Nuclear Madness

It’s probably difficult, if not impossible, for someone born in the last 20 or 30 years to understand the psychological atmosphere that prevailed at the height of the Cold War when the two superpowers were locked in a policy appropriately designated MAD – mutually assured destruction. The idea was that war could only be avoided by the stockpiling of devastating weapons; each side knew that if they tried to start a war, both sides would be obliterated in the ensuing nuclear exchange. (Although it’s hard to believe that intelligent people could subscribe to such an idea, that kind of thinking is actually still alive and well, at least in the States, where the powerful gun lobby continues to insist that everyone will be safer if everybody is armed.)

The reality of MAD reached its pinnacle during the Cuban missile crisis in October 1962, during which Kennedy and Khrushchev faced off in a macho showdown over the USSR placing missiles in Cuba, too close to the US for anybody’s comfort. I suppose the fact that the Soviet Union finally did back down might be seen as proof of the effectiveness of MAD, but at the time all it did was make everyone more paranoid and insecure.

That paranoia gave rise to a number of books and movies about “accidental” nuclear war, the idea that even if those in charge had the very best intentions and were capable of making rational decisions about the use of nuclear weapons, some inadvertent, unforeseen event could set the whole thing off unintentionally. The best known movies, of course, are Stanley Kubrick’s Dr. Strangelove (1964) and Sidney Lumet’s Fail-Safe (also 1964).

But the actual experience of nuclear war was a trickier subject. The ’50s had seen a minor sub-genre of post-nuclear movies, mostly about a handful of survivors either fighting among themselves for limited resources or battling radiation-caused mutants. Stanley Kramer came out with the sombre On the Beach (1959), in which survivors in Australia simply wait for the fallout to reach them and put an end to their middle class lives, and later – after the Cold War had eased up and the sense of imminent danger had faded somewhat – there were a few movies about the actual experience of nuclear attack: in the U.S., Lynne Littman’s Testament (1983) and Nicholas Meyer’s The Day After (1983), and from England the much harsher, more realistic Threads (Mick Jackson, 1984).

Despite the fact that there was clear evidence of what would actually happen if nuclear war did occur – Hiroshima and Nagasaki left no doubt about the effects – official sources insisted on downplaying the consequences. The Atomic Cafe (1982) effectively skewered the propaganda disseminated by the US Government to make the idea of nuclear war to some degree “acceptable”, by combining documentary footage of actual bomb tests (displays of technological strength to reassure the population) with the familiar civil defence instructions about hiding behind your couch or under your classroom desk and putting your hands over your head to protect yourself against the blast.

While that kind of propaganda merely looks ridiculous now, the BFI’s latest collection of films from the vast library of the Central Office of Information, Volume 6: Worth the Risk?, contains something more chilling. The Hole in the Ground (1962) is a half-hour “docu-drama” about the work of the United Kingdom Warning and Monitoring Organisation, a national network of professionals and volunteers which had been set up by the government to gather information in the event of a nuclear attack. Established in 1957 and remaining in service until 1992, the UKWMO had something like 1500 monitoring stations spread all over Britain, each feeding information into a number of centres where the data could be collated to provide a picture of the attack – the location, number, and size of the strikes, weather patterns and how they affected the spread of fallout – and from which instructions could be sent to local civil defence units for management of the population in the aftermath.

