Stanley Kubrick 5A: Science Fiction – 2001: A Space Odyssey

I first saw Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey in St. John’s, Newfoundland, when I was 13. Like a lot of people back then, I responded to it as an “experience” rather than a narrative. I don’t think I even thought about what it might “mean”, I just got caught up in the imagery, the hypnotic pace, the sense of being given access to an imaginary world.

The last time I saw it in a theatre was January 12, 1992. I remember that so precisely because it was HAL’s birthday. I got a strange chill when the computer gave the date as mission commander Dave Bowman methodically dismantled his memory banks. It was a Sunday afternoon screening at the Cinematheque here in Winnipeg, and the print was in terrible shape, scratched and battered, with the colour shifted towards red. Programmer Dave Barber hadn’t realized that he was showing it on HAL’s birthday … just an odd instance of synchronicity.

I’ve seen the film quite a few times on video, first on VHS and later in various DVD editions, each re-visit taking on a kind of ritual aspect, but it’s always been a little disappointing because, even on DVD, the format didn’t seem to be able to handle the level of visual detail in the imagery. That problem has been rectified in Warner Brothers’ beautiful Blu-ray edition.

2001: A Space Odyssey (1968)

Kubrick’s science fiction masterpiece marks a watershed in the genre. It went so far beyond what had come before in terms of content and technique that it became the standard by which everything else would have to be judged, and it challenged every filmmaker who came after to aim for greater visual realism and narrative complexity. Unambitious projects still got made (Michael Anderson’s silly Logan’s Run [1976], Jack Smight’s travesty Damnation Alley [1977]), but they were immediately recognized as shoddy, second-rate work. Even though Star Wars (1977) ditched Kubrick’s rigorous attention to realism, Lucas and his team nonetheless put a great deal of effort into the details of the pulpy world they were creating. Ridley Scott was closer to Kubrick in Alien (1979) and Blade Runner (1982), although those films lacked Kubrick’s thematic ambitions.

The narrative of 2001 is actually quite slender, though it spans millions of years. Beginning at the “dawn of man”, as the opening title puts it, it traces human evolution from its animal beginnings to the 21st Century and on to the next stage. This progression is initiated by an unknown alien force which manifests at three different stages as a featureless black monolith which mysteriously pushes mankind forward. We have no idea what motivates these aliens, but what is clear is that progress is inextricably linked to aggression and violence. Here Kubrick and co-writer Arthur C. Clarke are proposing an external explanation for the self-destructive tendencies which are so often the subject of Kubrick’s films. (This underlying concept bears a strong resemblance to Nigel Kneale’s Quatermass and the Pit, first aired as a BBC serial in 1958, then adapted by Hammer Films as a feature in 1967.)

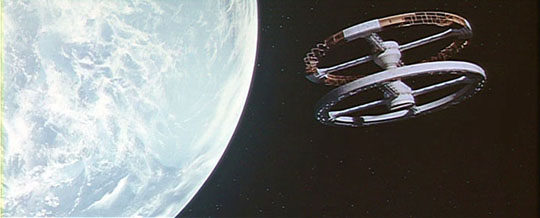

In the most famous jump-cut in movie history, Kubrick leaps several million years from the paleolithic discovery of weapons to the technological near-future where the planet is circled by weapons-bearing satellites and the world’s population lives in the shadow of the Cold War with its permanent threat of annihilation. Human progress has been accompanied by, really driven by paranoia, inventiveness fuelled by fear and suspicion.

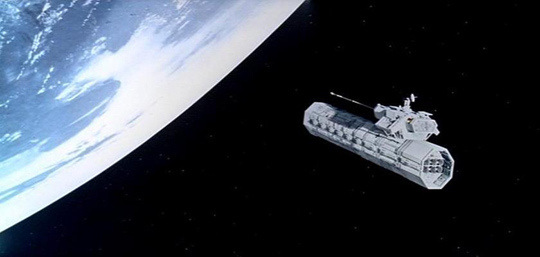

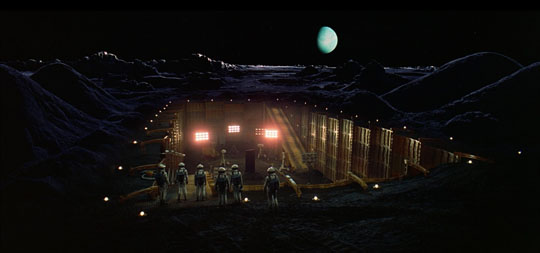

The Americans have discovered an artifact on the moon, another of the black monoliths, buried in the crater Tycho for millions of years. When struck by sunlight, the now-exposed object emits a signal aimed at Jupiter. While the authorities keep its existence secret, an expedition is sent to Jupiter. Three members of the crew are in suspended animation, while the other two, Dave Bowman (Keir Dullea) and Frank Poole (Gary Lockwood), have not been told the purpose of the mission. Only the on-board computer, HAL 9000 (voiced by Douglas Rain), has that information.

