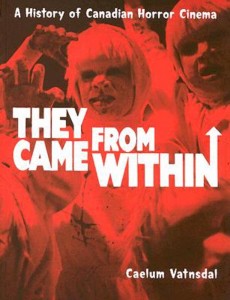

Book Review: They Came From Within by Caelum Vatnsdal

This is a review I wrote a few years back for Prairie Fire. A couple of reasons for republishing it here: 1) I don’t have a lot of time to write at the moment as I’m pushing to finish my documentary; 2) I recently ran into Caelum on the street and we had a chat about a very exciting book project he’s working on (which I can’t say anything about yet); and 3) the book is still in print and well worth seeking out.

They Came From Within: A History of Canadian Horror Cinema

by Caelum Vatnsdal

Arbeiter Ring Publishing

2004

256 pages

Amazon.ca

Amazon.com

“Canadian horror cinema is a cinema of moments, rich with unlikely imagery, baffling storylines and bizarre narrative twists. It is the home of defiantly unpredictable confluences (severed heads, disco dancing and Leslie Nielsen all in one movie, for example!). And largely illegible, usually accidental subtext.” (17-18)

In his entertaining and informative survey, They Came From Within: A History of Canadian Horror Cinema, Winnipeg writer, broadcaster and sometime film-maker Caelum Vatnsdal takes on the quixotic task of identifying and defining a specific genre of Canadian horror. Stretching back to the early days of silent film and The Werewolf (1913) and ranging through the sparse decades leading to the tax shelter years of the ’70s and ’80s and on up to the present, Vatnsdal’s effort is wide-ranging, indeed almost encyclopedic. But while there is an innate human preoccupation with creating categories and classes as a way of making the world we experience more manageable, the realm of art and popular culture presents some problems.

The first difficulty, perhaps insurmountable, is the issue of what constitutes “Canadian”. Is a Canadian film one made by a Canadian filmmaker, with Canadian money, regardless of content and/or setting? Is it one made in Canada, regardless of creative personnel and/or financing? Is it one with a specific Canadian location and/or characters regardless of who makes it or where it is made? (Fiend Without a Face [1958] was set in northern Manitoba, but shot in Wales by an English director!)

Of course, the debate about Canadian identity – and about the identity of Canadian film – has been going on for as long as anyone can remember and is not likely to be resolved in a book about largely disreputable low-budget movies. One of the book’s limitations is this difficulty of arguing for or delineating a specifically Canadian form of horror movie. All film-making in Canada has to contend with, or fight against, the power that US commercial film has in Canada, and by and large horror is the most commercial of genres, which only compounds the difficulty.

Equally fraught are the issues of genre itself. Of necessity, creating such a taxonomy involves singling out and privileging certain narrative and stylistic elements. What terms are chosen and how they are defined are things influenced by many factors, including the social, economic and aesthetic. The process of definition begins as an exercise in finding patterns among pre-existing works and then, once consolidated, becomes more prescriptive and judgmental (as is apparent from the critical and viewer resistance which often attends efforts to mix genres: people don’t know “how to watch” hybrids because they attend with preconceptions firmly in place).

Once proposed, a particular genre takes on a kind of organic life of its own: in time, usage solidifies our perceptions so that we automatically “know” the genre position of what we’re watching. And yet there remains something disreputable about genre, so we often separate more artful works from their genre moorings (Dreyer’s Vampyr [1932] isn’t horror, it’s a philosophical tale with a vampire in it). Genre becomes a filter which obscures other qualities in individual works. For instance, Christopher Frayling in his large book on the spaghetti western valorizes the interesting but dramatically unengaging Bullet for the General (Damiano Damiani, 1967) because he can read into it his political thesis, but dismisses with barely a mention the rich – in theme and metaphor – Keoma (Enzo G. Castellari, 1976), whose concerns exist on the level of personal/familial/racial psychology rather than class conflict.

Key to an understanding of genre is the tension between generic expectations and the desire to be surprised: adhere too closely, you bore; diverge too far, you frustrate expectations. At its most extreme this tension results in such things as the ludicrous attack in Variety on George Romero’s Night of the Living Dead: “this horror film … casts serious aspersions on the integrity and social responsibility of its Pittsburgh-based makers, distributor Walter Reade, the film industry as a whole … as well as raising doubts about … the moral health of film goers who cheerfully opt for this unrelieved orgy of sadism.” By 1968, horror was perceived as “for kids” and, as Roger Ebert pointed out in his column about the film (widely read as it was republished by the conservative Reader’s Digest), Romero’s film traumatized the kids whose parents thoughtlessly dropped them off for a Saturday matinee. Romero had “violated” the rules of genre by making something genuinely frightening instead of full of safe, generic scares and reassurance.

