Entering Other Worlds, part 2

When I mentioned to a friend that I was writing these posts about one-off sci-fi movies by mainstream filmmakers, he pointed out that I’d left Norman Jewison off the list. I readily pleaded guilty, my only excuse being that I’d originally made the list off the top of my head and hadn’t bothered to follow up with any more systematic research. But the truth is, Jewison’s Rollerball (1975) probably slipped my mind because he’s a director without a distinctive personality, a competent industry professional who’s made a few notable movies along with a lot of earnestly dull, well-meaning liberal “issue” features. Which is not to say I didn’t enjoy Rollerball. In between the dull scenes of corporate scheming, with avuncular John Houseman manipulating jock James Caan for financial gain, the three big action sequences depicting the brutal “sport” of Rollerball are dynamic and entertaining. I actually went to see it in the theatre several times back in 1975, and have seen it a number of times on video since – but it doesn’t stand up with anything like the interest of the other films on my list.

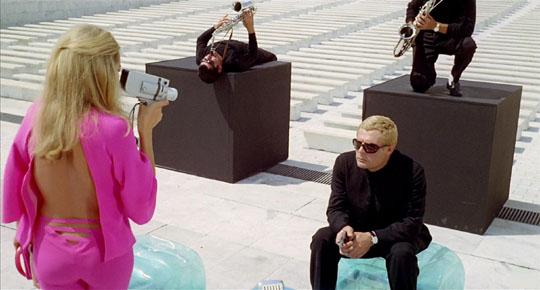

The 10th Victim (Elio Petri, 1965)

Elio Petri’s comedy shares a core theme with Rollerball: given the violence embedded in human nature, perhaps wars can be replaced by “sports” in which death is the penalty for losing. Of course, it’s an argument as demonstrably false as it is appealing – if only a few can be sent to fight and die, the rest of us can sit on the sidelines and enjoy the spectacle in comfort without any risk of our lives being unpleasantly disrupted. The Romans were famous for their bloody gladiatorial games, but that didn’t seem to have any effect on the endless colonial wars the empire fought in Europe and the Middle East. Of course it’s true that there’s a violent streak in human nature, but the enjoyment of spectacle has completely different roots from the fighting of wars, so trying to replace one with the other isn’t feasible.

However, the idea has a narrative appeal both as satire and allegory. Although it affords opportunities for pulpy exploitation (Death Race 2000 [1975]), from Peter Watkins’ The Gladiators (1969) to Daniel Minahan’s Series 7: The Contenders (2001) to Gary Ross’s The Hunger Games (2012), this mini-genre has provided ground for political, social and psychological commentary. All of which makes The 10th Victim a bit of a disappointment.

Based on a Robert Sheckley short story called The Seventh Victim, the film depicts a future world in which war has been replaced with an organized hunt whose contestants, alternately designated as hunters and prey, stalk each other through cities, their progress watched by a global audience. Petri was an intelligent leftist filmmaker, whose best work incisively dissects contemporary culture and politics (his masterpiece Investigation of a Citizen Above Suspicion [1970] uses a thriller framework to examine the nature of power in an increasingly fascist society); in The 10th Victim he worked on the script with long-time collaborator Tonino Guerra (who also worked with Fellini, Antonioni, Rosi and Tarkovsky among others), as well as Ennio Flaiano (co-writer of La Dolce Vita, 8½, La Notte), and yet this team managed to transform the social satire into romantic fluff about victim Marcello (Marcello Mastroiani) and hunter Caroline (Ursula Andress) falling in love as they try to kill each other.

The film’s chief interest now is its gaudy sense of design, a pop art look that links it to the likes of Roger Vadim’s Barbarella and Mario Bava’s Danger: Diabolik (both 1968), and also to some degree Fassbinder’s Welt am Draht, with the extremes of contemporary design now looking like garishly camp futurism. (In the latest issue of Video Watchdog [#168], Tim Lucas posits an entire genre built around this kind of design, which he designates “continental op”.)

Although disappointing in respect to what it might have been, and certainly a trivial footnote to Petri’s career, The 10th Victim is nonetheless more entertaining than Jewison’s movie.

World On A Wire (Rainer Werner Fassbinder, 1973)

The rather terrifyingly prolific Rainer Werner Fassbinder (more than forty features in sixteen years, before his death at 37) was obsessed with dissecting German society and history from a (politically and sexually) radical per- spective. His films are angry, satirical, sometimes technically rough (he worked very quickly), and often richly elaborate in style. Reputedly difficult to work with, it’s not surprising that he burnt out so young.

