DVD Review: Laddaland (2011)

Laddaland (2011) is a recent Thai entry in the Asian ghost genre. Interestingly, it also seems to draw on a western strain of horror, what you might call “real-estate anxiety” as exemplified by Poltergeist, The Amityville Horror, even to some degree the Paranormal Activity series. Here the fear is rooted more in economic and status related issues than the ghosts that come to seem like a projection of financial insecurity. The core of this mini-genre is the middle class family which finally attains the dream home they’ve longed for only to find that it doesn’t offer the security and safe haven they expected.

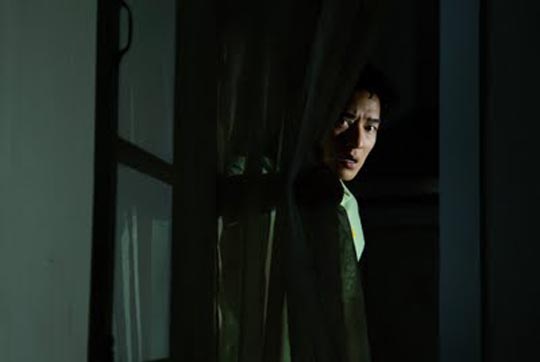

In Laddaland, co-written and directed by Sophon Sakdaphisit, the family is fractured, with father and husband Thee (Saharat Sangkapreecha) struggling to make a living as a salesman. He has recently made a down payment on a house in a gated subdivision (the Laddaland of the title) in Chiang Mai in order to provide a solid base for his wife Parn (Piyathida Woramuksik) and two children, teenager Nan (Suthatta Udomsilp) and younger son Nat (Apinya Sakuljaroensuk). The girl is rebellious and resentful at being dragged from her grandmother’s home and her friends in Bangkok; Thee’s defensiveness shows in anger towards her and a seeming preference for his son. Parn is caught between her wealthy mother who is openly hostile to Thee as unworthy of her and her husband whose insecurity constantly manifests in ways which undermine his intentions for the family.

Things are further complicated by the neighbours, a businessman, his wife and young son, and a wheelchair-bound mother. A minor incident with a cat which poops on Thee’s driveway exposes a disturbing undertone of violence in the house next door, where we start to see various bruises on the wife’s face, see the father hit the son, and eventually hear angry arguments escalating into physical violence. These neighbours serve as a visceral warning of where Thee’s family may well be heading, and there’s a solid story in this situation.

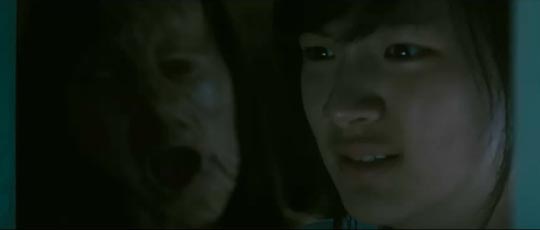

But then Sakdaphisit introduces the ghost. Thee mentions to Parn that he has hired a Burmese maid who works at a nearby house to come in occasionally. The first time we see her, there’s something odd: she stands with her back to the road aiming a water hose at a flowerbed, but ignores Thee when he tries to talk to her, eventually walking away around the house. Not long after, a television news report reveals that the woman had been brutally murdered and stuffed inside a refrigerator inside the house days earlier. In traditional genre fashion, Thee doesn’t put two and two together, and fiercely maintains long past all reason that there is no ghost in the community … but of course, given all his problems, he has no choice. The house means everything to him, his whole identity being tied up in providing this home for his family.

But the longer he clings to that dream, the more he inadvertently contributes to the family’s disintegration. After Nan encounters the ghost, he calls her a liar and physically drags her back into the haunted house, ignoring her absolute terror and driving her even further from him.

As the family struggle to get through their personal issues (including Thee losing his sales job and being forced to become a retail clerk), in the background we see the gated community gradually emptying out and taking on a desolate, abandoned look – everyone else is trying to get away from the ghost (actually ghosts, as other acts of violence increase the spectral population), Thee alone clinging to the dream of property and privilege.

None of this is likely to end well, and indeed it does finally go pretty much where you’ve expected it to go. And that is ultimately the film’s biggest weakness.

When Asian horror began to turn up in the west in the late ’90s (Hideo Nakata’s Ringu being the big breakthrough in 1998), its impact was largely due to cultural differences and the narrative expectations that derived from them. These movies were seriously unsettling because they didn’t adhere to what western viewers had become accustomed to as “the rules” of storytelling. Deeply mysterious, rooted in an attitude to the supernatural which defied western rationalism, they were imbued with an atmosphere far creepier than we were used to in the graphic physical violence that has characterized most western horror for some time now.

It’s instructive to note the differences between the Japanese Ringu and the American remake, The Ring (2002); the latter tries to replicate the scares of the original, but at the same time it works mightily to impose sense on the narrative, to turn the dreamlike disturbance of Nakata’s film into a logical story with clearly delineated motivations, to explain. As a result, for all its technical accomplishments, it fails to get under the skin and leave the viewer with the lasting unease of the original.

The evolution of the genre can be seen clearly in the progression of Takashi Shimizu’s Ju-On/Grudge series. The original V-horror film and its sequel (both 2000) were and remain two of the scariest films ever made; when he remade them as theatrical features (2002, 2003), with bigger budgets and more technical resources, they offered diminishing returns because he was now merely reiterating effects which had already been seen; then when he again re-made them as the American Grudge (2004) and Grudge 2 (2006), there was no longer anything fresh about his ghost effects and they merely resembled the Americanized Ring films.

By the time we get to Laddaland, the tropes of Asian horror no longer have the unexpectedness which made the earlier films so effective. While Sakdaphisit is effective at the domestic drama and the psychological stresses working to destroy this family, his ghost story is full of rote moments and predictable effects – every manifestation is structured in such a way that you know exactly when and where the phantom will appear in the frame, and he delivers exactly what you’ve expected so there’s no kick to the shock. It all seems rather tired and mechanical and in the end undermines the effective work of the actors to create believable characters and a realistic family.

Far scarier than the ghosts is the moment when Thee arrives at the office to find it locked and his company shut down, owing him back pay which he desperately needs to pay the mortgage, and the later moment when he turns to serve a customer at the convenience store and finds himself face to face with Nan, who increases the awkwardness of the moment by telling him to “keep the change”.

Birch Tree Entertainment’s DVD edition of Laddaland offers a slick visual presentation of the digitally shot film, defaulting to the English dub when you hit play. There are a couple of brief EPK featurettes of interview clips with the director and actors and a trailer which promises more horror than the feature actually supplies.

Comments