Flipside: the Art of Andy Milligan

There’s far more stuff in the world than any of us can ever have complete first-hand knowledge of, so we often have to rely on second- and third-hand information about things we haven’t yet encountered. This leads to a tendency to form opinions about things we actually know nothing about … and judging by a lot of on-line chat threads, many such opinions are fiercely held. When we do finally encounter something we’ve read or heard about and feel we have a fairly clear idea of, we may be surprised to find that we really didn’t have a clue and must quickly wipe away our certainty and replace it with something more in tune with reality. Or, conversely, we may continue to peer through that prior opinion and convince ourselves that what we see actually conforms to it.

One of the great benefits of DVD is the access the format has provided over the past decade or so to movies that were previously inaccessible, permitting us to test our received opinions. For instance, I now have a large collection of silent-era films which have changed much of what I thought I knew based on reading about the period when only Chaplin, Griffith, Keaton and Mack Sennett were readily available (usually in compromised, poor-quality prints run at the wrong frame-rate). It’s been remarkable to discover how quickly film techniques developed, giving the lie to the long-held myth that D.W. Griffith single-handedly invented everything from editing to the close-up and sophisticated narrative construction.

At the other end of the scale, DVD has offered a seemingly endless stream of exploitation movies, from Dwain Esper’s Maniac (1934) to virtually every direct-to-video slasher from the ’80s, with countless ’50s sci-fi, horror and juvenile delinquent dramas in between. While the basic drive underlying all exploitation is the same – offer the forbidden or offensive that respectable mainstream movies shy away from and a sizable audience will cough up the price of admission – as with any other type of movie the range of quality and degree of creativity in exploitation varies wildly. A prolific and talented filmmaker like Roger Corman can achieve a degree of respectability which gains him the power to nurture a remarkable number of promising young filmmakers (a respectability and power he has long-since squandered with a seemingly endless stream of wretched Sci-Fi Channel monster shows).

While never gaining Corman’s level of industry respectability, other low-budget exploitation filmmakers have achieved prominence for various different reasons. Ed Wood, tagged by the insidious Medved brothers as “the worst director of all time”, is a perennial favourite with people who like to feel superior and laugh at incompetence … though personally, I think he’s better and more interesting than that. A darker and more complex character than appears in Tim Burton’s charming Ed Wood (1994), there’s a fascinating derangement in much of his work which transcends the label “incompetent”. In the visual arts, there are people termed “naive painters”, untrained, lacking facility with now-accepted technical standards (what’s perspective?), but who nonetheless seem to be expressing something vital. If Wood’s films were merely incompetent, his appeal wouldn’t have lasted; while audiences laugh at him, it’s often due to the gap between his ambitions and his financial and technical resources. No matter how much of it was unconscious or accidental (read his dialogue on the page and it becomes a weird kind of absurdist poetry), for me Wood’s masterpiece Glen or Glenda (1953) is one of the great surrealist films, and I’d rather watch this ode to transvestism once more than take yet another look at Un Chien Andalou.

Interestingly, some viewers seem to respond more favourably to exploitation which is more calculated, less personal. Herschell Gordon Lewis deliberately set out to open a new niche in the market after nudie films became a glut. He sat down with producer David R. Friedman and listed all the things that the mainstream couldn’t do because of the production code and came up with “gore”. His Blood Feast (1963) offered the spectacle of women being disemboweled as part of a scheme by an Egyptian caterer in Miami to resurrect an ancient goddess. Despite production values and a level of competence that didn’t even rise to Ed Wood levels, the mere idea of such graphic mayhem was enough to make the movie a lasting hit … and the confirmation of an audience waiting for this kind of stuff opened the floodgates. We’ve been living with Lewis’s legacy for almost fifty years now.

Andy Milligan

All of which brings me around to Andy Milligan. Until recently, he was nothing more than a vaguely familiar name, someone lumped in with the likes of Ted V. Mikels (whose excruciating The Corpse-Grinders [1971] I sat through at a lunchtime screening at the University of Winnipeg in the late ’70s). I knew of Milligan only as yet one more incompetent working the bottom fringes of the business, turning out stupid, unwatchable crap. Which is why it came as a puzzling surprise to see the BFI announce the release of an Andy Milligan double-feature as part of their Flipside series. They’d previously released a variety of exploitation movies, but this seemed almost like a perverse challenge to their audience to see how far down into the cinema sewer they’d be willing to go.