During his career, Fassbinder, unlike most of the other big names in the New German Cinema, took advantage of the opportunities offered by adventurous television executives, completing more than a dozen TV projects in the ’70s, including his epic 15-hour masterpiece Berlin Alexanderplatz (1980). All of these projects also received theatrical releases, except for one – Welt am Draht (World On A Wire, 1973). This also happened to be Fassbinder’s sole foray into science fiction, a two part adaptation of Daniel F. Galouye’s 1964 novel Simulacron 3.

Galouye’s remarkably prescient novel deals with a project to create a virtual world inside a computer so detailed that the simulated inhabitants have their own consciousness. The purpose is corporate market research. But in creating this simulated world, Hannon Fuller, the computer’s inventor, comes to realize that his own world is probably a simulation created in another, “real” world above. The story’s plot follows the mysterious death of the inventor and the re-discovery of this truth by Douglas Hall, his replacement as project head.

The influence of this novel is clearly apparent in the Wachowski Brothers’ flashy Matrix movies (1999-2003), but was also the source for Josef Rusnak’s underrated and neglected The Thirteenth Floor, which had the misfortune to be released around the same time as The Matrix. (And speaking of The Matrix, it bears mentioning that in Fassbinder’s film people can plug into the system and enter the virtual world as an active character, and that telephones play a part in getting back out again …)

Fassbinder’s Welt am Draht follows the novel quite closely, although it replaces Galouye’s distant future with a contemporary ’70s environment with few sci-fi trappings. Following Godard’s lead in Alphaville, Fassbinder used Paris to represent his alternate reality, a city which at the time was undergoing massive development, with signs of construction apparent everywhere. This subtle sense of a world under construction serves the narrative and its themes well.

This 3½ hour film is one of Fassbinder’s most playful. In making what he viewed as a popular, commercial project, he managed to address many of his usual themes, but with a much lighter touch. In structure it’s essentially a thriller, with Klaus Lowitsch an appealing and sympathetic protagonist (renamed Fred Stiller) who finds himself going a little mad as his investigation into the death of his boss, renamed Henry Vollmer (Adrian Hoven), leads him to doubt the reality of his own world; the more certain he becomes, the more dangerous his situation is. When problems develop with virtual characters in the Simulacron world, programmers erase them; it becomes apparent that the same thing is happening in Stiller’s world and forces are at work to eliminate him because he knows too much. This results in one of the best of the 1970s paranoid thrillers, shot through with quirky humour and a deep sense of existential unease.

Despite the fact that the film was shot quickly (in the fascinating documentary Fassbinder’s “World on a Wire”: Looking Ahead to Today – included on Criterion’s new Blu-Ray and DVD editions, as well the region-2 DVD from Second Sight Films – cinematographer Michael Ballhaus recalls that it was either four or six weeks), Welt am Draht is one of the director’s most visually elaborate films, the apotheosis of his love of mirrors and reflecting surfaces. In this case, that visual tendency is completely justified thematically as the environment of the film fragments into unstable surfaces which suggest a world without real substance, in which the characters are pieced-together constructs. The film is full of remarkable camera moves which must have been extremely complicated to execute without revealing camera and crew in the maze of glass and mirrors created by designer Kurt Raab (who also plays the sinister Mark Holm).

Fassbinder’s tendency to elicit affectless performances from his actors also works to the film’s advantage; the characters often behave like blank automatons, caught at the corners of the frame as if passively waiting to be engaged by another character before they come to life. The effect is oddly unsettling, even comic at first (the party scene in which we first encounter Stiller is a masterpiece of satirical comedy), but as the story progresses the sense of unreality becomes more pronounced and increasingly confirms the legitimacy of Stiller’s paranoia.

The seemingly happy ending, in which Stiller is brought out of the simulation by the woman who had claimed to be Vollmer’s daughter but is in fact a visitor from the world above, has echoes in the Matrix films because, although we only get a very brief glimpse of the “real” world, it appears to be much less appealing than the simulation he has left behind.

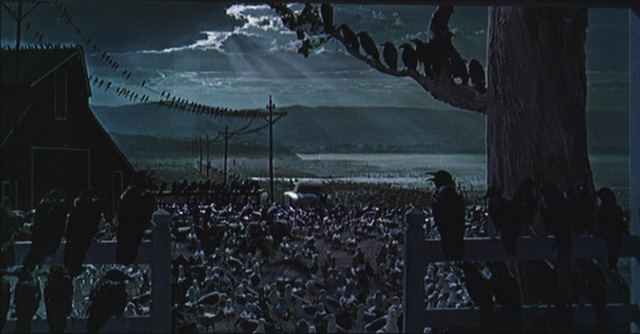

The Birds (Alfred Hitchcock, 1963)

