DVD of the Week: A Night to Remember (1958)

To mark the centenary of the sinking of the Titanic, just as James Cameron releases a 3D version of his 1997 moneymaking behemoth, Criterion has brought out a new edition of Roy Ward Baker’s A Night to Remember (1958), still the best version of the story. The two-disk DVD (also available on Blu-ray) offers a beautiful new hi-def transfer of the film, shot by the great Geoffrey Unsworth, and includes all the extras from the original 1998 edition (one of the first DVDs the company ever released), plus several new supplements.

After 100 years, the story of the Titanic still maintains a powerful hold on the popular imagination. There have been other maritime disasters which cost more lives, but the sinking of the Titanic on the night of April 14-15, 1912, is the one we remember. There are a number of reasons for this, perhaps the chief one being that the fate of the ship has the elements of classical tragedy – it wasn’t simply the sinking of a ship; it was a narrative imbued with great themes.

At the time of the Titanic‘s maiden voyage, the ship represented the pinnacle of human technological development. It was the biggest, fastest, most complex feat of engineering yet accomplished. As a character early in A Night to Remember puts it: the Titanic was “man’s final victory over nature and the elements.” Our inventiveness had finally superseded the powers of the natural world, and surely nothing could stop us as we embarked on a new century rising from the rich soil of the just ended Victorian Age. Although the builders never made the claim, the public believed that this modern marvel was literally unsinkable. In other words, the Titanic was the very embodiment of hubris and, as in all classical Greek drama, its mere existence called for some retribution from the gods to humble our arrogance and put us back in our place. The Titanic didn’t simply hit an iceberg; it hit a massive symbol, one which was easily grasped by even the most unsophisticated mind.

But there was more to the story than technological arrogance; there was a complex social narrative involving every stratum of contemporary society, from the richest of the rich to the poorest of the poor, all overseen by the technocrats and businessmen who had built the mighty ship. No wonder the story has been returned to again and again; it offers numerous narrative possibilities.

The Titanic on film

The first feature dealing with the event (in a highly fictionalized way) was apparently E. A. Dupont’s Titanic (aka Atlantik), made in both German and English versions in 1929 (a clip can be seen on the BFI’s YouTube channel, here). In 1943, the Nazi film industry produced Titanic, directed by Herbert Selpin, in which the limitless greed of British and American capitalists brings about the disaster, with only the fictional German 1st Officer Petersen foreseeing the coming catastrophe, his warnings going unheeded as the owners force the ship on at full speed in order to push up stock prices and their own profits. In 1953, Hollywood produced Titanic, directed by Jean Negulesco, in which a wealthy couple whose marriage is failing find themselves caught in the disaster. The wife can no longer stand her husband’s social pretensions and wants to return to America where her children can be raised in a decent, stable middle-class environment, but once the ship begins to sink, their differences lose all import and the effete husband discovers his own inner nobility.

In 1997, of course, James Cameron came out with his bloated, CG-enhanced epic which somehow managed to reduce the disaster to background for a teen romance, merely there to provide Jack and Rose with some unearned gravitas.

A Night to Remember (1958)

The most authentic version of the story remains Baker’s A Night to Remember, adapted by novelist Eric Ambler from Walter Lord’s account of the tragedy which drew extensively on the records of the official enquiries as well as the memories of many of the survivors who were still alive in the early ’50s. Writer Ambler, director Baker and producer William MacQuitty had all worked together on documentaries during the war, and the influence of that work is apparent in the scrupulous attention to detail and the sense of realism which marks the project. One of the most ambitious British films of the decade, A Night to Remember avoids the pull of melodrama and focuses on the ship and the event rather than any particular passenger’s personal story. This gives it a sober, documentary-like tone, aided by a large cast of excellent actors, none of whom were “stars”, as well as impressive production design and effects work involving large-scale miniatures in addition to full-size exterior sets of sections of the ship which could be submerged. Shot on cold nights, you can virtually feel the physical horror of going down in the icy North Atlantic.

