Film(ed) poetry: The Song of Lunch (2010)

Some things just sound like a bad idea. In 2010, Greg Wise, an executive producer at the BBC, decided to commission an adaptation of a long narrative poem by Christopher Reid to mark National Poetry Day in Britain. That poem, The Song of Lunch, tells of a bitter, sarcastic failed writer and editor who arranges to have lunch with an old lover, whom he hasn’t seen in 15 years … not since she left him to marry a famous and successful author. She now lives in Paris with her husband and two children, but pops over to London for a reunion in a small Italian restaurant in Soho where they used to spend time during their affair.

It all sounds rather contrived and literary.

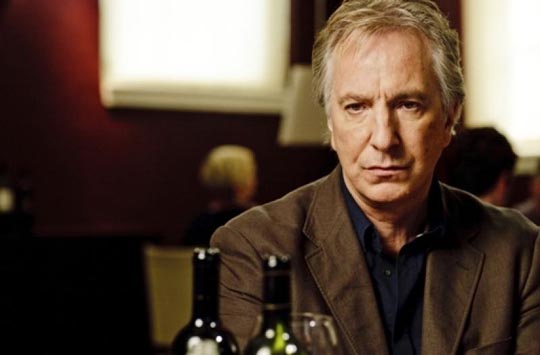

The surprise is that The Song of Lunch, as adapted and directed by Niall MacCormick, is both witty and surprisingly rich in emotion. For a film based on a poem, in which intoxication plays a major part – love, lust, wine – it’s perhaps logical that it’s steeped in words. And at first, it seems that the words, a running monologue narrating and dissecting the story, will overwhelm the drama. In the opening minutes, the images illustrate exactly what is being said in a completely literal way. But as the story unfolds between “he” (Alan Rickman) and “she” (Emma Thompson), the words and images begin to resonate with one another.

What we hear in the voice-over becomes a sardonic, bitter, defensive strategy on “his” part, which crumbles and collapses as the lunch fails to go the way he had hoped. It’s not entirely clear what he had expected would come of the meeting, perhaps simply that the intervening fifteen years would disappear and he would once again find himself in the state of happiness he imagines existed during their affair.

However, the combination of his jealousy and the bitterness he feels about his own literary failure (one unsuccessful book of poetry) makes things go wrong from the start. When “she” arrives, she’s warm and friendly, obviously having come with fond memories of an old affection. But his prickly responses quickly push her away. He can’t conceal his anger and disappointment, even though he realizes that those feelings are at war with his own erotic attraction to her.

There’s very little actual dialogue in the film, but what there is is skillfully woven into the voice-over, as counterpoint and disruption, gradually tearing his defences to shreds. The more apparent it becomes that she is no longer available to him, the more desperate he grows … and the more he drinks, retreating into himself. As she tells him at one point, he’s there physically, but is emotionally and psychologically disappearing … “even at your own lunch, you’re out to lunch.”

As rich as the words are, and as finely polished as the images are, the real strength of The Song of Lunch is the cast. Emma Thompson has probably never been more radiant than she is here, seen through the desperate eyes of a former lover, while Alan Rickman offers a finely tuned portrait in middle-aged desperation, a sense of failure oozing from slack grey skin, eyes barely able to remain open as he sinks deeper inside himself. The aura of self-loathing he gives off tells us everything we need to know about the crucial choice “she” made 15 years ago.

Although it takes a little while to adjust to the film’s style and pace, with small moments drawn out at length to provide sufficient room for all the words, The Song of Lunch is funny, moving, even erotic. This 50-minute adaptation of a poem, written, directed and performed with adults in mind, is one of the finest pieces of entertainment to appear in some time.

The BBC/2entertain DVD presents this excellent short film in a beautifully clear anamorphic transfer. There are no extras on the disk, which is a pity as a commentary from writer-director MacCormick could have offered some interesting insights into the process of transforming poetry into visual storytelling.

Comments

Where can I buy the song of lunch please?

I’m afraid it seems to be out-of-print, but there are used copies available on eBay.