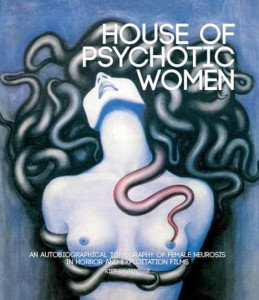

Book Review: House of Psychotic Women by Kier-La Janisse

Kier-la Janisse has had a varied and colourful career as a film and music programmer in various places, including Vancouver, Austin TX, Winnipeg and Montreal; she initiated and ran a festival of horror and fantasy films in Vancouver called CineMuerte and has connections with Montreal’s Fantasia Film Festival. Her first book, a slim, attractively designed pocket-sized ode to Italian genre bit-player Luciano Rossi, A Violent Professional (FAB Press, 2007), was the engaging work of a devoted fan (she rates each entry with one to four stars for the quality of the movie, and one to four hearts for Rossi’s presence). Her second book, just released by FAB Press, is something very different. House of Psychotic Women is a remarkable, disturbing work and quite unlike anything else I’ve ever come across, what might be called autobiographical film criticism, or even self-therapy through movies.

Addressing her life-long attraction to horror and exploitation films, Janisse digs deep into her own past to understand not only the content of these films, but also the ways in which they illuminate her own experience; her forthright account of childhood abuse and the ways in which it shaped her own behaviour and choices in later life is as disturbing as the content of any of the movies she analyzes with incisive clarity. But what makes the book unique is the ways in which the content of her life and the content of the films are woven together to reveal just how and why we watch movies and why and how we tend to choose the movies that we do watch.

I personally gave up on film theory after immersing myself in it for several years in the ’80s because I came to realize that all the elaborate social, psychological, and ideological edifices erected by competing academics ultimately said nothing about the personal, visceral experience of sitting in the dark and watching. There’s an intensely subjective aspect to film-viewing, and every film consists not only of what the filmmaker has put up on the screen but also what we, as individual viewers, bring into the dark with us. This is why there’s seldom any critical unanimity about any particular film, and why we’ve all had the experience of being moved, even deeply affected by a movie we know on a superficial intellectual level isn’t “a good film” in any artistic or aesthetic sense.

Janisse herself feels a deep connection with horror films, apparently dating back to an early childhood television encounter with Eugenio Martin’s Horror Express (Panico en el Transiberiano, 1972) – “my first fully-formed cognitive memory”. The priest on the train (Alberto de Mendoza), possessed by an alien force which makes his eyes glow as he sucks the life force out of his fellow passengers, became her personal boogeyman, appearing in her dreams for years afterwards — the frequent repetition producing a gradual transition from fear to curiosity.

Throughout the book, Janisse pursues this curiosity as she examines her own life, both the external factors – adoption, abusive step-parent, problems socializing and relating to other kids at school, in fact the classic acting out of the juvenile delinquent – and her own inner responses, delineating the formation of her own personality and ways (which always seemed insecure and even hostile) of interacting with the world. She found reflections of her own circumstances in the movies that attracted her, and through the process of interpreting those movies began to form a clearer understanding of her own personality and the difficulties she experienced in relating to other people. That process forms the substance of House of Psychotic Women, which is subtitled An Autobiographical Topography of Female Neurosis In Horror and Exploitation Films.

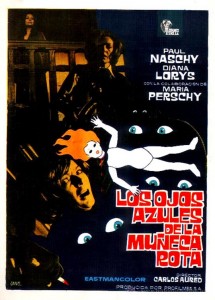

The majority of films treated in the book are what might be considered disreputable by the mainstream – a particular attraction to Italian thrillers (gialli), most of which involve twisted sexuality and psychotic killers; rape-revenge films which paradoxically deal simultaneously with female dis-empowerment and consequent anti-social forms of empowerment – but the common thread is always the woman’s psychological response to social and personal situations which force a derangement of self-perception, movies as wide-ranging as Anatol Litvak’s The Snake Pit (1948), in which Olivia De Havilland plays a middle-class woman who finds herself in an insane asylum; Antonioni’s Red Desert (1964), in which Monica Vitti plays one of modern cinema’s key representatives of alienation; Ken Russell’s devastating depiction of religious and sexual madness, The Devils (1971); and numerous Euro-sleaze titles in which bourgeois women find their connection to reality disintegrating.

As the book unfolds, Janisse’s personal story at times overwhelms the movies and a kind of tension develops between the function of film criticism and the needs of the confessional memoir. Typically, a critic, no matter how passionately committed, takes a position somewhat outside of the object of their interest and the reader joins in that intellectual process. Janisse’s approach, immersed in her subject at the deepest emotional and psychological level, at times unbalances the reader – there are some points in the book when the reader might feel they’re getting “too much information”, an almost claustrophobic sense of being enveloped by the author – which is analogous to being enveloped as a viewer by the on-screen madness she’s writing about.

In a way, this produces a mirror image (and mirror images are vitally important to many of the movies she discusses) of the abstract intellectual film criticism I previously mentioned; because of her concern with the psychological content of the films and her personal relation to them, she largely avoids offering specific critical evaluations or passing aesthetic judgement on them. In a sense, the “quality” of the movies is irrelevant to the process she’s describing … which brings us back to the point that our relationship to movies (as to all art) functions on a deeper, more irrational level than that of technical and aesthetic standards.

But that said, perhaps the book’s one real weakness is the missed opportunity to provide more objective commentary in the lengthy filmography which occupies the second half. Here Janisse provides short comments (from a single paragraph to a full page) on every movie mentioned in the main text as well as many others which share similar thematic concerns. For the ones already mentioned, she merely restates what she’s already said, and for the newly introduced titles she offers brief plot summaries and a few comments about their thematic relationship to the book’s thesis, rather than expanding consideration of the movies in question beyond that very personal connection with her own life experience. Nonetheless, the filmography still serves as a useful guide to anyone who wants to explore this particular corner of the cinematic universe, and it certainly takes nothing away from the strengths and interest of the main text.

House of Psychotic Women is a strange, perhaps unique, work of film criticism. Kier-La Janisse finds in her chosen films about female neurosis and psychosis a mirror in which she can more clearly see her own experience, and understand not only her own troubled behaviour as a child, teen, and even adult, but also the actions of her mother, her siblings, her abusive stepfather and the people she has chosen to be with as an adult.

By delving so deeply into her own “case history”, Janisse shows that our relationship to the movies is not one of detached observation; it’s symbiotic. We project ourselves into the screen where our past histories mingle with the narrative fiction, transforming it through our own memories, desires and expectations as it in turn transforms us, sometimes superficially just for the moment of viewing, but sometimes far more deeply and with long-lasting effects.

Comments