DVD of the Week:

The Moment of Truth (1965) by Francesco Rosi

“The confrontation between intelligence and animal instinct, between reasoning and brute force … without artistry and style, it becomes vulgar butchery, and it’s merely disgusting and cruel.” – Francesco Rosi

Sometimes the subject matter of a film can present an obstacle to judging it fairly as a film. I felt myself faced with this issue when I started watching Criterion’s new release of Francesco Rosi’s The Moment of Truth (1965) because the mere idea of bullfighting appalls me. And yet, as Rosi gets beneath the skin of the subject, I found my reservations disappearing and my appreciation of the film growing.

In the late ’50s and early ’60s, Rosi had made a series of powerful films set in southern Italy, dealing with the influence of organized crime and political corruption on the lives of the people living there, subjects which he would return to again in later years. But after his masterpiece Salvatore Giuliano (1962), he was uncertain what subject to tackle next. What he eventually settled on, with the support of the publisher Angelo Rizzoli as executive producer, was bullfighting in Spain.

The Moment of Truth (1965)

The Moment of Truth differs from Rosi’s earlier work in several ways, most notably in the use of colour for the first time, but also significantly in its setting in a country and culture distanced from the filmmaker’s familiar home ground. On a superficial level, Rosi seems to resort to cliches to deal with the unfamiliarity of the material. The bare bones narrative shares obvious elements with previous melodramas using bullfighting as a backdrop, most notably the various versions of Blood and Sand produced in Hollywood from the 1909 novel by Vicente Blasco Ibáñez.

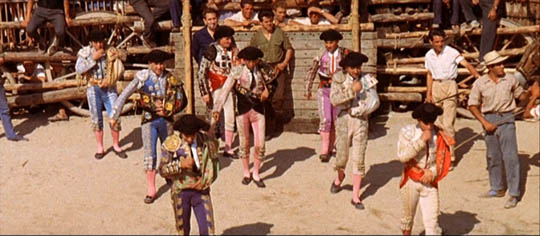

Miguel Romero is the restless son of a farmer struggling to survive in a remote, parched area of Spain. He decides to seek his fortune in Barcelona, but discovers that his tenuous contacts there can’t help him to find work. After months, earning little, unable to get ahead, he sees a poster for a famous matador in a bar and realizes that such a celebrity can make very large sums of money; so he trains as a torero and begins to make a name for himself, until eventually he achieves fame and fortune.

In the four decades since the film was made, it seems to have been largely ignored, or garnered very little critical favour, because of the perceived cliches. And yet, a film is often far more than the sum of its surface elements, and this is the case with The Moment of Truth; the “what” of the story is less important than the “how” of the telling. Rosi had a fine eye for social detail and this film is far richer than a synopsis can convey, while the lush photography perhaps disguises to some degree the director’s neo-realist approach (aside from a brief appearance by actress Linda Christian as a wealthy American woman, the entire cast is non-professional, with many playing versions of themselves). As in his previous works, here Rosi reveals the ways in which social and economic forces constrain and shape an individual’s life.

The film opens with images of a religious festival; a huge, ornate, gold-covered figure of the Virgin is manoeuvred through a narrow doorway into a street crowded with masked figures who look like something out of the Middle Ages. Rosi focuses on the back-breaking labour of the men who have to climb under the effigy and carry it, feet shuffling precariously over stone steps. The parade is joined by armed soldiers and military officers, and with a few brief visual strokes, Rosi has evoked a society (Franco’s Spain) which is crushed under the weight of an alliance between the Church and the military dictatorship.

This is the background against which Miguelin seeks to find a way out of the poverty that weighs his father down.

When he arrives in Barcelona, he has to take a bed in a flop house and eventually gets odd labouring jobs through a money-lender who takes a big cut of his earnings. Becoming a bullfighter seems to be his only option to break the cycle. His casual fearlessness and natural physical grace make him a success … but Rosi’s careful documentary eye shows the bull fights in a way not seen in other, more romantic movies about the subject. Using a 300mm lens, director of photography Gianni di Venanzo, puts the viewer close to the bloody violence; we can see the physical skill of the torero, the risks he takes, but also the madness and pain of the bull as it’s cut and stabbed and bleeding and, with increasing exhaustion, struggles for its life.

These images are disturbing (in fact, di Venanzo eventually left the project because he couldn’t bear to watch any more of the violence, being replaced by Pasquale de Santis). So disturbing, that the excitement of the watching crowds takes on a sick atmosphere, a reminder of the primitive origins of the bullfight, with its echo of Roman “games” in which men fought to the death against other men and against wild animals for the amusement of the crowd, the best gladiators becoming famous, courted by the aristocracy – until their almost inevitable deaths in the arena. That this bloody display seems to offer Miguelin the only way out of poverty in Franco’s Spain becomes an indictment of the military regime and the social and religious forces which kept it in power.

