The Passion of Mel Gibson

I used to like Mel Gibson, particularly in his early, Australian period. I’m still a big fan of the Mad Max trilogy (1979-85), and although they may not seem quite as impressive now as when they were first released, Peter Weir’s Gallipoli (1981) and The Year of Living Dangerously (1982) are both still worth watching. After Gibson went to Hollywood he specialized in action comedies (the Lethal Weapon series [1987-98], Bird On A Wire [1990]), thrillers (Ransom [1996], Conspiracy Theory [1997]), and an odd assortment of more serious films (Mrs Soffel [1984], Hamlet [1990]).

And then he started to direct and it gradually became apparent that he had some grandiose ideas and a masochistic streak – the deformed character he played in The Man Without a Face (1993), the Scottish martyr William Wallace in Braveheart (1995). But in retrospect that tendency towards masochism and martyrdom was there at the start. Max Rockatansky is subjected to some pretty harsh treatment, and Frank Dunne in Gallipoli is sacrificed to the hubris of the British commanders who squandered colonial lives in pointless WW1 battles.

Which brings us finally to The Passion of the Christ (2004). Despite the masses of publicity when it was released, I had little interest in going to see it. It sounded like one of the strangest vanity projects ever made, with Gibson investing his own money to show in detail the physical torments suffered by Jesus in his last days. Not that I haven’t seen my share of gruesome and nasty movies, but the air of religious fervour surrounding the project put me off. Confession: I was raised in a completely agnostic family and as a result the powerful hold that tribal squabbles in a small area of the Middle East thousands of years ago have had and continue to have on western civilization is a complete puzzle to me. Not to mention the two thousand years of savagery and oppression committed in Christ’s name which followed those events. But having recently come across a Blu-ray copy of The Passion for five bucks, I decided that its cultural impact justified taking a look.

The Passion of the Christ (2004)

Hollywood has been drawn repeatedly to the Bible since the very earliest days of the movies. The Book’s mixture of sex and violence leavened with moral lessons has suited the commercial demands of the industry, offering apparent justification for titillation which gets past the censors thanks to the accompanying finger-wagging condemnation. Exploitation disguised as uplift. Cecil B. DeMille returned to the source repeatedly, with the silent King of Kings (1927), a fairly straight-forward account of the life of Christ; The Ten Commandments (1923), which begins with Moses and the exodus from Egypt, then jumps ahead to a contemporary story in which the impact of the commandments plays out in the lives of two brothers; and then once more in his final movie in 1956, The Ten Commandments again, but this time sticking to the story of Moses in one of the greatest kitsch epics ever to come out of Hollywood. Stories like Ben-Hur (1925, 1959), The Robe (1953), The Sign of the Cross (1932, DeMille again) treated the source tangentially, often with a ponderous piety, depicting the impact of Jesus on various real and fictional historical characters. And of course the life of Jesus himself has been a perennial favourite: George Stevens’ The Greatest Story Ever Told (1965); Nicholas Ray’s King of Kings (1961); Scorsese’s The Last Temptation of Christ (1988); and far outside Hollywood, Pasolini’s The Gospel According to St. Matthew (1964), which perhaps stands alone as a realist treatment of the story …

Scorsese’s movie offers an interesting comparison with Gibson’s, particularly with regard to its reception. There were widespread, vocal protests against Scorsese’s “sacrilegious” treatment of the story, particularly in the final part of the film in which, while on the cross, Jesus has a vision of what life might have been if he had not followed his sacrificial role to its final conclusion. There was outrage at the idea that Jesus could be considered as a man rather than a purely spiritual being devoid of normal human desires … no matter that in the end he rejects that human part of himself and embraces the role assigned to him as the Messiah.

In contrast, Gibson’s film was widely embraced by the religious right in the States, with entire congregations busing in to share the experience. But what was that experience?

Most mainstream movies about Jesus have focused on the life and teachings, the moral lessons he offered to inspire people to live decent lives, always inevitably culminating in the final sacrifice. In narrative terms, surely the purpose of that sacrifice was to fix in memory everything that came before, to give some lasting life to the lessons and philosophy. And of course, Jesus had some very fine things to say; if those who professed to follow him in the ensuing two millennia had actually subscribed to his precepts the world would no doubt be a better place than it is … But despite the content of the teachings, historically there’s been a strong connection between what has been made of Jesus by the institutions built in his name and patterns of social horror – the Crusades, the Inquisition, genocide in the New World, the persecution of “witches” and non-believers …

The structure of the story of Christ is actually one familiar from many cultures, thoroughly documented by James George Frazer in The Golden Bough (1890), his massive comparative study of religious myths from around the world. In culture after culture, Frazer came across the story of the god-king ritually sacrificed in order to renew the world, a practice rooted in the cyclical nature of the seasons – birth, life, death, rebirth – and usually tied to the vernal equinox, the time when life begins to return. Not surprisingly, Easter occurs close to that time every year.