One of the most important elements of the story is, of course, the fact that the Titanic didn’t carry enough lifeboats for everyone on board. Board of Trade regulations at the time required that any ship over 10,000 tons must carry 16 lifeboats with a capacity of 990 occupants, so although the Titanic was built with the capability of carrying up to 64 lifeboats, by having 20 boats with a total capacity of almost 1200 the White Star management actually exceeded regulatory requirements. The fact that this was completely inadequate for the more than 2200 people on board indicates that the idea of any possible sinking simply didn’t enter the company’s collective mind. As survivor Eva Hart says in one of the disk’s supplements, if there had been sufficient lifeboats aboard, the two hours and forty minutes it took for the ship to sink would have been more than enough time to save everyone, and the whole incident would just be a maritime footnote today. The real cause of the loss of life was not the iceberg, but rather arrogance and a failure to comprehend the true nature of this technological marvel.

Implicit in A Night to Remember is the idea that this ship, symbolic of the great new century, was carrying an entire social order which was about to end. The extremes of inequality, the unquestioned rules which kept the poor steerage passengers penned up below decks while the wealthy had time to get into the inadequate lifeboats, the overwrought sense of chivalry which pushed the notion of “women and children first” to a point at which it seemed almost required that the men stay aboard and accept a noble death (despite a capacity of almost 1200, the boats ended up saving only 700, some of them launched with only a handful of occupants) … all the rules which supposedly underlay the Victorian and Edwardian world view clashed with the forces of a technology whose power was beyond comprehension. In effect, just two years before the eruption of the First World War, the Titanic offered, in microcosm, a taste of what was about to come.

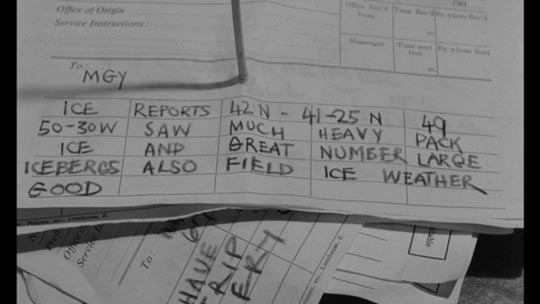

Again and again in the film we see individual errors, human failings, which contribute to the devastating impact; radio was still in its infancy and was poorly used, both on the Titanic itself and on other ships that night which ignored or misinterpreted the desperate calls for help; emergency signal rockets were seen by a ship not far off, but ignored because those on watch weren’t sure what they meant … the implication is that as we advance our technologies we are always a step or two behind our own inventions.

All of this is captured by Baker’s film without ever needing to be stated openly, evoking the underlying appeal which has kept the story alive for a century but without clouding it with the trivializing melodrama which other versions have fallen into. We get moving glimpses of the emotional impact of families torn apart, of people fatalistically accepting their own impending deaths, but these moments stand as representative of the larger experience rather than as mini dramas in their own right. Ambler and Baker know that the event itself is terrible enough without needing to oversell the human details, and their restraint adds to the power of each incident.

The Criterion supplements

The supplements carried over from the earlier edition include an audio commentary by Titanic experts Don Lynch and Ken Marschall, who appreciate the film’s achievement and yet quite frequently nit-pick about what they see as technical shortcomings. However, they do offer some illuminating comments about various characters and incidents. There is also Ray Johnson’s 1993 documentary, The Making of A Night to Remember, which has extensive interview clips with Walter Lord and producer William MacQuitty, who as a 6-year-old in Belfast actually saw the ship launched. The documentary also features a lot of behind the scenes footage, showing the scale of the production and the harsh conditions the actors had to endure on the shoot.

The new material includes an engaging 23-minute interview with survivor Eva Hart, whose memories of the event, although she was just a child at the time of the sinking, are still vivid; a half-hour production from Swedish television made for the 50th anniversary of the sinking, which combines excerpts from Baker’s film and interviews with a Swedish survivor and her two daughters, both of whom were too young to really remember anything of the event; and a portentous BBC documentary called The Iceberg That Sank the Titanic, which mixes some interesting information about the science of icebergs with overwrought speculation about the particular berg struck by the ship.

Altogether, this new edition is a worthwhile upgrade of a film which will continue to fascinate long after this year’s 100th anniversary has passed.

Comments

One thought on “DVD of the Week: A Night to Remember (1958)”