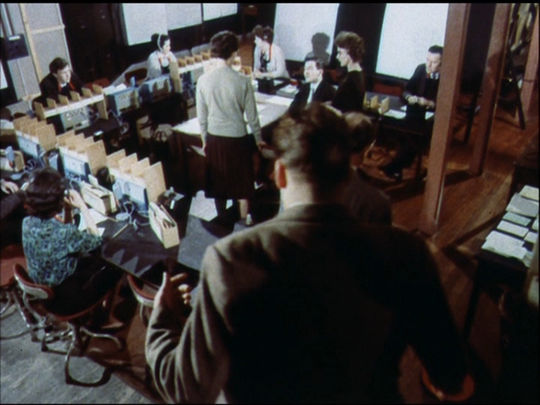

What makes The Hole in the Ground (produced by RHR Productions and directed by David Cobham) so chilling is the veneer of rationality it presents. Everyone involved – the observers in the field, the technical experts, the civilian staff manning the phones – remains calm and focused as the attack takes place. The film emphasizes the process of information gathering without ever acknowledging what that information represents in terms of the actual devastation of cities and towns. It’s all about the numbers. The only elements of “drama” offered by the film are a brief journey outside an observation post to fix a downed phone line (the sole indication that communications might be interrupted in any way) and the moment when one of the operators in the bunker hears that her parents’ home town has taken a direct hit. For the rest, it’s all about calm, businesslike procedure.

Here we have a portrait of the technocratic mentality which can so compartmentalize experience that it’s capable of shutting out the horrors of nuclear war while it focuses on an immediate abstract task, in the process seeming to normalize the unimaginable horror represented by the data being compiled on the elaborate charts in the bunker. The overt purpose of this film is to lull viewers into accepting that nuclear war is merely a set of technical issues to be dealt with calmly and rationally by the experts. What’s left out is the nightmare experience most of those viewers would actually be undergoing while these serious-minded bureaucrats do their job.

Seeing this short film has made clearer to me just what Peter Watkins was attacking in his brilliant faux documentary The War Game (1965). That film, which on the surface calmly depicts the actual effects of a nuclear attack on ordinary people in Britain, was commissioned by the BBC, but never aired because it was considered too inflammatory. Of course it was inflammatory – the only rational response to the official mindset so clearly revealed in The Hole in the Ground would be anger and outrage. The official suppression of Watkins’ film shows that those in charge knew full well that the view presented in government propaganda was a lie and that they needed to maintain public ignorance in order to keep control.

It’s also tempting to imagine that Stanley Kubrick saw The Hole in the Ground at some point because so much of Dr. Strangelove reflects the film’s attitudes, but pushed to extremes which reveal the complete insanity behind the cool facade. (Also, interestingly, this propaganda film opens with the overture from Richard Strauss’s Also Sprach Zarathustra, which Kubrick would use six years later as the opening theme of 2001: A Space Odyssey.)

Comments

This is a fascinating topic. Thanks for this post.

For many years I discussed ‘fears’ with my grade 12 English students as part of a major project. Several years during the 1980s the biggest fear among students was the nuclear war issue. I think for at least a couple years the majority of my grade 11 and 12 students didn’t think the world would exist much longer as we know it, because of nuclear destruction.

By the mid to late ’90s this fear almost seemed to evaporate. Likewise, hasn’t the issue almost disappeared from cinema the last 15 -20 years?

If so, I don’t know why.

Has the situation improved that much in recent years? Don’t the U.S. and Russia still have huge, aging stockpiles? Isn’t it getting easier for more players to join the nuclear club?

Cheers….keep your precious bodily fluids replenished.

I’m what you might call a water man, Grant …

I think what you say is probably mostly due to the collapse of the Soviet Union and a global politics based on that bi-polar superpower system. That produced an illusion of the disappearance of the threat, when in fact things are probably more dangerous now. As insane as MAD was, it did impose a kind of political stability when it came to nuclear arsenals. Now of course, those weapons are scattered all over Eastern Europe without the kind of supervision the Soviets had imposed, and there’s been a lot of trading in materials and information among various governments and non-governmental factions … plus of course other countries have been developing nuclear capabilities (Iran, North Korea — not to mention Israel, India, Pakistan …). So objectively speaking, things are probably riskier now than they have ever been, but that risk is spread wider and often less visibly than it was when the US and the USSR were waving ICBMs at each other, with the paradoxical result that most of us no longer give it much thought.

I guess it’s basically that simple.

Gwynne Dyer’s latest Free Press article (April 2, 2012) sheds considerable light. I’ll show it to you sometime, if you wish.