DVD of the Week: The War Room (1993)

D. A. Pennebaker was one of the founders of direct cinema, working with people like Richard Leacock and the Maysles brothers, Albert and David, to free documentary from the limitations of the voice-of-god narrator and didactic purpose. Their idea was that documentary should merely observe and record events, with no narration to impose interpretation. But of course, like all filmmaking, direct cinema, or cinema verite, is a constructed form, its methods a powerful way of persuading viewers that they’re watching unmediated reality. At its best, the form provides a convincing you-are-there feel.

In the past couple of decades, however, it’s a form that has become outmoded (or corrupted) by digital media, the Internet, 24-hour cable news … the endless inundation of “information” we’re now faced with. Genuine direct cinema is a form which requires real observational skills and the time necessary for introspection, to shape the material in ways that undigested “breaking news” and crassly scripted “reality TV” are incapable of. By its very nature, this kind of film, when focused on current events, will now already seem like old news by the time it gets released. So direct cinema has largely been replaced by a ramped up version of the old authoritarian documentary, at its best practiced by filmmakers like Charles Ferguson (No End in Sight [2007]), Alex Gibney (Taxi to the Dark Side [2007]) and Eugene Jarecki (Why We Fight [2005]); more questionable is the new “documentarian as celebrity” genre, with people like Michael Moore and Morgan Spurlock inserting themselves into the material as personalized voices-of-god.

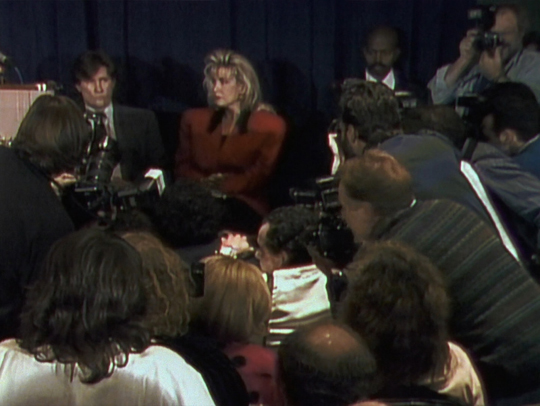

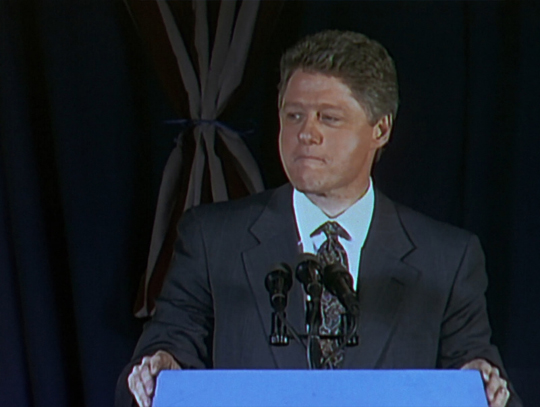

The War Room (1993), by Pennebaker and his wife and collaborator Chris Hegedus, is one of the last great examples of the genre, made just before the digital media wave broke. It almost evokes a feeling of nostalgia in its presentation of the emotional element in politics, the tension between ideals and human fallibility; looking at the crises the Clinton campaign faced in its early days (accusations of marital infidelity, draft-dodging), it seems virtually incom-prehensible that the Arkansas governor went on to win the Democratic nomination and then the Presidency itself. It was still possible in those slower media days to contain and control image in ways which are unthinkable now when image is at the mercy of countless “sources” that spread lies, distortions and occasional damaging truths through the Internet and social media. In today’s climate it’s almost impossible for a mere human being to stand up against the onslaught, hence the messianic tone of the Obama campaign in 2008, with the subsequent sense of deep disappointment when he turned out to be just a man after all, with weaknesses and blind spots which made it impossible for him to single-handedly transform (save) the nation.

The excitement around Bill Clinton in 1992 was more like that which greeted John Kennedy in 1960, a sense of youth, intelligence, enthusiasm and a promise to shake up Washington in realistic as opposed to magical ways.

What The War Room focuses on is the ways in which this narrative was shaped by the campaign team led by strategist James Carville and media director George Stephanopoulos, and even 20 years later, the film manages to convey the breathless excitement of the campaign and election and, remarkably, despite the fact that the result is now long-gone history, The War Room still somehow creates an air of suspense around the outcome – a sure sign that there’s more going on here than mere observation, the objective recording of events. Hidden behind the ragged immediacy of what we see, is a very skillful creative hand (or rather hands) constructing a thriller out of what were apparently highly problematic materials.

Pennebaker and Hegedus had long wanted to make a film about “a man becoming the president”, so when naive and enthusiastic producers R. J. Cutler and Wendy Ettinger approached them about doing a film on the 1992 campaign, they were warily excited. The keys that would unlock the project would be money and access. Access turned out to be the bigger problem. The Bush campaign turned the filmmakers down flat; Ross Perot couldn’t make up his mind whether he was running or not; and the Clinton people were too busy to return calls.