In a typical Kubrick move, the computer is the most human character in the film, the two astronauts being incurious technocrats who carry out their duties with machine-like detachment. But in giving HAL a human-like personality, the computer’s creators have inadvertently also given him human weaknesses. As the mission progresses, HAL exhibits increasingly neurotic tendencies. He is in fact infected with the distrust and paranoia which defines the human species in the film. Convinced that only he can be trusted, that his human companions are a threat to the mission, he sets out to kill them all.

His cold-blooded acts of murder are met with an equally cold-blooded retribution as Bowman methodically disconnects HAL’s memory circuits, erasing consciousness and personality.

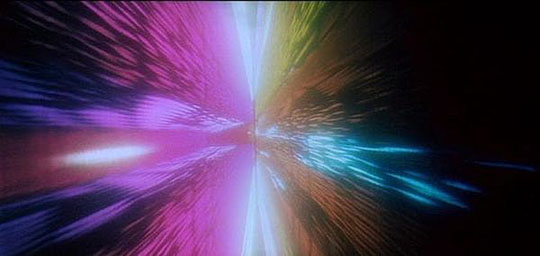

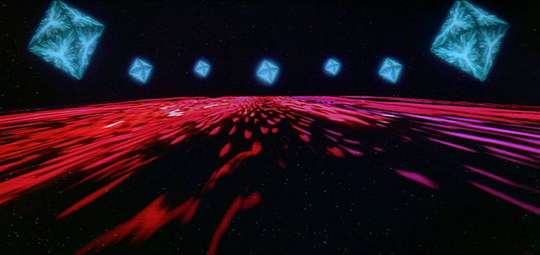

In the final section of the film, the “trip” which appealed to counter-culture viewers back in the late ’60s, Bowman passes through some kind of cosmic gateway to a place where the still-unseen aliens transform him to the next stage of evolution. Even here, we never know what the plan is, what exactly constitutes that next stage. We’re left with a final image of the Star Child hovering above Earth with a disinterested gaze.

What does it all mean? Kubrick and Clarke offer no explanations. What they have created is a powerful image of the awesome scale of the cosmos and the smallness of humanity within it. And yet they also suggest that there is a purpose to existence; we’re just not equipped to understand it … yet.

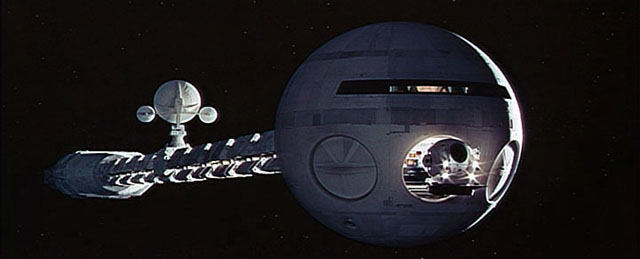

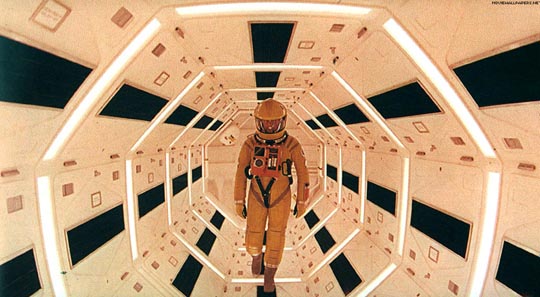

Whatever the philosophical implications of 2001: A Space Odyssey, on a material level it remains unsurpassed as an evocation of space travel. The richness of the design, the complexity of the use of sound, the combination of the mundane (commuter spaceflight, Dr. Heywood Floyd chatting to his young daughter on a video phone, eating processed meals in flight) and the majestic (the delicate shape of the Discovery floating silently against a background of stars, the elaborate light show of the Star Gate) give the film a sense of realism which still sets the standard for science fiction cinema. And of course, what’s even more remarkable is that this was all accomplished by purely optical means, with models and photographic techniques, with Douglas Trumbull, Con Pederson and the rest of the team pushing the limits of what was possible long before computers were capable of producing today’s ubiquitous synthetic effects.

Comments

Now that you mention it, I think my own viewings of 2001 in the past have been somewhat ritualistic, not overly concerned with narrative. The film used to come to Winnipeg in one-week runs back in the 1970s, usually to the Grant Park Cinema, which had the city’s only Cinerama screen, I think. I used to go a couple of times each week it was here, alone, just soaking in the imagery of the film. I also read Clarke’s novelization a number of times. For years, I’d watch the film and feel that something had been cut out, only to remember that it had been a scene in the book.

Anyway, good post. I’ll have to pick up the Blue Ray. I have the DVD, and it looks really good. At 720p it’s much better than watching the DVD on an older TV.

And completely unrelated. Another great jump cut: Dark Night of the Scarecrow. Farmer falls into wood chipper, cut to raspberry jelly being slopped onto a plate in a diner. Always liked that one.

Yes, that woodchipper/jelly cut has stuck with me since I first saw Dark Night of the Scarecrow back in 1981 …

I remember where, when (summer of ’68…the original Wpg. showing?) and whom I was with when I first saw it. I told my parents they must see it … they would love it.

They were bored to death. I think my father actually dozed off.

I never recommended a movie for them again.