I took the challenge, largely because I have a completist obsession (I have all the Flipside releases to date, except for Peter Watkins’ Privilege, which I already own in the excellent region 1 Project X edition). Having resisted reading the fat accompanying booklet before popping the Blu-ray (yes, Andy Milligan on a carefully restored hi-def disk!) into the player, I quickly found myself both puzzled and strangely captivated.

Milligan, having been very active – and surprisingly influential – in the New York underground theatre movement of the late ’50s and early ’60s, had turned to filmmaking with one of the first openly gay movies, the short Vapors (1965, available from the BFI on their compilation disk Encounters, and on Something Weird Video’s edition of The Body Beneath). He was quickly offered (very little) money to turn out a series of sex-themed quickies for the 42nd Street market. After several years of prolific production and frequent clashes with his backers, he accepted an offer from producer Leslie Elliot to go to England with a multi-picture deal to supply fodder for the private Compton Cinema Clubs chain.

Nightbirds (1968)

The first fruit of the agreement was Nightbirds, the focus of the BFI disk. This black-and-white feature apparently had only one public screening before disappearing into obscurity. Eventually, it wound up in the hands of Nicholas Winding Refn, who worked closely with the BFI to create this edition.

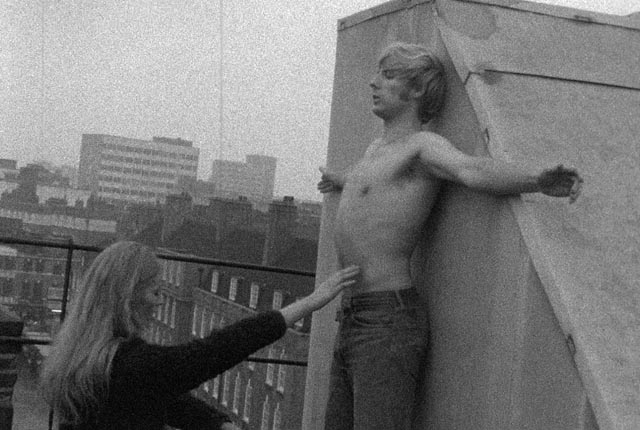

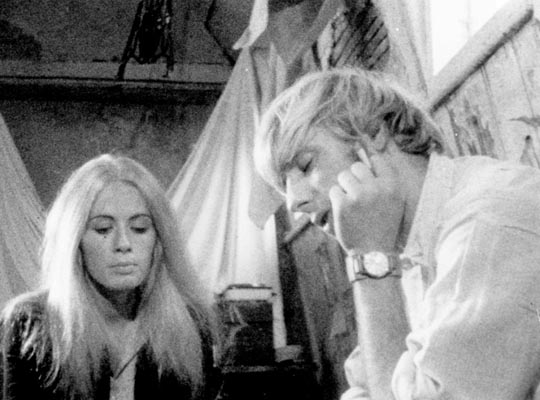

Nightbirds tells the claustrophobic story of young Dink (Berwick Kaler), whom we first meet throwing up on a London street, and Dee (Julie Shaw), a solicitous young woman who buys him a cup of tea, then takes him home to her room in an East End slum. For most of the film, we’re trapped in that room with the pair of them as their “relationship” shifts and wavers in ways it’s often hard to get a grip on. As I watched, I was never quite sure whether this ambiguity was a result of amateurish performances or in some way intentional. Many scenes are distinctly uncomfortable as the currents of sexual tension pull the characters together and just as quickly push them apart. It’s only in retrospect, at the end of the film, that things fall into place and it becomes apparent that for all its limitations, Milligan has conjured up an evocation of personality derangement and sexual pathology which would quite comfortably fit into a double-bill with Polanski’s Repulsion.