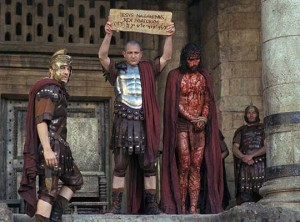

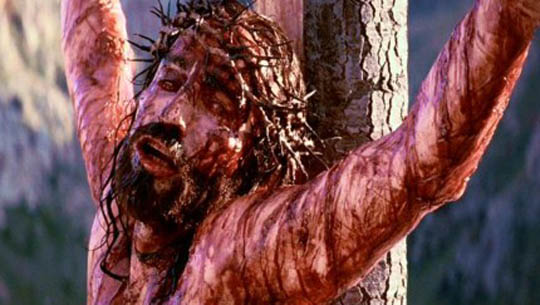

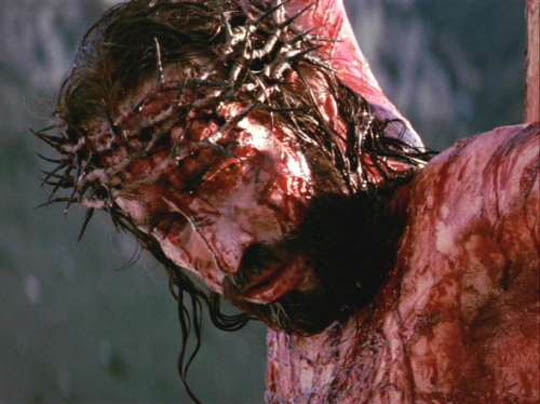

Gibson in The Passion ditches the entire life of Jesus in order to concentrate unremittingly on his death. The film covers the final hours from the arrest in Gethsemane (visually the most interesting part of the film; as shot by the great Caleb Deschanel it resembles something out of a silent movie, the garden like an elaborate studio set, all tinted blue to denote night), through the trial, the appearances before Pilate and Herod, the scourging, the long walk to Calvary and finally the lingering death on the cross. This grueling spectacle is interrupted only briefly by a handful of quick flashbacks in which we get a few soundbites to remind us of who the suffering victim is.

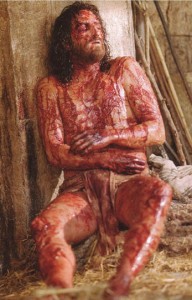

Having reduced Jesus to a purely physical being by this focus on the brutality inflicted on him, Gibson proceeds to destroy that physical body with a ferocity unprecedented outside of horror movies. The closest comparison is perhaps the brutal punishment of Urbain Grandier in Ken Russell’s The Devils (1971); as in The Passion, this suffering is inflicted by religious authorities for supposedly pious reasons, though in truth in both cases the reasons are political and rooted in an effort to maintain power which is threatened by a single figure who has raised questions about that power’s legitimacy. The difference between the two films is that in Russell’s masterpiece the worldly Grandier gradually assumes spiritual authority through his suffering, while Gibson is unable to transcend the grossly physical limits of the tortured body.

This is the story of Christ for an age in which torture has become an ingrained element of entertainment. Gibson offers a relentless lesson in the horror of the flesh and the unremitting nastiness of human beings, a movie concocted by the modern equivalent of the flagellants of the Middle Ages who found physical existence so vile that they wanted only to strip away their own bodies and purge all the feelings, needs and desires that existed within them …

Traditionally, martyrdom is rooted in a sacrifice which sets an example for others; with Gibson, it’s more about stirring anger and thoughts of revenge. Concentrating purely on the grim physical violence of Christ’s death, this treatment clearly suits the present climate of religious extremism. Gibson gives us a story of Christ designed not to evoke piety in the audience but rather to fire up hatred and a desire to smite, rather than love, one’s enemies … in effect, Christ as Mad Max. All of which fits very snugly with the grim anger of the current religious right.

For Gibson, the “meaning” of Christ isn’t in the moral lessons he taught, lessons which threatened the status quo and brought down the wrath of the authorities who held sway at the time; Christ’s meaning resides solely in the physical punishment inflicted on his body. Gibson’s religion is suffused with a Manichaean fury. The film is a graphically detailed depiction of the flesh being stripped away, supposedly to free the spirit. But all thoughts of spirit get lost in the spectacle and as the blows continue to fall relentlessly on the mutilated body, the viewer is beaten into weary submission and forced to see that our physical existence is unutterably vile and the flesh needs to be obliterated.

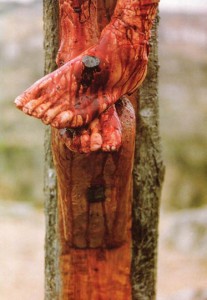

The film’s final image, inside the sepulchre as Jesus rises again, focuses on a closeup of his punctured hand; then he strides out of frame, heading back into the world like an avenging hero embarking on his mission. Gone are the kitschy pieties of Hollywood and all that remains is a sequel-ready righteous blood-lust. Revenge of the Christ?

Comments

Religulous.