Perhaps here we might glimpse something of that elusive “Canadian” character: when an equally disturbing Canadian film was attacked by a mainstream critic a few years later (Robert Fulford on David Cronenberg’s Shivers [1975] in Saturday Night), it wasn’t so much the horror that was the problem as it was the public funding that went into it. Variety attacked Romero for being irresponsible; Fulford attacked the Canadian Film Development Corporation for irresponsibly supporting a degenerate filmmaker …

On top of these difficulties with the idea of genre itself, Vatnsdal posits a general resistance to the very notion of genre in Canadian film, a resistance founded in what he perceives as the rooting of Canadian culture in a pragmatic view of the world. (Here we are largely talking about English Canadian film; Quebec film is a whole other issue.) This pragmatism is reflected in film by the primacy of a naturalism or realism based on the documentary tradition represented by the National Film Board. Canada, Vatnsdal proposes, is a practical state of mind with a deep distrust of the imagination. This seems to be borne out to some degree by the history of feature film production in Canada, a tradition whose landmarks are such works as Don Shebib’s Goin’ Down the Road (1970) and Drylanders (NFB, 1963) by Don Haldane, who himself went on to tackle horror with less critical favour in 1971’s The Reincarnate.

Given this background, it is not surprising that genre film-making has not fared well in Canada. In addition, horror (like porn) is the most disreputable of genres because one of its primary aims is to subvert the intellect and elicit a purely physical, emotional response. This means that the genre’s defenders are often … well, very defensive. (This, however, doesn’t mean that a defense has to be limited to excuses: see, for instance, Carol Clover’s excellent and stimulating examination of the “slasher” sub-genre, Men, Women and Chainsaws [Princeton, 1992].)

There are many supplementary questions raised by these thoughts on genre which remain largely unaddressed by Vatnsdal: why do we like to be scared? What is the relationship between the desire to view transgressive narratives and the deeply conservative streak in the genre – the forceful re-establishment of the status quo, the reassuring finale? Was there a fundamental change in the genre in the ’60s when social and political upheavals made such reassurance problematic, producing the new generic tropes of the “final scare” and the unclosed ending? Or is the nihilism and despair implied by these mutations merely further evidence of an underlying conservatism?

But if They Came From Within is inconclusive as the blueprint for a genre, it has many other virtues. Vatnsdal has done a great deal of research, tracing titles and production histories back to the early silent days of film-making in Canada. He has dug up many interesting characters and tells their stories with an engaging, witty, conversational tone. The ironies and disappointments of film production in Canada are laid bare: that the first real stab at horror film-making (Julian Roffman’s The Mask [1961]) should have been the work of a successful documentary maker trying to find a little commercial success; that the film Vatnsdal holds up as the quintessential Canuck horror (George Mihalka’s My Bloody Valentine [1982], “the most Canadian horror movie ever made”) was so chopped up by its US distributor that it became almost incoherent.

“I maintain, however, that Canadian horror films – as much because of the pleasurable paradox of the phrase ‘Canadian horror’ as anything – are something much better than run-of-the-mill. Their imperfections often have a gloriously unwitting character, of the sort that makes a subject much more attractive than it would be otherwise: the allure of the underdog, the runt, the deformed cousin living in the attic. They are disparaged, denied or ignored in their own country; they are hatched and just as quickly consigned to a stateless bastardy, wandering the continent looking for an audience and maybe a little respect, and, finding none, they curl up on the bottom shelves of the back rows of the most disreputable video shops in the crummiest quarters of town, or else pop up late at night on one of a dozen theme cable channels.” (12)

This passage illustrates Vatnsdal’s approach perfectly: written with enthusiasm and wit, an energetic embracing of the films he’s dealing with, it nonetheless contains an almost sad admission of the lowliness of the genre, a realization that whatever he might say to help make the films visible won’t actually boost their reputation.

But in telling the stories of the production of this ragged collection of films, Vatnsdal presents a microcosm of Canadian film-making in general. He has written a lively narrative of the struggle against recalcitrant economic circumstances, the indifference of the wider audience to homegrown fare, the persistent effort to create something distinctive and, if possible, original within a market glutted with mediocrity and repetition.

For the fan of horror, though, it is his amusing and enthusiastic descriptions of the films themselves which offer the book’s greatest pleasure. While they often sound pretty dreadful, Vatnsdal manages to pique your interest enough to want to see them – which in the end is the chief, and most valuable, purpose of the book: to instill a recognition that there is life, crippled and distorted though it might be, in Canadian film and to show that we are capable of creating our own entertainments.

Although Vatnsdal doesn’t succeed in his stated aim (identifying and defining a distinctive genre of Canadian horror), he has written a useful and entertaining book about the nature of film-making in Canada, a book which is as much fun to read as (if not more so than) the movies he describes are to watch.

Comments