Entering Other Worlds, part 1

Watching Betrand Tavernier’s sombre, moving Death Watch (1980) recently, I started wondering about mainstream filmmakers who tried their hand just once at science fiction. While Tavernier’s film fits in with the humanistic themes which run through his work, was there a similar thematic consistency in other directors’ forays into the genre?

Shot mostly on bleak English locations, there’s nothing futuristic about the design of Death Watch; the sci-fi element resides purely in the central concept. This is also true of the films of more than half the directors who immediately came to mind – Jean-Luc Godard, Francois Truffaut, Rainer Werner Fassbinder, Elio Petri, Alfred Hitchcock and Abel Gance. Others were more overtly fantastic – Donald Cammell, Robert Altman, David Lynch, Andrzej Zulawski. I’ve only seen clips from Gance’s La fin du monde (1931), which counts as one of the first (if not the first) global catastrophe movies, with the world facing destruction by comet (Philip Wylie and Edwin Balmer wrote their novel When Worlds Collide two years after the original French release, but a year before the truncated American version).

Science fiction at its best has always been a vehicle for commenting on the contemporary world and human behaviour in relation to technology. Not surprisingly – after all the tradition goes back at least as far as Lucian’s True History in the 2nd Century – satire is a fairly common element: Godard’s Alphaville, Fassbinder’s World on a Wire, Petri’s The 10th Victim, and to some degree even Truffaut’s Fahrenheit 451 and Zulawski’s On the Silver Globe. There’s an apocalyptic note in Hitchcock’s The Birds, Altman’s Quintet, and again to some degree Godard’s Alphaville and Truffaut’s Fahrenheit 451. Of my limited sample, only Robert Altman in Quintet, David Lynch in Dune and Zulawski in On the Silver Globe go for a grander scale, conjuring up future, alien worlds more in keeping with what an average viewer would think of as sci-fi (though we could include Stanley Donen’s bizarre and silly Saturn 3 [1980] and Walter Hill’s disastrous Supernova [2000] if they were worth talking about).

Death Watch (Bertrand Tavernier, 1980)

Based on a novel by British writer D.G. Compton (I’d have loved to make a movie of his Chronocules, one of the best time travel novels I’ve ever read), Tavernier’s film prefigures reality TV by a couple of decades. In the near future, when death by disease has been all but eliminated, TV producer Vincent Ferriman (Harry Dean Stanton) seeks out someone with a rare terminal illness and finds Katherine Mortonhoe (Romy Schneider). She signs a contract to allow him to follow her with cameras and broadcast her sickness and death, but when she gets the money she runs out on him.

Ferriman convinces cameraman Roddy (Harvey Keitel) to have his eyes replaced with cameras and sends him after her. The film becomes a kind of road movie, with Roddy and Katherine forging a wary friendship as she makes her way to see her estranged husband Gerald (Max Von Sydow). Katherine doesn’t know that every intimate moment between them is being broadcast to a large, voyeuristic audience, and Roddy gradually comes to question his own part in the invasion of her privacy.

Most of Tavernier’s work deals with the psychological and emotional states of characters who find themselves in stressful circumstances, whether it be war (Capitaine Conan [1996], Life and Nothing But [1989], Laissez-passer [2002]), murder and crime (The Clockmaker [1974], Coup de Torchon [1981], L.627 [1992]), or the looming prospect of personal mortality (Daddy Nostalgie [1990], ‘Round Midnight [1986], and Death Watch). Tavernier is one of the great humanist filmmakers, an heir to Jean Renoir, so it’s not surprising that Death Watch is so deeply concerned with its characters rather than the technology which sets the story in motion.

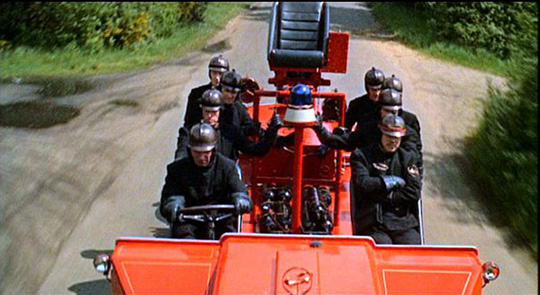

Fahrenheit 451 (Francois Truffaut, 1966)

Throughout his almost thirty-year career, Francois Truffaut worked in a number of different genres – mystery, romance, social realism, at times tinged with surreal touches – but only in Fahrenheit 451 did he attempt to create another world. Like Tavernier, he chose to make his one sci-fi film in English, a slightly puzzling choice as he was very limited in the language. Perhaps it was a way of increasing the distance from the more familiar world in which his other films were set.

