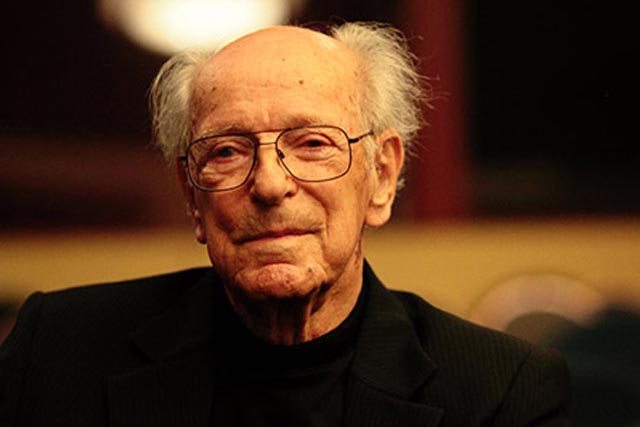

Kurt Maetzig (1911-2012)

I was surprised to read over the weekend of the death of Kurt Maetzig. He was 101.

Maetzig began his career in film in the ’30s with work on film technologies and animation. After the rise of the Nazis his work permit was revoked because of his mother’s Jewish heritage, and he spent the war years as a member of the Communist Party. After the war, he remained in East Germany as a committed socialist, joining DEFA, the state-owned film studio, where he became one of the major figures in the industry. After producing a number of documentaries, he directed his first feature in 1947.

While his career had ups and downs typical of an artist working in the Soviet bloc during the Cold War, he was quite prolific for the next thirty years. But his work was not widely known in the West, apart from his 1960 science fiction movie Der schweigende Stern (The Silent Star), which was released in the States by Crown International in a shorter, dubbed version called First Spaceship On Venus (1962).

That film and two others appeared on DVD a few years ago as part of the DEFA Collection from the University of Massachesetts released by First Run Features. I re-watched all three over the weekend, starting with Der Rat der Gotter (Council of the Gods, 1950), his third feature.

Council of the Gods (1950)

Essentially a docu-drama about the industrial giant I.G. Farben which, among other things, produced Zyklon B, the gas used by the Nazis in their death camps, Council of the Gods offers an early instance of German post-war self-examination which might have been difficult to produce in West Germany at that time, but was facilitated in the East by communist propaganda aims. The film centres on Dr. Hans Scholtz (Fritz Tillmann), a research chemist whose work on various projects results in a toxic compound which, unknown to him, is transformed into the deadly gas by another department.

Meanwhile, the head of the company, Chairman Mauch (Paul Bildt), makes deals with Mr. Lawson of Standard Oil (Willy A. Kleinau), a sinister representative of American capitalism, which will ensure the uninterrupted flow of money and resources no matter what happens during the war – including the assurance that the Farben plants won’t be bombed.

Scholtz is increasingly disturbed by the social transformations around him, including his own son’s induction into the Hitler Jugend. When he finally discovers what his work has been used for, he’s appalled and after the war, at the I.G. Farben Nuremberg trial, he alone acknowledges a sense of guilt as everyone else, up to the Chairman himself, tries to squirm out of any responsibility. In fact, the prosecutors even collude with the defendants in order to conceal U.S. complicity in the company’s crimes and Scholtz is dismissed as a madman.

Aside from the propaganda overlay, Council of the Gods is a powerful look at what life was like inside Nazi Germany and the ways in which people accommodated themselves to the Party’s increasing derangement of society.

The Silent Star (1960)

The Silent Star (1960) is far less successful. Adapted from The Astronauts, a novel by Stanislaw Lem, it also is larded with propaganda as it tells of the discovery of an alien artifact which is apparently a remnant of a spaceship which caused the great Tunguska explosion in Siberia in 1908. A multinational team sets out to decode the message recorded in the device, managing to deduce that it came from Venus. Efforts to contact our sister planet bring no results, so the recently completed Mars rocket is rerouted to go looking for whoever sent the message.

In many ways, The Silent Star resembles the American space films of the ’50s (Destination Moon [1950], Rocketship X-M [1950], Conquest of Space [1955]); it’s a mission film, with a group of intrepid specialists flying into the unknown … or rather not-so-unknown, as they go through a checklist of experiences which include weightlessness, a space-walk to fix some damage, a dangerous cloud of meteors, and unappetizing food concentrates. All of this is handled in a very perfunctory way as a couple of the scientists continue their attempts to decipher the alien message.

Not surprisingly, it turns out to be something other than “hello”; when the crew arrive on Venus they find out that the Tunguska crash was the vanguard of an invasion, but luckily for us, the Venusians’ giant energy weapon which was pointed at Earth malfunctioned and they destroyed themselves instead. After the required sacrifice of a few lives in order to save the ship, the surviving crew return to Earth with a warning that we’d better stop building bigger and better weapons …

The most interesting thing about The Silent Star is the aggressively international composition of the crew, with scientists and technicians of every colour, from every continent, indicating a unified future … well, unified except for the still-paranoid Americans. The American on board, Professor Harringway Hawling (Oldrich Lukes), joined the team against the angry opposition of his colleagues back home who distrusted the mission.

The real problem with the film is that Maetzig obviously had no affinity for the genre. Despite the gaudy design and some interesting details like the advanced (for the time) robots, Maetzig’s staging is flat and unimaginative and the movie plods through its story points with no sense of engagement.

The Rabbit Is Me (1965)

It’s hard to believe that Das Kaninchen bin Ich (The Rabbit Is Me, 1965) could have been made by the same director. In the early ’60s, under Kruschev, there was an easing up of control in the Communist bloc and for a brief time it seemed that artists and writers could be more honest about life behind the Iron Curtain. It was during this short-lived thaw that Maetzig somehow managed to get approval to adapt a novel by Manfred Bieler which had not been officially published. The story, about a girl whose brother is convicted of sedition in a closed trial and sentenced to three years in prison, reveals the hypocrisy of the judicial system through an emotionally and psychologically nuanced character study.

The girl, Maria Morzeck (Angelika Waller), in trying to apply for a pardon for her brother, finds herself slipping into an affair with Paul Deister (Alfred Muller), the judge who convicted him. Conflicting political aims are complicated by a genuine emotional connection, and the film delineates the ways in which human relationships are distorted by the pressures of an oppressive system. But the heart of the film is the richly drawn narrative of Maria’s growth from naive girl to strong self-willed woman.

After the stodginess of The Silent Star, the nouvelle vague-influenced stylistic play of The Rabbit Is Me is a revelation; you can almost feel the relief Maetzig experienced once he was free of the requirements of state-ordained propaganda. The sense of creative freedom combined with the charm of the actors makes the film feel completely undated.

Naturally, it was banned along with a dozen other films by the cultural authorities when Kruschev was replaced by the reactionary Brezhnev, and Maetzig, a deeply committed believer in democratic socialism, was condemned not only for the film’s criticism of the state, but also for its uninhibited portrayal of sexuality. It finally saw the light of day only after the collapse of communism in 1990.

Kurt Maetzig retired from directing in 1976. He died on August 8.

*

Just as I was finishing this piece, I stumbled on the news that Chris Marker has also died – on July 29. Not sure how I missed that. This remarkable cine-essayist made two of my all-time favourite films: La Jetee (1962), the single greatest science fiction film, and Sans Soleil (1983), an endlessly rewarding meditation on time, memory, and our relationship to place.

Comments

I found this exceptionally well written.