Stanley Kubrick 5B: Science Fiction – A Clockwork Orange

Anthony Burgess wrote his short novel A Clockwork Orange in 1962 as a way of coming to terms with the rape of his first wife. It may seem odd then that the book takes the first person point of view of Alex, a 14-year-old boy, who commits numerous crimes, including rape and murder. In addition, Burgess wrote the story in a dense mixture of English and Russian, a vivid slang he called “nadsat”, which further implicates the reader in the protagonist’s worldview. The theme of the novel is the innate tendency towards violence in human nature and the problem of free will … to what degree does the individual have control over his own behaviour and the potential to choose good over evil?

Stanley Kubrick was introduced to the book by Terry Southern while they were collaborating on Dr. Strangelove, but it held little appeal for him because he found the language alienating and couldn’t see a way of translating it to the screen. But, strangely, after the release of 2001: A Space Odyssey (which was not greeted entirely enthusiastically by MGM until it became clear that it had such a strong appeal to the counter-culture), Kubrick felt the need to prove that he could make a commercially successful low budget feature. And he turned to Burgess’s novel for the basis of that project. This, of course, was the second time – after Lolita – that Kubrick had been drawn to adapt an “unfilmable” book.

Unsatisfied with Burgess’s own attempt at a script, Kubrick ended up writing the screenplay himself, resulting in the most problematic and controversial film of his career, a status which it retains to this day.

I first saw A Clockwork Orange in the spring of 1972 at the Warner West End in Leicester Square, a huge theatre. The film was strange, both funny and disturbing, its visual surfaces seemingly polished to perfection, while its stylized technique and implausible narrative structure were the antithesis of the kind of realism the director had brought to Dr. Strangelove and 2001.

For some reason, I’ve kept returning to the film over the years and have probably seen it more times than any other Kubrick movie, and my responses to it have shifted numerous times. For a while, it came to seem dated and cartoonish, a conceptual mistake, but watching it again on Warner’s new Blu-ray, its bold visuals and aggressive narrative technique mark it as one of the director’s strongest films, though it remains no less troubling than it was back in 1972.

A Clockwork Orange (1971)

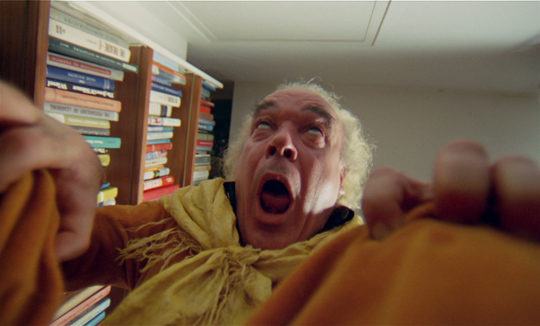

Kubrick’s adaptation has an allegorical structure in which the second half is a mirror image of the first, creating a kind of formal argument about the issue of violence and free will. The first act introduces us to Alex and his three droogs, Georgie, Pete and Dim, as they tune themselves up with drugs at a milk bar prior to a night of fun activities. First up, they savagely beat an old drunk in an underpass; then they attack a rival gang, whom they interrupt as they prepare to rape a young woman; then they steal a car and terrorize nighttime travellers before committing a home invasion during which they beat a writer and rape the man’s wife.

In the second half of the film, after Alex’s conditioning and release from prison, he again meets the old drunk and is beaten by him and his cronies; this is interrupted by two police officers who turn out to be Georgie and Dim, now of working age. His old gang members take him to a remote place in the country and beat him half to death. Dragging himself through a storm at night, he ends up back at the house of the writer, where he is taken in and helped as a victim of the fascist state … but when he gives himself away, the now-crippled writer and his friends conspire to drive Alex to his death in order to embarrass the government which destroyed his will with their experimental conditioning.

In the first half of the film, Alex acts freely and expresses himself solely through vicious anti-social behaviour; in the second half, after the conditioning which has stripped him of his ability to act freely, he becomes a victim of everyone he meets, subject to the kind of treatment he used to mete out to others for “fun”.

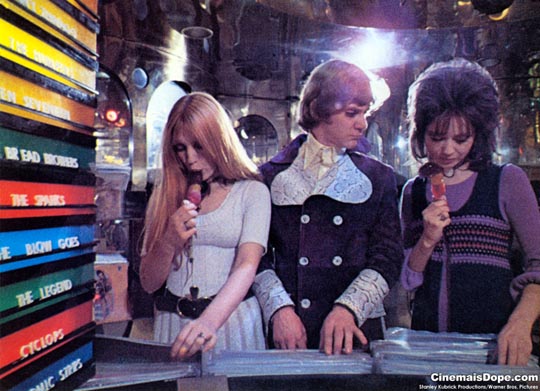

Here we see clearly the view of human nature laid out by Kubrick and Clarke in 2001: A Space Odyssey. The driving force of human evolution has been violent competition, but the process has become exhausted by the time we reach the future of A Clockwork Orange. It’s tempting to see the two films as sharing the same world, the events of A Clockwork Orange unfolding on the planet below the space station and armed satellites and moon colonies from which the Jupiter mission is launched – that this evolutionary exhaustion is one of the reasons for the aliens to push us towards the next stage of human development. There’s certainly a shared sense of design between the two films, a kind of sterile modernism – the stark functionality of the space station decor in 2001, all the shallow “art” on display in A Clockwork Orange, crass, pornographic, aesthetically bankrupt. Alex’s love of Beethoven is the only sign of culture in sight, but even this music transports him to fantasies of violence and perversion.