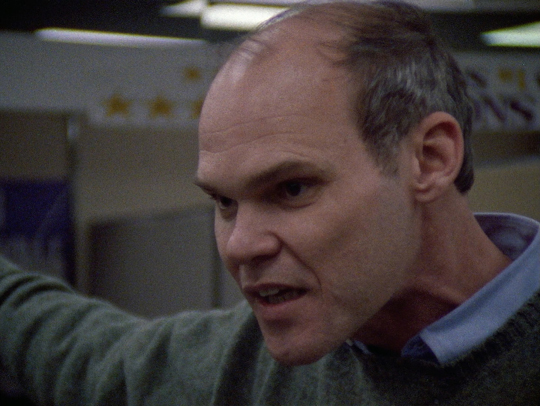

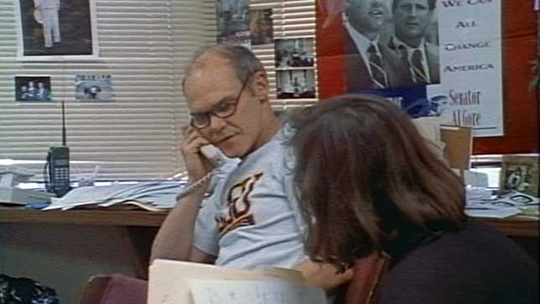

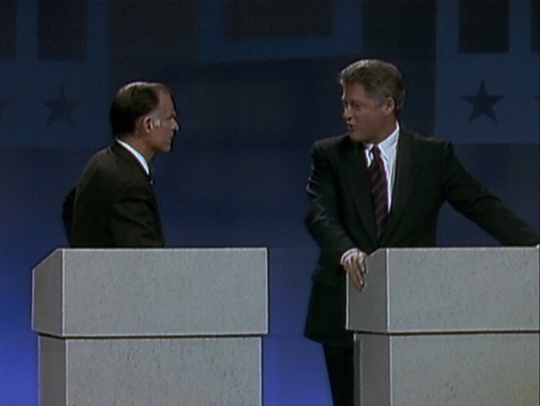

Persistence got the filmmakers permission to film at the Democratic National Convention in New York, but there was no way to get close to the candidate. What Pennebaker and his team did discover, however, was the tag team of Carville and Stephanopoulos, a pair that might have been put together by the savviest of casting directors. Totally unlike each other, they came together as a perfect unit, establishing what came to be known as the war room in Little Rock, Arkansas, the nerve centre of the campaign, monitoring on-going events and responding moment by moment to maintain control of their narrative.

Pennebaker and Hegedus found themselves admitted to this inner sanctum, but cut off from Clinton himself as he went out on the road for the gruelling campaign. Frustrated by their limited perspective, they felt that there was little chance of pulling together a successful film. But while they missed so many of the big moments, what they did manage to get was a close look at the internal processes of a campaign which was rewriting the way politics was done. And once they got into the editing room and started working with the material, they discovered just how powerful that material was and just how significant these new media-savvy players were as they discarded the standard strategies which both parties had held to for decades. Seamlessly fleshed out with material obtained from other filmmakers and from television news sources, The War Room ended up a kind of primer for the ways in which political campaigns and speeded-up media formed a symbiotic relationship in the creation of the myths which have become essential to win an election.

While the film itself still stands as a significant, and highly entertaining, document, what makes Criterion’s new 2-disk DVD (also available on Blu-ray) so valuable is the wealth of contextual material contained in the extensive supplements. There’s a feature-length retrospective documentary by Pennebaker and Hegedus from 2008, Return of the War Room, in which the filmmakers and their subjects look back on the groundbreaking campaign and the role of the media in it. Interestingly, this is a standard talking-heads piece, quite unlike the films the pair are famous for. Return captures both the sense of excitement from the time as well as a rueful wariness about where things have gone in the intervening 20 years; perhaps what stands out as most remarkable is the sense that there was a time when Democrats and Republicans could disagree fiercely but still connect with each other on a shared conceptual plain, exemplified here by the remarkable long-standing relationship between Carville and Mary Matalin, the deputy campaign manager for George Bush in 1992. They were dating during the campaign, and subsequently married and had two daughters. It’s virtually impossible to imagine something comparable happening today.

The supplements also include a lengthy four-way conversation between Pennebaker, Hegedus, Cutler and Ettinger in which they recall the difficulties of putting the project together and the sense of frustration that stayed with them right through the production. There are additional interviews with co-producer Frazer Pennebaker; cameraman Nick Doob (whose work on election night essentially saved the film by providing a genuinely emotional conclusion when the production failed to get close to Clinton at the moment of victory); and the campaign’s pollster Stanley Greenberg, about the ways in which political polling has evolved since the early ’90s.

Visually, Criterion’s hi-def transfer still looks very rough, not surprisingly as the film was shot on 16mm with nothing more than available light, the primary material fleshed out in the editing with TV news video. Although shot in chaotic conditions, it seems remarkable just how nuanced The War Room is, with Pennebaker and his crew capturing so many essential details of character and situation. The film and the supplements offer powerful lessons for anyone thinking of making a documentary, illustrating the complex interplay of contingency and persistence on location, and creativity in the editing room.

Comments