Whatever Happened to Jim McBride?

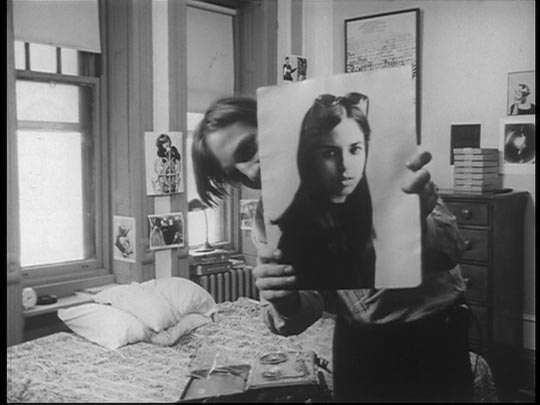

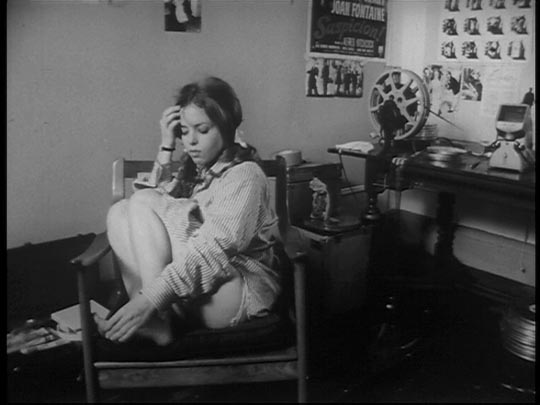

Jim McBride was one of the most interesting and accomplished filmmakers to emerge in New York City in the ’60s, debuting with the remarkably assured and inventive David Holzman’s Diary in 1967. One of the earliest, and finest, examples of faux documentary, it fooled many people with its convincing portrayal of a filmmaker (L.M. Kit Carson) creating a self-portrait/diary about his life in an attempt to find some core of meaning in his existence. There’s an authenticity to the film which makes it a strikingly evocative document about a specific time and place, with its beautifully shot (by Michael Wadleigh – on-screen: Michael Wadley) images of the streets, parks and people of David Holzman’s neighbourhood.

What at first seems invisible is the razor-sharp satire of the self-absorbed “artist” disappearing into his own pretension, driving everyone – friends, girlfriend – away with his obsessive need to incorporate them into his own “story”. As the film develops, the viewer gradually shifts from sharing Holzman’s fascination with his own life and surroundings to an increasing irritation with what emerges as a kind of blindness facilitated by the equipment he unconsciously uses to create a barrier between himself and everyone around him.

McBride followed David Holzman up with an actual documentary, My Girlfriend’s Wedding (1969, also shot by Michael Wadleigh [Wadley]), in which he turns the camera on his own life and the strange circumstance which requires his English girlfriend (Clarissa Ainsley) to marry an American in order to stay in the country. The film itself never addresses why she can’t just marry McBride, focusing more on her in extended monologues in which she reveals details of her life – almost like a mirror image of Holzman’s girlfriend’s reluctance to appear on camera (McBride always wanted the two films to be screened together as a kind of diptych). (In an interview on Second Run’s Region 2 edition of Holzman and Girlfriend, McBride explains that Clarissa had already arranged to marry a Yippie whom she hadn’t met, and that he himself had not yet divorced his own wife.)

She talks of her relationship with her father, of a son who is not living with her, of a second child she gave up for adoption, of a recent abortion … coming across as engaging and attractive even as her life is revealed as troubled, underlining the strangeness of the impending wedding to a man she’s known for only a few weeks.

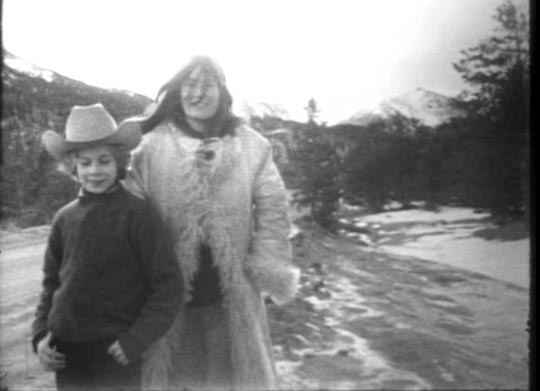

Two years later, McBride made a kind of sequel, Pictures From Life’s Other Side (1971), in which he, Clarissa (the “girlfriend” of the previous film) and Clarissa’s son, Joe, set out to drive across country to San Francisco. This film perhaps reflects its time even more sharply than the earlier films, its casual attitude towards sexuality and nudity almost impossible to conceive in a film made today. Much of it was shot (by McBride and Joe) in motel rooms where all three are frequently naked, where sex between McBride and the pregnant Clarissa is not hidden from the boy. What may have seemed liberating in 1971, now inevitably causes a certain degree of discomfort.

