Discovering Theo Angelopoulos

Film festivals create a peculiar psychological space, lifting you out of “reality” and immersing you in a subjective world where what you see up there on screens in dark auditoriums becomes more important than anything else – even eating and sleeping seem to become irrelevant.

The Toronto International Film Festival

Having lived mostly in Winnipeg for the past 39 years, I haven’t had a lot of opportunities to go to film festivals, but I’ve been to the Toronto International Film Festival twice. The first time was for a few days in 1992 when a short film I made with ten other directors was shown. I saw thirteen movies in about five days, starting with Guy Maddin’s Careful (1992) and ending with Quentin Tarantino’s Reservoir Dogs (which I despised). The high points were Juzo Itami’s satirical comedy Minbo: The Gentle Art of Japanese Extortion (1992) and Alex Cox’s Mexican masterpiece El Patrullero (Highway Patrolman, 1991). I actually got a chance to chat with Cox in a hotel lobby and we had a brief conversation about his other masterpiece, the misunderstood Walker (1987).

My second time at TIFF was in 1998. This was one of the perks I got for attending the Canadian Film Centre’s program for editors that year (and even went some way towards compensating for an otherwise frustrating and unsatisfactory experience). I saw approximately 30 movies in ten days (most at press screenings as the CFC gave us industry passes). In fact, I think the only public screenings I attended were Jonathan Rosenbaum and Walter Murch’s reconstruction of Orson Welles’ Touch of Evil (1958) and a gloriously restored print of Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger’s The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp (1943), the first time I’d had an opportunity to see it. My biggest regret was not getting a ticket to go to John Waters’ presentation of Joseph Losey’s famous camp epic Boom! (1968).

The high points, apart from Blimp and Touch of Evil, ranged from Thomas Vinterberg’s Festen (Celebration, 1998), still the finest expression of Dogme 95; Walter Salles’ lovely Central Station (1998); Wes Anderson’s Rushmore (1998); and Theo Angelopoulos’s Eternity and a Day (1998). Of all the people I encountered who had seen the latter, I seemed to be the only one who liked it. The joke was generally that the slow-moving film in fact seemed to last longer than eternity. I was enthralled, immersed in Angelopoulos’ flawless evocation of the ways in which memory shapes experience and, subjectively, blends the present moment with past experience. And, of course, it starred the great Bruno Ganz as a dying writer whose mind drifts over the events of his life as an unforeseen circumstance forces him to take a final action in the world he’s about to leave, unwillingly becoming responsible for a young, lost Albanian boy with whom he undertakes a physical journey which parallels his subjective mental/temporal journey.

Encountering this film by Angelopoulos was significant for me because it connected my TIFF experience with the first festival I’d ever attended. That was in Hong Kong in 1981, where I saw almost 60 films in 16 days at the 5th Hong Kong International Film Festival, including four by Angelopoulos.

5th Hong Kong International Film Festival, 1981

I approached the 5th Hong Kong International Film Festival like a military campaign. The screenings were at several different sites, so armed with a city map and the festival schedule, I calculated times and distances and about two weeks before the festival began, I created a schedule for myself and bought all the tickets in advance. Of course, I had to allow brief breaks for meals, but for most of the festival’s two week run, I intended to be in theatres watching movies. I made sure to carry a notebook with me and after each screening, I would quickly scribble my impressions and reactions to what I’d just watched – a prescient thing to do because otherwise, by the end of the festival, I would have had no memory of what I’d seen in the early days. Then, when it was all over, I fleshed out my notes and typed them up into a 56 page critical journal, concluding with my thoughts on the four films by Angelopoulos.

Now, thirty-one years after the festival, Artificial Eye in England are issuing the complete works of Theo Angelopoulos on DVD in three box sets – I already have the first two, and the third is due out February 13. The early films that I saw in Hong Kong were a revelation – a master director with an incredible ability to evoke the subjective experience of time while also creating a powerful sense of the material reality of history, the complex social and political webs within which individual lives are lived. While I haven’t seen a lot of his later films (and found Ulysses’ Gaze [1995] unbearably tedious), I’m eager to revisit the work that so impressed me in 1981. And after watching the films, I’ll go back to that journal and compare my current impressions with those earlier thoughts.

