Stanley Kubrick 2: The Business – Spartacus (1960)

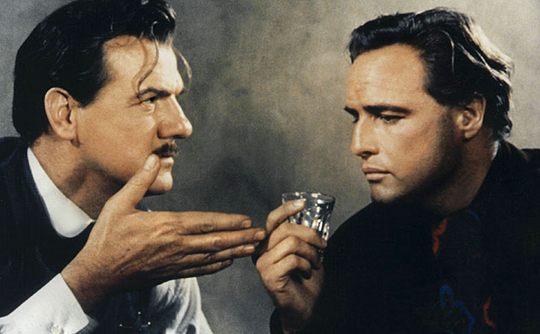

I’ve been hung up for a few weeks in my plan to re-watch all of Stanley Kubrick’s films in chronological order because the prospect of sitting through Spartacus one more time was a bit daunting. There was a three year gap between the success of Paths of Glory and this, the biggest production of Kubrick’s career. He had tried to get a number of things off the ground, and had worked for a while with Marlon Brando in preparation for One-Eyed Jacks. He and Brando had some proverbial “creative differences” and Brando, the producer, fired Kubrick and decided to direct that western himself.

Ironically, Kubrick’s next movie came to him when the original director, Anthony Mann, was fired after a week of shooting. Kubrick’s Paths partner, Kirk Douglas, called on him to come in and rescue the epic. Apparently there were a lot of creative differences there as well and Kubrick and Douglas fought throughout the production and parted no longer friends. It didn’t help that Kubrick publicly distanced himself from the finished film.

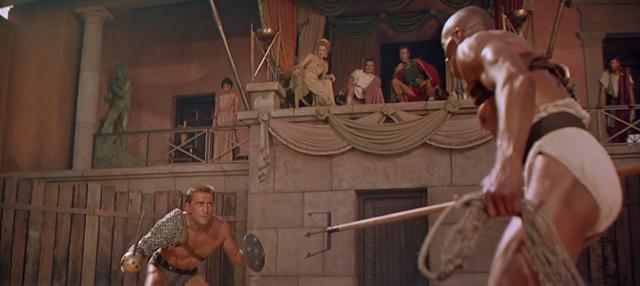

Spartacus (1960)

Not surprisingly, Spartacus (1960) shows few signs of the Kubrick personality that can be discerned in his other films. This was his only job-for-hire and it was one of those gigantic Hollywood productions which offer little room for personal creativity, requiring of its director logistical rather than artistic talents. In this respect, Kubrick acquitted himself well. Logistically, Spartacus is an impressive achievement. But creatively, it’s ponderous, dramatically uneven, visually erratic (in high-def, the in-studio exteriors are even more jarringly mismatched with the epic landscapes, and surely Jean Simmons was attractive enough not to require those vaseline-soft close-ups). You can tell when Kubrick is interested and when he’s just getting the job done.

The sincere, occasionally preachy, script by Dalton Trumbo hits most of the usual historical epic moments, but only comes alive in some of the supporting performances and tangential details. In particular, you can feel Kubrick enjoying the opportunity for comedy afforded by Peter Ustinov’s slave-trader and gladiator-school-owner Batiatus (Ustinov gets away with a few moments which seem improvised) and by Charles Laughton’s ripe senator Gracchus. One of the most interesting scenes (originally cut from the movie and reinstated in Robert Harris’s restoration) is the one-shot encounter in the bathtub between Laurence Olivier’s sexually ambiguous Crassus and his body-slave Antoninus (Tony Curtis) – “do you prefer oysters or snails?” And I kept expecting Nick Dennis’s Dionysus to give an energetic “va-va-voom” every time he opened his mouth.