I suspect that I’d get an argument from some people about calling Alfred Hitchcock’s The Birds science fiction, but I think I’m justified. One of Hitch’s masterpieces, this is the greatest and most mysterious of the nature’s revenge movies, and it could serve as a textbook of narrative structure. The film, adapted by Evan Hunter from Daphne Du Maurier’s novella, begins very lightly, much like one of Hitchcock’s romantic-comedic thrillers (think Rear Window, It Takes a Thief), with hero and heroine meeting cute in a San Francisco pet shop. She, Melanie Daniels (Tippi Hedren), is an irresponsible socialite; he, Mitch Brenner (Rod Taylor), is an attorney … and she amuses herself by playing a pointless practical joke on him which backfires. Of course, his disdain hooks her and she pursues him to Bodega Bay, the small town on the coast where he lives with his mother Lydia (Jessica Tandy) and younger sister Cathy (Veronica Cartright).

On one level, the film is working out the dynamics of the developing relationship between the two, under the hostile eye of the mother and the sad rather than jealous eye of local teacher Annie (Suzanne Pleshette) who loves Mitch, but knows he’s out of her reach. An entire film could have been made about these characters and their situation. But something else begins to intrude. As Melanie crosses the bay in a small boat, a gull swoops down and gashes her forehead. It’s the first sign that something is unbalanced, that the personal story won’t be allowed to follow its natural course. As the bird attacks escalate, Lydia, who has a deeply neurotic attachment to her son, blames Melanie for bringing this danger into their lives.

Unlike most nature’s revenge movies, The Birds refuses to offer a clear-cut explanation of events, so Lydia’s suspicion might be as valid as any other. In the great diner scene, with a group of frightened people trapped by the latest massed attack out in the street, everyone has a theory, but no one really knows anything. The lady ornithologist insists that birds are incapable of banding together to launch a concerted attack; the drunk punctuates what everyone says by repeatedly asserting that “it’s the end of the world.” This is not the usual revenge for our bad behaviour in polluting the environment – or for that matter sunspots or alien intervention – but rather an expression of our deep vulnerability, an existential dread arising from a glimpse of the immense power of non-human nature.

The diner scene climaxes with the explosion of the gas station across the street, which is followed by one of my favourite shots in all the movies I’ve ever seen. As the gas tanks go up in a giant fireball, Hitchcock cuts to a god’s eye view of the town, the flames bright in the centre, but absolutely silent from this height. There’s a moment of uneasy peace, a sense of just how small and insignificant the human life below really is … and then a gull glides quietly into frame, and then another, and we can feel the full force of our vulnerability and the complete implacability of the natural world.

The element of fate and human fragility here is what links The Birds so firmly with much of Hitchcock’s work. So many of his films involve ordinary, likeable people in extraordinary situations which test their character and transform their view of the world. But in his other thrillers, this is always brought about by human agency – the hero or heroine find themselves embroiled in a criminal plot, security stripped away, on the run from villains and often from the police as well. In The Birds, this process is laid bare by the seemingly arbitrary, even abstract nature of the threat which undermines Mitch and Melanie’s unremarkable lives. In a way, then, The Birds is the quintessential Hitchcock film, the one which most clearly states his thesis about the abyss we’re all perched on the edge of.

I’ve no doubt that some viewers are irritated by Melanie’s eventual descent into a kind of helplessness, almost catatonia, after she’s attacked in the attic. It’s a psychologically plausible development, but does suggest that the woman is weaker than the man when faced with what seems to be a hopeless situation. I suspect that this was an influence on Barbara, the Judith O’Dea character in Romero’s Night of the Living Dead (1968), who retreats into catatonia once the hopelessness of her situation becomes clear. The fact that these retreats from reality tend to irritate the viewer has more to do with conventional narrative expectations than questions of psychological realism.

I first saw The Birds in the late ’60s on a black-and-white TV. While I’d been forbidden to watch Psycho not long before, The Birds was deemed suitable viewing for an adolescent. I recall one of my classmates complaining the next day that the ending had been cut off. He insisted that he’d seen it before and that the army had come in, using the children for bait, and killed all the birds with flamethrowers. An interesting example, perhaps, of the mind’s need to get some kind of narrative closure. That evening I sat down and wrote out the story of the film in as much detail as I could remember so that I could hang on to it, not knowing when or if I’d ever get another chance to see it.

The final enduring mystery is just what the heck has happened to the Blu-ray which was announced several years ago and continues to be listed on Amazon as “available for pre-order”, though there’s no sign of an actual release date. One can only hope that the delay is due to Universal doing a monumental restoration from the original negative.

Comments