ’50s, Rogosin went to South Africa with his wife and a very small crew, determined to do what he could to expose the evils of apartheid. Naturally, this was something he couldn’t do openly. He managed to connect with Myrtle and Marty Berman, white activists who were working against the regime, and eventually found himself among the African journalists who put out the magazine Drum. Declaring that he was there to serve their needs, he worked with two of the journalists – Lewis Nkosi and Bloke Modisane – to create a story about a black worker from Zululand who faces all the difficulties the regime threw at Africans.

Zachariah Mgabi has left his home to seek work. Initially, he’s exploited at a mine where the pay is so meagre that he has to write home to ask his wife to sell a couple of cows so he’ll have enough money to get back to her; then he moves on to Johannesburg for a brief stint as houseboy for a middle class white couple, a job that ends quickly because of the shrieking petulance of the wife (played by Myrtle Berman) who has nothing but contempt for “natives”. Other jobs follow, and Zachariah’s wife Vinah arrives with their children, joining him in the vibrant slum of Sophiatown. Unable to hold onto a job, constantly faced with the threat that his permit to live in the city will expire, and intimidated by local gangsters (the “tsotsis”), Zachariah founders; Vinah wants to find work as a domestic, but he’s adamant that she stay home to look after the children.

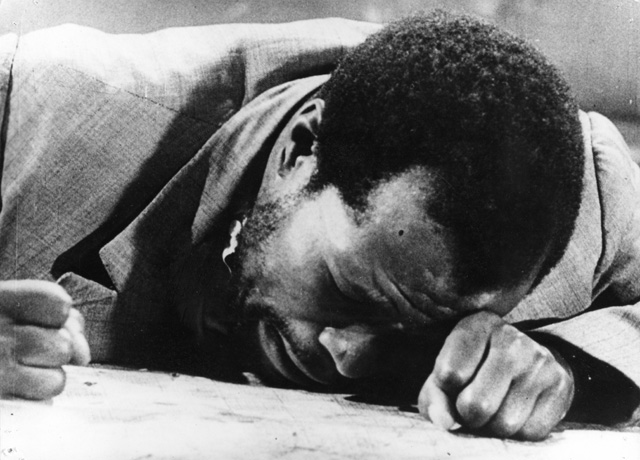

He spends time at a local, informal meeting/drinking place, where intellectuals (actually the writers from Drum) discuss and argue the political situation, anger fed by repression. But any kind of real change seems at best far in the future. During a night raid, Zachariah is arrested and while he’s away, the local tsotsi thug Marumu attacks Vinah. Returning from custody, Zachariah finds her body in their hovel and the film ends with a wrenching howl of despair …

Made using subterfuge, Come Back, Africa lacks the visual and formal elegance of On the Bowery. Rogosin had to convince the authorities that he was making a travelogue, and the film has lengthy sequences shot on busy streets, focusing on groups of musicians performing for passersby. The effect is to suggest a vibrant black culture still thriving beneath the boot-heel of white supremacy, but the main thrust of the narrative is towards that deep endnote of despair.

Once again, Rogosin won an award at the Venice Film Festival, and Come Back, Africa was instrumental in raising awareness outside of Africa about the appalling conditions which existed under apartheid.

*

For his next film, Good Times, Wonderful Times (1965), Rogosin scrapped even the minimal neo-realist narratives which had anchored his first two films. Neither drama nor documentary, this is pure polemic. Wanting to make a “peace film”, the director discovered that even liberals in the States considered such a project anti-American; so he went to England to make it.

The structure is unsubtle, but the cumulative impact is quite powerful. At a trendy middle class party, amidst the dancing, drinking and jazzy music, we overhear scraps of conversations in which the various characters offer opinions about war and violence, spurred on by questions by the closest thing the film has to a protagonist, Molly Parkin, a young woman who tries to get at what it is that makes men want to go to war. The shallow, complacent responses she gets from the party-goers trigger montages of documentary material – images of fascism, atomic bombs and their impact on Japanese civilians, the horrors of World War One and the Holocaust – gradually leading to the Ban-the-Bomb rallies in London, the march to Aldermaston, speeches by Bertrand Russell, and finally Martin Luther King giving his “I had a dream” speech at the civil rights march on Washington in 1963.

Rogosin and his collaborators spent several years digging up the archival material used in Good Times, Wonderful Times, and despite a certain obvious crudity in the juxtapositions of middle class privilege and the very real horrors which result from the kind of complacency which accepts that “wars are inevitable”, the film is often quite powerful. When a cheerful Chelsea pensioner talks about his military experiences in World War One (giving the film its title), he urges a younger man to put his son into the military to “make a man of him” – at which point Rogosin cuts to a crowd of bright-faced Hitler Youth cheering in adoration of the Fuhrer. The impact of the cut is too shocking to be seen as ironic … and in fact the entire film avoids any whiff of irony, that over-used device which negates meaning and defuses anger by turning every issue, no matter how serious, into mere amusement.

As with the On the Bowery disk, these two features are both accompanied by excellent documentaries by Rogosin’s son Michael about the making of the films, as well as DVD-ROM text files, including complete transcripts. The African dialogue in a number of scenes in Come Back, Africa has only French subtitles, but the sense of what is being said is always clear. This French box set is a terrific introduction to an important, yet not widely known, filmmaker. Although apparently now out of print, it can still be found at various places on the Internet, and is definitely worth seeking out.

Comments

Milestone Films will be releasing COME BACK, AFRICA in DVD and Blu-ray this summer with new English intertitles. Included will be Lionel’s fourth feature film, BLACK ROOTS (also restored by the Cineteca di Bologna) that has never been available on video before. There’ll also be a lot of bonus features including Michael Rogosin’s “making of” documentaries for each film and Jürgen Schadeberg’s HAVE YOU SEEN DRUM RECENTLY?