The technical limitations of the film actually serve its themes well. This, like all Milligan’s previous films, was shot on his second-hand Auricon, a 16mm camera which recorded sound directly onto reversal film. Without a separately manipulable soundtrack, Milligan was limited in terms of editing and developed a technique which used extended takes, at times with fairly elaborate hand-held movements. But it also produced the inevitable effect of a one-second silence at every cut (there’s a one-second physical lag between sound and picture on all films), a fact which calls attention to and emphasizes every cut, resulting in a perceptual fragmentation which underlines the often jarring psychological shifts in the characters’ behaviour.

What we have in Nightbirds is a story of sexual and gender insecurity driven by a predatory woman bent on possessing, controlling and ultimately destroying an uncertain man. This is apparently one of Milligan’s main themes, rooted in his own life as an aggressively homosexual man who had what appears to have been a pretty grim relationship with his own mother. (After watching the two movies on the disk and reading the accompanying booklet, I quickly tracked down a copy of Jimmy McDonough’s Milligan biography The Ghastly One, a fascinating, disturbing account not just of Milligan’s life but also of the New York underground milieu he operated in; it’s a great real-life monster story, the non-fiction counterpart to Brock Brower’s The Late Great Creature and Theodore Roszak’s Flicker.)

With its harsh photography (Milligan shot his own movies on short ends and scraps of film), expressive camerawork, unsettling performances and bleak view of human relationships, Nightbirds qualifies as a great piece of rediscovered underground filmmaking, as good as or better than much of what came out of the Warhol Factory. The Body Beneath, the second feature on the disk (and the second of five movies Milligan made in England in just over a year), is very different, a deliberate attempt at a more commercial feature made with the remains of the money from Elliot after Milligan parted ways with Compton Films following an unpleasant argument with Leslie’s father Curtis.

The Body Beneath (1968)

The Body Beneath is a vampire movie, which almost willfully rejects genre conventions – or perhaps simply ignores them out of disinterest. In sharp contrast to Nightbirds, it’s shot in vivid colour, the earlier film’s naturalistic look and use of bleak London streets replaced by an oddly imprecise temporal and physical setting. Much of the film was shot in and around a huge Victorian mansion in north London. Early scenes establish the story as set in the present-day, but once we get to the mansion, there’s a Hammer-like Gothic period ambiance. The story revolves around the Reverend Alexander Algernon Ford (effectively played by Gavin Reed) who happens to be an ancient vampire intent on reviving the tired family bloodline by recruiting some distant female relatives. The plan is a dismal failure, at least in part due to his obvious distaste for women. Meanwhile, the vampire clan fight among themselves about whether or not to uproot and seek new life in the United States, an idea which repulses the European traditionalists among them.

The Body Beneath doesn’t offer anything in the way of conventional horror movie scares, which is no doubt why it’s held in fairly low regard. But what struck me most was how similar it is to the films of Jean Rollin with its cloying atmosphere of hothouse decadence, the dreamy conflation of sex and death, and its ultimate sympathy for the vampires over the dull middle class human characters. Where Milligan differs most obviously from Rollin is in his almost puritan abstention from genuine eroticism.

As in Nightbirds, Milligan’s photography is often strikingly expressive – particularly in the sequence of the feast at which the vampires argue about the proposed move to the States (reminiscent, as Stephen Thrower suggests in the BFI booklet, of Kenneth Anger’s Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome). He had a sideline as a dress-designer (during his career, he owned several haute couture shops in various parts of New York and had a reputation as a creative designer) and the costumes in the film are inventive and colourful. Also as in Nightbirds, a streak of cruelty runs through the film, climaxing with the Reverend’s punishment of his hunchbacked servant (Berwick Kaler again), who gets crucified on a tree in the formal gardens.

From these two films, it seems clear that Milligan was disinterested in adhering to conventional forms, his rush to get the job done resulting in shortcuts which to a casual viewer might appear to be incompetence, but are actually an integral part of his creative drive. By McDonough’s account, much of Milligan’s later output is pretty wretched – he never rose to what most filmmakers would consider even a minimally acceptable budget level – but these two movies are well worth a look and they’ve inspired me to track down a number of other titles which are available on DVD. Perhaps I’ll write something more about him after I’ve watched a few of them.

Comments