Entering Other Worlds, part 3

My final brief look at one-off science fiction projects by mainstream filmmakers deals with three films which conjure up alternate worlds (or universes) with differing scales of resources.

Quintet (Robert Altman, 1979)

Robert Altman was one of the most eclectic directors of the ’70s, with works as varied as M*A*S*H (1970) and Nashville (1975), The Long Goodbye (1973) and McCabe & Mrs Miller (1971). Being both prolific and often critically and commercially successful, he was able to play and experiment with styles and genres, resulting in oddities like the quirky Brewster McCloud (1970), lyrical Images (1972), and mysterious 3 Women (1977). Some of these efforts were not well-received, but Altman usually bounced back with something more palatable to critics and audiences: he followed Brewster with McCabe, Images with The Long Goodbye, 3 Women with A Wedding (1978) …

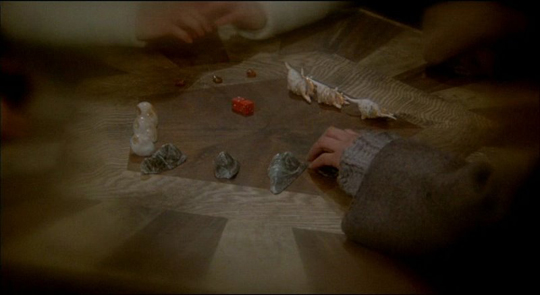

And then he made Quintet (1979), one of his most poorly received films. Bleak, obscure, and set far from the more or less real world of his usual work, people didn’t quite know how to take it. When it came out, I was in my mid-20s and a long-time sci-fi fan, so I was quite naturally open to anything that offered a glimpse of another world … and that’s exactly what Altman did with Quintet. It seemed to me that, like the best of science fiction, he took his premise and simply inhabited it, wasting no time in explanations or exposition, simply dropping the audience into an ice age where we follow a nomadic couple as they arrive in a city mostly buried by snow and ice. That couple, Essex (Paul Newman) and Vivia (Brigitte Fossey, who began her career in 1952 with Rene Clement’s magical Jeux interdits), find themselves caught up in what seems to be the main pastime of the city’s inhabitants, gambling on a dice game called Quintet. It gradually becomes apparent that the game is being played in real life as well as at the gaming table, with losers dying.

The film is alienating to a degree because of its refusal to explain, to make things easier for the audience. We never really know quite what’s going on. We stay at a distance as observers, but as in his other films, Altman evokes a world fully inhabited by its characters. And that world, a monochrome frozen wasteland with no possibility of escape (shot in the middle of a harsh winter at the futuristic site of Expo ’67 in Montreal), is beautifully realized by production designer Leon Erickson and cinematographer Jean Boffety. What Quintet lacks in narrative engagement, it more than makes up for in atmosphere. The first time I saw it, I stayed in the theatre and sat through it twice (you could still do that in those far-off days!), and I went again the next week, just to experience the otherness of the movie’s world.

Although so firmly set in that other world, Altman approached the film in the same way as his other work, naturalizing the frozen future as he had naturalized the frozen past in McCabe. The depiction of a world whose heart is essentially unknowable to the people who inhabit it is something the film has in common with most of the director’s work – the murderous game of Quintet something like war in M*A*S*H, capitalism in McCabe, show business and politics in Nashville …

On the Silver Globe (Na srebrnym globie, Andrzej Zulawski, 1988)

Altman always strived for a kind of naturalism in his work, famously with his complex, multi-character scenes packed with overlapping dialogue, forcing the viewer to pick out what might be significant just as we have to in the crowded world we actually inhabit. It would be difficult to find a filmmaker whose technique was more of a polar opposite than Andrzej Zulawski. No matter how rooted in the real world a Zulawski film might be – the struggle of an ageing actress with her own career decline in L’important c’est d’aimer (1975), the bitter disintegration of a marriage in Possession (1981) – he pushes the narrative to extremes with his insistence on embodying emotions in physical, visual terms. This gives much of his work an air of hysteria, as if the camera itself were going mad with whatever is tormenting the characters on screen.

A lot of people find Zulawski’s work to be “too much”, overwrought, pretentious. Although I can’t say I like all of his films (for instance, L’amour braque [1985] seems to me to represent everything Zulawski’s detractors accuse him of), I’ve been fascinated with his work since my first encounter with Possession in the early ’80s. His aggressively mobile camera virtually dragged me into the emotional insanity of a couple living in Berlin (Sam Neill and Isabelle Adjani) whose painful relationship seems to overwhelm the world in which they live. It’s an uncomfortable film and for that reason repellant to some viewers, but I found it one of the most convincing creative expressions of an emotional state I’d ever encountered. With Zulawski, you can’t sit back and observe, you can’t maintain an intellectual critical distance; either you give in to him and plunge into the states of mind he conjures up, or you simply have to turn away.

But that doesn’t mean that there aren’t ideas and themes in his work which can be discerned and interpreted. It’s just that you usually have to deal with those levels after you’ve emerged from the experience of the film.

Although there are fantasy and magic realist elements throughout Zulawski’s filmography, On the Silver Globe (1977-88) is his sole science fiction movie. Adapted by the director from a trilogy of novels written by his great-uncle Jerzy Zulawski in the early 1900s, the film was never completed because part way through production a newly appointed Polish film bureaucrat suddenly decided that it was a veiled criticism of the communist establishment and ordered the project to be shut down. Sets and costumes were destroyed, and Zulawski left Poland for France. After making three films in the west, things had loosened up in Poland by the late ’80s and the director returned to try to salvage what would have been his biggest film.