Theo Angelopoulos’s debut feature, Reconstruction (1970)

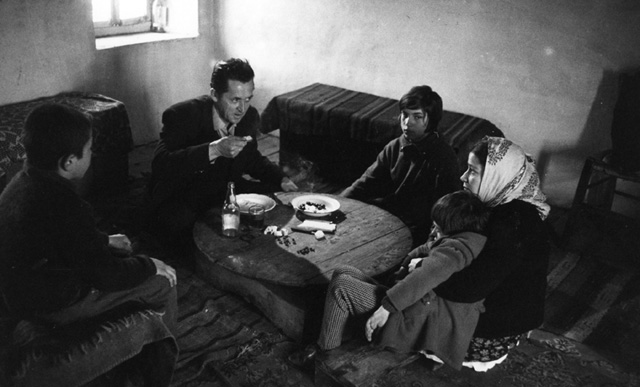

But first, I’ve just watched his debut feature, Reconstruction (1970). While the four films that followed this presented an epic meditation on 20th Century Greek history (from a leftist viewpoint), this first feature is smaller and more personal, though already stylistically assured and confidently playing with narrative time as it deals with the investigation of a crime in a remote village, the events leading up to the crime, and the conflicting stories of the two perpetrators, each attempting to shift the blame to the other.

The film begins with the return of migrant worker Kostas Gousis (Mihalis Fotopoulos) after years away in Germany. His youngest child doesn’t even know who he is. Then, after the opening titles, the film jumps ahead to an attempt by police to reconstruct the events surrounding Kostas’ death, interrogating his wife Eleni (Toula Stathopoulou) and, eventually, her lover, the gamekeeper Hristos Gikas (Yannis Totsikas). Angelopoulos circles around the event without ever actually showing it, merely depicting the conflicting narratives offered by the couple, intercut with their elaborate scheme to lay a false trail of evidence indicating that Kostas had once again left the village looking for work in Germany.

But in such a small village, no secret can remain unexposed and there’s a grim sense of inevitability which Eleni and Hristos themselves seem to feel right from the start. The murder has no chance of restoring the relationship they had before Kostas’ return and yet they’re driven to commit the crime anyway. Their own movements in laying the false trail expose them. Everyone in the village, knowing of the relationship, immediately suspects the couple; Eleni is visited by her brother who simply demands that she tell him how Kostas was killed.

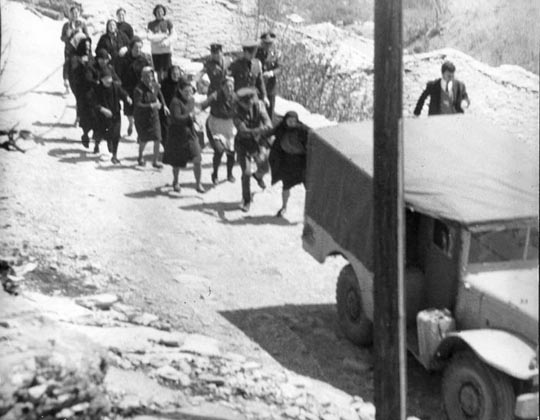

Visually, the film is weighed down by shades of grey, drenched in endless rain and mud, which takes on the feeling of the social and historical constraints which trap and eventually crush the characters. The grim, fatalistic tone reaches its climax at the end as Eleni is being led away by the police and a shrieking crowd of village women attack her, laying the full blame for the murder on her and her unrestrained sexuality, in retrospect revealing the roots of the crime in a society which demands, as an essential component of social order, the repression of female sexuality.

*

In looking up information about Angelopoulos, I just came across an interesting blog called Cinephile written by Matthew Thrift in England. He has a recent interview with the director and an interesting review of the first volume of Artificial Eye’s Angelopoulos Collection.

Comments

Tried watching Ulysses’ Gaze–with the ubiquitous Harvey Keitel–and was endlessly distracted by his presence. Perhaps, he deserves another look (Theo, not Keitel).

Also, just to interject, Idioterne is the best Dogme film, you spass!

Dogme is in the eye of the beholder, I guess.

And, yes, my biggest problem with Ulysses’ Gaze was Harvey Keitel … not the right actor for the film.