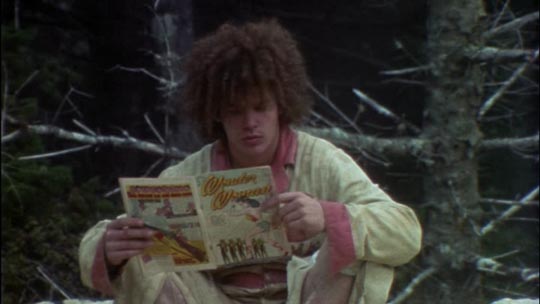

That same year, McBride made his finest film, Glen and Randa (1971), a post-apocalyptic story about a young couple wandering through a wasteland in some undetermined future. McBride uses the same loose verite techniques as the earlier films, resulting in one of the most convincing visions of the collapse of civilization ever put on screen. The wandering population of this world are a hopeless, traumatized lot, blank and aimless. Glen (Steven Curry) and Randa (Shelley Plimpton), born into this world, have no grounding in culture, history, community, but after Glen glimpses a “city” in an old Wonder Woman comic book, a place full of people who can fly, he decides he wants more and sets out with Randa tagging along although she shows no particular interest in his quest.

His follow-up to Glen and Randa, Hot Times (1974), an attempt to dissect sexuality as presented in the media, was compromised by distributor interference and censorship. He didn’t direct another film until his disastrous act of hubris in remaking Breathless in 1983. This attempt to update and transpose Godard’s debut feature – a film which was predicated on an obsession with the impact of American popular culture on Europe – to an American setting was a creative and commercial failure. Although McBride fared a bit better critically and commercially with his neo-noir The Big Easy (1986) and the Jerry Lee Lewis bio-pic Great Balls of Fire! (1989), he seems to have done little of distinction since.

What seems clear in re-watching the early films (collected on Lorber Films’ Blu-ray edition of David Holzman and the documentaries, and VCI’s rather murky 2009 edition of Glen and Randa), is that McBride was intensely engaged with a particular time and place, his work rooted in the upheavals and questioning of the ’60s. His subsequent career suggests that he was less inclined to adapt to the social and artistic changes that occurred during the mid-’70s and the eventual hegemony of the mainstream commercial model of filmmaking that more or less erased the more experimental options which briefly flowered in the late ’60s and early ’70s.

I do recall, while on a visit to friends in Los Angeles in 1983, reading a script that McBride had written. Tom Mix and Pancho Villa was based on Clifford Irving’s novel about the silent-movie western star getting involved in the Mexican revolution, and on the page it was an impressive and exciting piece of work, but it was never produced (though the New York Times indicates that at some point Tony Scott was going to do something with it). If he had found the backing, this might have been the film to re-establish McBride … but of course that’s pointless speculation. The early films still stand as works of real stature, well worth revisiting, regardless of what happened later in his career.

It’s a pity that Lorber’s disk doesn’t provide any supplements to illuminate the origins of those early films (you have to go to Second Run’s David Holzman DVD for that), while the VCI disk does contain a frustrating interview conducted by someone who seems to know nothing about the director and his work; as it goes on you feel increasingly embarrassed for McBride, who remains polite in the face of this ignorance but ultimately ends up revealing little about himself and his films.

Comments

Is there any known contact info for Jim McBride? Email, Facebook, Twitter?

Sorry, I don’t have any information about his current whereabouts.

My email is jmcb41@gmail.com. I had nothing to do with the Tom Mix script, and I’m quite proud of Breathless, The Big Easy, and Great Balls of Fire!

My mistake, I guess. I was sure that when I was given a copy of the Tom Mix script in December 1983 your name was attached to it …

And I meant no disrespect, although I guess my comments on Breathless are kind of harsh!

David Holzman, Glen and Randa and the documentaries remain among my favourite films …