Ray Bradbury’s celebrated source novel is actually more allegory than true science fiction, a lament for what he saw as the decline of the written word under the onslaught of mass media. Its story of a fireman whose job it is to seek out and burn books works better on the page than on the screen, particularly when presented as here in a more or less naturalistic style. Given concrete form, the silliness of the book’s conclusion is all too apparent: a cult of people who give up their lives to “become” books, erasing their own identities in order to embody classic texts rather than standing up to the abhorrent status quo by living and writing their own stories. The implication is that all creativity resides in the past, that people in this society are mere empty vessels waiting to be filled … the only question being what’s going to be poured into them, the vacuous nonsense offered by 24-7 television or the words of a long-dead writer. The ending of the film, rather than offering the inspirational vision which was no doubt intended, makes these people’s sacrifice appear futile and depressing.

But where the film really fails is on the level of execution. Stranded without his own language, Truffaut appears helpless to draw engaging performances from his cast. Oskar Werner, who had starred in Jules and Jim a few years earlier, is dull and passionless as Montag, the supposed rebel, while Julie Christie is adrift in an inexplicable dual role as the fireman’s wife Linda and his enticing neighbour Clarisse who awakens him to what’s wrong with the world. Only the great Cyril Cusack as Montag’s commander, a villain with more than a passing resemblance to O’Brien in Nineteen-Eighty-Four, manages to invest his character with energy.

The one saving grace is Nicolas Roeg’s photography, giving the sterile future world a disturbing presence which is otherwise missing from the film.

Alphaville (Jean-Luc Godard, 1965)

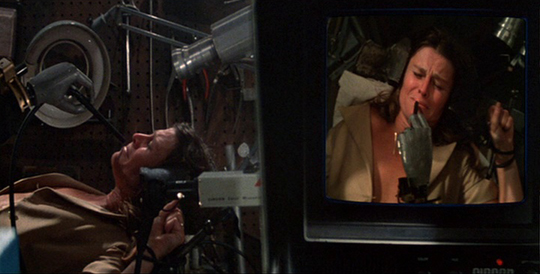

& Demon Seed (Donald Cammell, 1977)

Jean-Luc Godard and Donald Cammell took two very different approaches to artificial intelligence. Godard’s Alphaville, une étrange aventure de Lemmy Caution filtered pop culture pulp through the satirical lens of Fritz Lang’s Metropolis to present a city enslaved by an inhumanly rational super-computer, while Cammell’s Demon Seed adapted a pulp novel by Dean R. Koontz into a character study about a computer’s acquisition of self-awareness and humanity.

Godard famously mocks the genre by having protagonist Lemmy Caution (Eddie Constantine) travel interstellar distances to the city of Alphaville in a Ford Galaxie. As he arrives in contemporary Paris, the city’s modernist architecture takes on a fantastic dimension. Raoul Coutard’s rich black-and-white images easily convince the viewer that this is some kind of alternate reality (in the same way that George Lucas later transformed existing locations in the San Francisco area into a bleak future world in THX 1138 [1971]).

Godard’s wit and visual style invest the (deliberate) genre cliches – the mad scientist, the powerful computer, the conflict between love and reason – with something like pop poetry. The greatness of Alphaville lies in the fact that it could only exist as film, a unique fusion of sound and image that results in something far more complex and beautiful than the sum of its simple narrative parts. Alphaville fits very well into Godard’s practice of playing with, tearing apart and reconstructing genre, artfully transcending its source materials.

Cammell’s Demon Seed is a more conventional work, and far more conventional than the director’s first feature, Performance (1970), which he made with Nicolas Roeg seven years earlier. The film didn’t make much of an impression when it was released, partly because of its pulpy narrative, partly because a lot of people were disappointed that it wasn’t another Performance. But it’s actually one of the most interesting (and in at least one respect problematic) “evil computer” movies ever made.

Researcher Alex Harris (Fritz Weaver) has been developing an organic computer which he names Proteus. In true pulp fashion, the machine takes complete control of the scientist’s fully automated futuristic house. As Proteus develops self-consciousness, it observes Harris and his somewhat estranged wife, child psychologist Susan (Julie Christie again), and begins to assume certain human intentions. Proteus seals the house, imprisoning Susan. What follows is the trickiest part of the narrative: using the various devices available to it in the automated house, the computer essentially rapes Susan, artificially impregnating her. She gives birth as the machine is destroyed, but the child, a human-computer hybrid, now embodies Proteus’s consciousness.

Demon Seed deals with the consequences of investing a machine with self-conscious intelligence. Where the film differs from many other such stories is in what the machine does with that intelligence. Certainly, Proteus behaves in harmful ways – killing Harris’s assistant (Gerrit Graham) and subjecting Susan to a form of sexual violence. But the machine’s motives are not control and dominance (like HAL in 2001: A Space Odyssey [1968] or the defence super-computer in Colossus, The Forbin Project [1970]), but survival, and in particular survival in a very human form, through producing a child to live on after the machine’s own personal death.

As Cammell made only four features in his sporadic and troubled career, it’s hard to generalize beyond his tendency to be drawn to stories infused with psychological uncertainty and the human struggle to figure out who and what we are and what our relationship to the people around us truly is. In that respect, Demon Seed, for all its pulpy elements, seems just as personal a project as Performance, White of the Eye (1987) and Wild Side (1995).

Comments