Flipside: The Black Panther (1977)

Released simultaneously with the Andy Milligan double-bill Nightbirds and The Body Beneath, the BFI Flipside edition of Ian Merrick’s The Black Panther (1977) resurrects an essentially lost British film which suffered a quick death because it took as subject something too raw for British audiences (or at least the British press) to tolerate. Merrick had returned to England after working for several years in New York for exploitation producer-director Barry Mahon, hoping to revitalize the moribund national film industry with an exploitation model that used modest budgets and high profile subjects to generate self-sustaining production. At the suggestion of producing partner Peter Long (brother of the legendary Stanley A. Long), the subject chosen for his initial effort was the recently ended crime spree of one Donald Neilson. In classic exploitation fashion, the film was actually released shortly after the end of Neilson’s trial.

Interestingly, Merrick approached the subject not with an over-heated exploitative fervour, but rather with a coolly detached sense of responsibility. The script by Michael Armstrong (writer and director of Mark of the Devil [1970], one of the best and nastiest movies about medieval witch persecution) adhered scrupulously to the known facts as set down in the court records. As a result, The Black Panther is restrained to the point of under-dramatizing the events, making use of minimal dialogue and no attempt to psychologize the character.

Neilson was an ex-squaddie who, after leaving the forces, fantasized a life as some kind of master criminal. In long wordless stretches Merrick observes him meticulously planning his crimes with an obsessive military precision, each one an assault on a remote village post office accompanied by maps and diagrams of the objective and all possible escape routes. But like many a delusional person, Neilson’s fantasies just wouldn’t play out in the real world. He netted pathetically small sums from his robberies and in anger and frustration ended up killing several postmasters, always returning home to a wife and daughter who quietly submitted to his oppressive authority.

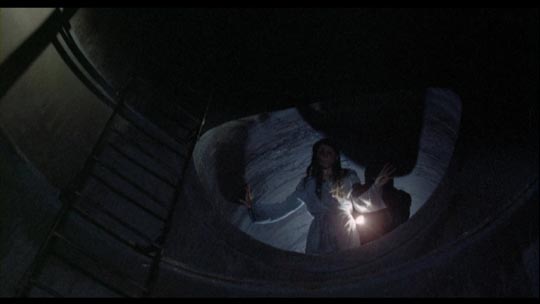

Deciding to aim higher, Neilson finally settled on a plan to kidnap a teenage heiress for ransom. The abduction went smoothly and he imprisoned her in a deep drainage shaft near a pool in an isolated park while he waited for the money. But his plan really wasn’t coherently thought out and small obstacles and misunderstandings kept interfering. Having missed the connection for the ransom drop, he completely lost control and killed the girl. Several months later he was picked up purely by coincidence when, while waiting at a roadside, he mistakenly thought a couple of policemen had spotted him and overreacted by pulling a gun on them.

Despite Neilson’s delusions of grandeur, there was nothing remarkable or even remotely clever about his criminal schemes. He was a petty thug who fumbled every plan and inevitably ended up in custody. But the film achieves a chilling portrait of this aimless villainy, thanks to Armstrong’s spare script, Merrick’s restrained direction, and a genuinely terrifying performance by Donald Sumpter in the lead. An actor with a long and fruitful career in movies and television, he gives a performance here completely stripped of any kind of vanity, immersing himself in this nasty little man with total conviction. This is no larger-than-life villain whom we can vicariously root for, but rather an unthinking brute crashing through life doing nothing but harm.

What makes The Black Panther so chilling is Merrick and Armstrong’s refusal to offer release through melodrama, or editorial commentary … we’re left to figure out for ourselves what might drive such a mundane monster, and to note the discrepancy between his own grandiose self-image as some kind of master criminal and the actual nature of his pathetic and pointless crimes.

As for the film’s failure (Merrick’s ambitious production plans came to nothing, and he only directed one other movie, the poorly received The Sculptress [2000]), it seems that it was partly due to poor timing – the real-life events were still too fresh when the film was released – and partly to the fact that, although only tangentially addressed, it indicted police incompetence and the national press for a kind of complicity in the death of the girl because, the news having leaked out, reporters interfered with the attempts to make the ransom pay-off. Although as a film The Black Panther received some positive reviews, in the press in general it was attacked as an unconscionable attempt to cash in on the tragedy (with the irony of that no doubt lost on the self-righteous editors who launched the attacks).

The BFI disk rescues this forgotten film from obscurity with an excellent transfer, the usual informative booklet, and a short supplemental film, Recluse (1979), about another real-life tragedy, a triple murder-suicide on a remote Devon farm in the mid-’70s. In just half an hour, director Bob Bentley illuminates the tensions among an elderly woman and her two brothers as they struggle with the necessity of finally giving up their unprofitable farm. But while the film was shot on the actual abandoned farm just a couple of years after the events (all that minutely detailed set dressing was actually left there by the dead siblings just as the camera sees it), Bentley takes a much more conventional approach than Merrick, sketching in characters and dramatizing scenes as they might have happened.

Comments