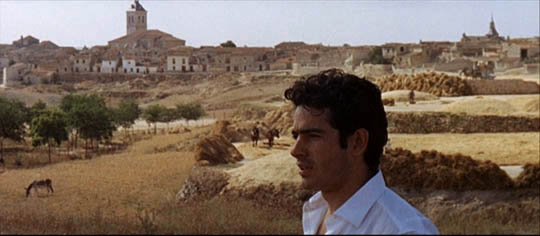

Although Rosi keeps the narrative simple, The Moment of Truth is visually rich and often subtle. When we first encounter Miguel in his village, the place is stark, sun-bleached; when he returns after becoming famous, he sees the place very differently and Rosi’s images reflect that shift in perception – there’s a beauty to the work the villagers do, a nostalgia for simpler rhythms and an immediate connection between life and the work that sustains it.

Early in the film, Miguel returns to his father’s farm from a chaotic scene of running the bulls in the village; he’s immediately put to work going in circles on a small cart which seems to be winnowing grain spread on the open ground. The actual purpose of the task isn’t entirely clear, but the image sums up the kind of life he faces if he stays. Yet when he reaches the city, with no job and virtually no money, he has to take a bed in a bleak dormitory which makes painfully clear just how low he is on the social scale.

In many other bullfighting stories, the dangers of the ring are often paralleled with romantic conflicts – in Blood and Sand, Juan is lured away from his childhood sweetheart Carmen by the bored aristocrat Doña Sol, reflecting the temptations of fame and wealth and providing him with a moral conflict which affects his performance in the ring. In The Moment of Truth, this triangle is reduced and made abstract: when Miguelin returns home to the village a wealthy man, he has a very brief encounter in the fields with a peasant girl, awed by his celebrity, who gives him water to drink in the dry heat. Back in Madrid, at a crowded bourgeois party, he meets the wealthy American woman, who is immediately drawn to the image of power he represents, and they have a single brief sexual encounter in a back room while the party continues nearby. While the traditional narrative conflates the violence in the ring with sexual power, Rosi separates the two; for Miguelin, his career is purely a matter of making money.

In Miguel Mateo, himself a famous bullfighter, Rosi found a natural star, as relaxed in front of the camera as he appears to be in the bull ring. His performance manages to evoke viewer sympathy for the character even as we watch him closely during the moments of bloody slaughter. Unlike so many movies which use bullfighting as a backdrop, this is visceral and ugly, not romanticized, and yet much to my surprise I found it possible to admire the torero’s skill.

Towards the end of the film, once Miguelin has achieved fame and money, he’s forced by his manager to appear in more and more fights, in small towns where there’s no prestige to be gained, and he begins to lose his taste for what he’s doing. The audiences and the men who run the show perceive the spectacle as a mixture of art and entertainment, but for the fighter it has always been nothing more than the means to an end … and inevitably, once his will to continue falters, he’s unable to maintain his performance of the role the system requires of him. As with the life of a gladiator, there’s really only one possible ending.

*

Criterion’s transfer of this little-known film is visually rich, with intense colours. The disk includes a brief interview with Rosi which illuminates the subject and his reasons for tackling it, and Peter Matthews’ essay in the accompanying booklet is informative about the film’s critical reception and its place in the body of Rosi’s work.

Bullfighter and the Lady (Budd Boetticher, 1951)

After watching The Moment of Truth, I dug out a copy of Budd Boetticher’s Bullfighter and the Lady (1951) which a friend had recorded for me some time ago off Turner Classic Movies. I was surprised to find that this black and white movie, shot in Mexico, shared quite a few images and even dramatic moments with Rosi’s film. Although Boetticher necessarily had to stay farther back from the action in the ring, eliminating the visceral shock of the bullfights (he wouldn’t have gotten away with presenting the violence graphically at that time, even if he’d wanted to), the details of the torero’s performance are very similar – an aficionado of bullfighting, Boetticher obviously had an eye for authenticity.

But Bullfighter and the Lady adheres to the more romantic strain of the genre. Johnny Regan (a very blond Robert Stack) is an American hanging out in Mexico with his friends when he’s attracted to Anita de la Vega (Joy Page) in a nightclub where she’s dining with famous matador Manolo Estrada (Gilbert Roland). Seemingly on a whim, Regan asks Estrada to teach him bullfighting. He learns quickly, but his skills are not well matched by his temperament; arrogant and impulsive, he’s more interested in impressing Anita than in dedication to the art. Inevitably, he must be humbled and have the pride knocked out of him before he’s worthy of her love; too bad somebody else has to die for him to learn the lesson.

Boetticher brings to the film the same spare narrative skills which made his westerns so good, but he seems blind to the fact that his protagonist is thoroughly unsympathetic, that the story of his growth and redemption doesn’t engage the viewer because, frankly, the guy’s a jerk. The poise and dignity of the Mexican characters merely make him look even more boorish and irritating. I’m not sure how I would have reacted to this movie if I hadn’t just seen The Moment of Truth, but despite the annoying central character, in light of what I’d just learned from Rosi, it impressed me with the air of authenticity Boetticher brought to the scenes in the bull ring.

Comments