Spartacus is best in the early stages, the Libyan mines (Mann’s work) and the gladiator school. After the initial slave revolt, we get repetitive scenes with Spartacus trying to lead his growing army to freedom while the senators back in Rome bicker, with Crassus using the rebellion as a means to establish himself as dictator. It all feels very long, with some occasionally striking visuals in the rebel camp and a couple of large-scale battle scenes. Even while watching it, I knew that I’d never want to return to it again. (Ironically, Anthony Mann’s subsequent features El Cid [1961] and The Fall of the Roman Empire [1964] show that he had a far greater affinity than Kubrick for the epic style.)

As with most such gigantic Hollywood movies, the relentless score (by Alex North, Oscar-nominated of course) seems to be determined to beat the viewer into submission. North would later write an original score for 2001: A Space Odyssey, which Kubrick ditched in favour of the now familiar eclectic collection of classics. I used to have a cassette of North’s music for 2001 and I recall that it had the same kind of bombastic tone as his score for Spartacus; Kubrick was wise not to use it.

Less than a hundred years after the end of slavery in the U.S., Hollywood found it necessary to go back 2000 years to make a statement against the insidious institution. Imagine these resources being put in the service of Nat Turner’s rebellion! But then, of course, the slaves wouldn’t have been white and that would have presented a lot of unwanted problems.

One-Eyed Jacks (1961)

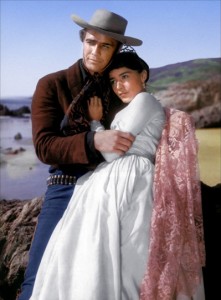

By coincidence, I’ve just obtained a German Blu-ray of One-Eyed Jacks (1961), a decent if rather pale transfer from a French print. I’ve waited a long time for a watchable copy of this old favourite and I wasn’t disappointed. The script by Guy Trosper and Calder Willingham (co-writer of Paths of Glory) was based on a novel by Charles Neider, who had been born in the Ukraine. It has a flavour different from most westerns of its time (and earlier), hinting like Robert Aldrich’s Vera Cruz at spaghetti westerns to come with its Hispanic settings and morally compromised characters. Betrayed by his partner Dad Longworth (Karl Malden), Rio (Brando) escapes from a hellish Mexican prison and tracks the older man down to Monterey, where he’s now a respected family man and sheriff. As part of his planned revenge, Rio seduces Dad’s step-daughter Louisa (Pina Pellicer, a Mexican actress of great charm who died at 30 just a few years after this film), only to realize that he’s actually fallen in love with her.

The moral failings of both characters give the film a weight that approaches tragedy, though Brando later claimed that the studio cut had over-simplified things, making Dad and Rio too black-and-white (his own cut was supposedly about five hours long). Dad’s guilt at his betrayal of Rio drives him to a self-righteous frenzy, intent on destroying the man he wronged in order to erase the crime; instead, of course, he just provides more justification for Rio’s revenge and brings disaster on himself.

Brando’s direction is functional and stylistically unadorned, focused on the characters and themes, letting the great desert and seacoast locations take care of the atmosphere. You can’t help wondering what Kubrick might have made of this story; the two characters and their mutually destructive flaws must have appealed to him. This material seems much more suited to his outlook than the liberal finger-wagging of Spartacus, and the western was the only major genre he never tackled (later, in A Clockwork Orange, he would even briefly touch, in an oblique way, on the musical).

Comments

Very oblique.

Everything in this article is quite reasonable. Compared to anything else Kubrick was involved in, Spartacus is ponderous and predictable. As stated there are a few shots that are unmistakably sharp-eyed Kubrick. That being said, it is still head and shoulders above other examples of the “I’ve just returned from Rome” genre of the day and before, with the exception of the silent Ben Hur.

At the risk of being a shameless self-promoter, I’m really writing here to tout my documentary that illustrates how and why Kubrick was a master filmmaker. The title is Paths of Glory: Anatomy of a Film. Website: http://www.anatomyfilm.com. It is currently raising finishing funds on Kickstarter.com:

http://www.kickstarter.com/projects/1149150329/paths-of-glory-anatomy-of-a-film

Happy New Year to one and all!