Violence pervades the world of A Clockwork Orange – the droogs, the police, the prison authorities, the medical establishment, the government, the government’s opponents, everyone is inflicting some form of violence or other on someone else. But Kubrick doesn’t present it realistically – that would have been a very different film. Here, the violence committed by Alex and his gang is presented as performance. This is the closest Kubrick ever came to making a musical. The old drunk is happily singing Sweet Molly Malone to himself when Alex and the droogs descend on him; the rival gang are set to rape their victim on the ornate stage of a derelict old theatre, and the fight is choreographed to Rossini’s Thieving Magpie; and of course, most notoriously, the attack on the writer and his wife is performed to Singin’ In the Rain. These all come across as expressions of, for want of a better word, joy in Alex’s freedom.

When the tables are turned and he becomes the victim, the beatings are accompanied by the discordant, atonal synthesizer of Wendy Carlos, that earlier joy replaced by a brooding, almost sinister, contemplation of the savagery being visited on the helpless Alex.

Burgess’s original novel ended with a chapter in which Alex matures; becoming an adult, he rejects his childish nihilism and loses his urge to inflict pain on others. That chapter was dropped from the book by the American publisher, and Kubrick wasn’t aware of it when he wrote the script. He based his adaptation on the truncated American edition, a decision which displeased Burgess. The ending as it now stands is ambiguous. After surviving his suicide attempt, Alex is de-conditioned, restoring his will, and the Minister of the Interior heaps rewards on him – a new life, money, a job … and listening to the final movement of Beethoven’s 9th, Alex sinks into a state of ecstasy, a fantasy of sex in front of a cheering crowd, and his final words on the soundtrack are “I was cured all right.”

But what exactly does that mean? He has once again lost all inhibition, but now he’s no longer an outlaw; his urges have received official sanction, and he’s been incorporated into the repressive political culture which had tried to destroy him. The subtext of this seemingly joyful ending is thoroughly chilling.

Reaction

Although A Clockwork Orange was released on the heels of Ken Russell’s The Devils and Sam Peckinpah’s Straw Dogs, both of which suffered to some degree in the hands of the censors, Kubrick’s film was passed uncut by the British Board of Film Censors. Surprisingly, the Board saw the violence, the sex, and the sexualized violence as integral to the filmmaker’s artistic intentions. This no doubt had something to do with the stylization, quite unlike the graphic realism of the other two films. Still, on release, A Clockwork Orange triggered some strong critical reaction from the conservative press.

But more interesting than the somewhat predictable critical reaction was the social reaction. Suddenly, Kubrick’s film was being blamed for any and every kind of anti-social behaviour. Criminals caught in the act were quick to grasp this opportunity and a common defence in the courts became “I saw A Clockwork Orange and it made me do it.” A fascinating commentary on the film’s themes of free will and conditioning, but in a way the film invited such a response. Kubrick was so successful in anchoring his movie to Alex’s point of view that at no time is there any expression of empathy for his victims; and after his conditioning, there’s only room for his own self-pity … his former victims, when they turn on him, are shown as grotesque monsters. Perhaps too successful in his satirical intent, Kubrick had made a film which seemed to valorize the young thug at its centre.

Anthony Burgess, who had been ambivalent about the adaptation, eventually got tired, as he said, of the press calling him up every time a nun was raped to ask him about the influence of the book and film on the crime. In time, he actually repudiated his own novel, regretting that he’d written it because it was so widely misunderstood.

The consequences of the film were quite serious for Kubrick himself; he and his family began to receive death threats because of it and, as a point of personal safety, he persuaded Warners to allow him to suppress A Clockwork Orange in Britain two years after its release, and it remained unseen there until after his death. Although there were some reports that he withdrew the film because of supposed copycat crimes, it was actually more a question of his family’s safety … which makes more sense than the copycat theory, because if he had actually believed that the film was inspiring acts of violence, it would have been pretty hypocritical to suppress it in Britain while it continued to be seen everywhere else in the world.

Comments

Like you, I’ve seen A CLOCKWORK ORANGE more times than any other Kubrick film. Like you, my reactions to it have changed over time. At one point, I couldn’t understand the furor over the violence… it was clearly so stylized as to lack the impact of more realistic gore. When I saw it again this year, on the other hand, the violence struck me as more savage and powerful than many of the films I’ve seen since the 1970s that were far more violent… the “Singing in the Rain” rape scene in particular. It’s still one of my favourite Kubrick films.

As a short post script, my first introduction to the film was actually the Mad Magazine parody in 1973: A CROCKWORK LEMON.

I read a lot of those Mad Magazine parodies myself, though damned if I can remember any of them except Voyage to See What’s on the Bottom, which of course was a masterpiece.