Although it runs 2¾ hours, On the Silver Globe remains an unfinished work, pieced together from what had been shot a decade earlier, the gaps filled with readings from the screenplay presented over urban and natural images which inevitably evoke memories of Tarkovsky, particularly Solaris (1972). All this gives On the Silver Globe a strange ambiance which it may well not have possessed if it had been completed as originally intended. Given the film’s ambitious themes, it may even work more effectively in its current form – more contemplative and essayistic than narratively coherent.

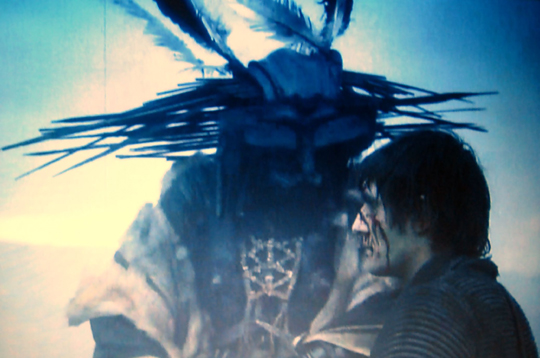

The grand theme of the film is the role of religion in the formation and shaping of human society. Three astronauts survive a crash landing on an alien world and in that great (and hackneyed) sci-fi tradition eventually give birth to a whole tribe (just like Adam and Eve) which develops its own belief system based on vague memories of Earth. When another astronaut arrives, he’s greeted as the prophesied saviour come to deliver the tribe from the demonic indigenous inhabitants of this world.

Impressive in scale and design, with wonderfully chosen locations to evoke a sense of otherness, Zulawski’s film sees religion as a form of madness that runs through history causing violence and pain even as it seems necessary to give form and meaning to social organization. In this partially crippled epic, the director takes the personal emotional and psychological extremes of his other films and applies them to human society as a whole.

Dune (David Lynch, 1984)

Like Zulawski’s film, Frank Herbert’s turgid epic also deals with religion and the ways in which it’s shaped by environment and social politics. Dune deals with two belief systems: the Bene Gesserit, which is something like a female-centric Catholicism whose millennia- long mission is to produce a male messiah; and a kind of Islamic messianism bred in the harsh desert conditions of Arrakis. The ironic core of the book is that the sisterhood’s messiah turns out to be someone who leads the desert-dwelling Fremen in a successful revolt against the imperial ruling system of the galaxy, which the Bene Gesserit have been manipulating for their own ends.

Readers familiar with this website will already know that I have a somewhat complicated relationship with David Lynch’s adaptation of Dune. Having spent six months in Mexico watching the production being shot, I’m disappointed by the crippled end result, but nonetheless love the movie for what is still visible there on screen. Which is to say that I like the film for its Lynchian elements while recognizing its failings as a narrative.

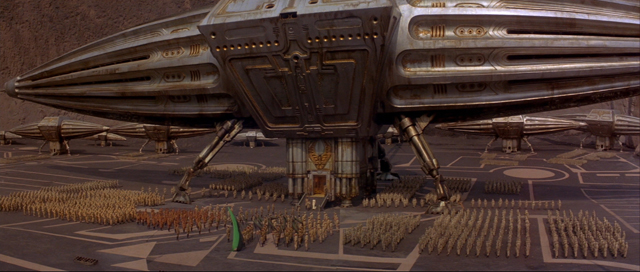

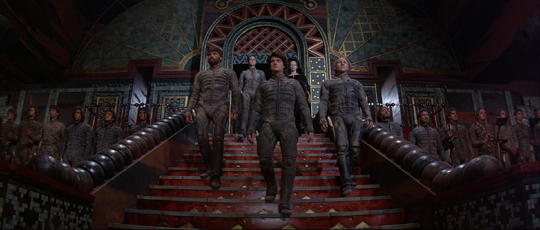

Dune is an anomaly in Lynch’s filmography and looking back it still seems remarkable that he was hired by Dino de Laurentiis to do the job. He had only two films to his credit, the very independent Eraserhead (1977) and the small but prestigious The Elephant Man (1980), and here he was being hired to write and direct one of the most expensive movies ever made, an epic faced with massive logistical problems and an intensely loyal and opinionated fan base. It was almost doomed to failure, but might have been better received if the distributor, Universal, hadn’t stupidly insisted on a two-hour running time. The book is large, complicated, and packed with plot and characters which demand a more expansive canvas, and anyone but a studio bean-counter would have recognized the necessity of more time to let the story breathe. Why they would back it to the tune of $40+ million and then ensure that it could never satisfy the fans is anybody’s guess. And so the narrative was gutted, leaving a dense, confusing monument to David Lynch’s design obsessions – the strangely anachronistic technologies which expand on the bleak industrial settings of Eraserhead and The Elephant Man, the fascination with biological functions and textures …

Despite its narrative shortcomings, Dune remains one of the most richly imagined screen fantasies ever made, immersing the viewer in its multiple worlds in a way that few movies do. The design of the film isn’t merely there to prop up the story (as in, say, Star Wars), but in a sense supplants story, becoming the meaning and purpose of the film. Like the drawings of Piranesi or the paintings of Bosch and Breughel, Dune offers an alternative way of seeing the worlds we humans create for ourselves. While most of Lynch’s work looks inwards, into his and his characters’ subconscious experiences, Dune looks outwards to the social, architectural and technological constructions we erect in order to manage our environments and control and manipulate one another.

It’s a pity that Lynch has all but disowned the movie. While it may not satisfy the book’s fans or please a general audience, it is nonetheless a unique and aesthetically rewarding accomplishment.

Comments