Recent Viewing 1

It looks like I haven’t reported on my home viewing in quite a while, so looking back over my notes, there are far too many titles to comment on in detail. Some of these are films I’ve looked at again because of recent Blu-ray releases – the Alien series, for instance, and the Red Riding Trilogy, Jean Renoir’s Swamp Water, and the 1990s Gamera trilogy, Leone’s Dollars trilogy, Nick Park’s Wallace and Grommit shorts, Henry Levin’s Journey to the Centre of the Earth, Peter Newbrook’s The Asphyx, Jean Rollin’s Le Viol du Vampire, Requiem pour un Vampire, Les Demoniaques, Les Deux Orphelines Vampires and La Morte Vivante (the first Rollin movie I ever saw and still one of my favourites – in fact, it was the first DVD I ever bought), Richard Brooks’ Bite the Bullet …

In most of these cases, my opinion about a film hasn’t changed as a result of the HD upgrade. I still like the second and third Alien instalments more than the first and fourth, though I was surprised to realize just how much Alien Resurrection was Joss Whedon’s trial run for Firefly/Serenity, his style combining with director Jean-Pierre Jeunet’s sensibilities to create something which really doesn’t seem to belong to the Alien universe.

A second viewing of the three Red Riding (2009) films proved less impressive than the first; the darkness of the series is so over-emphatic that it eventually becomes ludicrous rather than tragic. With every member of the West Yorkshire police department, not to mention businessmen, clergy and just about everyone else in sight, presented as paedophiles, perverts and murderers who commit their heinous crimes for decades with impunity, there’s little room for any kind of genuine moral conflict.

Richard Woolley’s Brothers and Sisters (1980)

As an interesting contrast, I also watched Richard Woolley’s Brothers and Sisters (1980), a somewhat didactic treatment of the impact of the Yorkshire Ripper case (central to Red Riding) on a group of people who span the social and political spectrum of ’70s Britain. I first saw this movie at the Hong Kong Film Festival in 1981 and it still packs a punch. Woolley, in his first 35mm feature, retains his political and structuralist concerns while aiming deliberately at a more accessible narrative. The brothers are left-wing activist David Barratt (Sam Dale) and James Barratt (Robert East), a middle-class army officer. David is disgusted by his own roots in the wealthy middle class and can’t avoid creating confrontational scenes when he returns to the family estate for weekend visits.

While on those visits, David is involved in a casual sexual relationship with his brother’s kids’ nanny (Carolyn Pickles), something he keeps secret from the woman he has a relationship with at the socialist/feminist commune he lives in back in the city. The narrative, which shifts back and forth in time, requiring focused concentration to keep the storyline straight, revolves around the murder of the nanny’s sister, a prostitute (Pickles again) who becomes the victim of a Ripper-like killer. As all the characters are drawn into the police investigation, Woolley dissects their beliefs and attitudes; although the mystery remains unresolved, the film is littered with signs which at different times implicate both of the brothers. (In the interview with Woolley which accompanies the feature, he recounts an amusing incident in which an American viewer explained to him that it was the woman from the commune who killed the prostitute, acting out her own issues arising from David’s infidelity.)

Although there’s a definite schematic quality to the film, supporting its agenda of exploring gender attitudes, it’s far more nuanced and convincing than the overwrought Red Riding Trilogy.

Ken Burns’ Prohibition (2011)

Very different social attitudes are dissected by Ken Burns in his excellent three-part documentary Prohibition (2011). I must confess that I haven’t seen much of Burns’ work. I couldn’t get through The Civil War because it seemed to be a shapeless collection of incidents and characters which had no clear historical line to give it structure; I constantly felt that I ought to have more than a passing knowledge of the period in order to make sense of the series. Prohibition, on the other hand, is a model of clarity, tracing the fraught relationship between evolving 19th Century American society and the demon liquor. The roots of prohibition lay in a complex mix of social, religious and ethnic factors which fought with one another to define what it was to be American.

Having laid out this background, Burns presents a lively account of the impact of a law which, in effect, criminalized the majority of the population. Good intentions ended up instilling a powerful and indelible contempt for the idea of government and the law which paradoxically resulted in the valorization of flamboyant and successful criminals, and established a powerful culture of organized crime which still exists in the States.

Jacques Deray’s Borsalino and Co. (1974)

A friend recently gave me a copy of Jacques Deray’s Borsalino and Co (1974), a sequel to his own Borsalino (1970). I haven’t seen the original, which has Jean-Paul Belmondo and Alain Delon as partners in crime in 1930s Marseilles. In fact, I don’t think I’ve seen anything by Deray before. Starting with the funeral of the Belmondo character, this sequel pits the charismatic Delon against a right-wing faction from the north which is intent on taking control of all crime in the city in preparation for the coming triumph of fascism. Thus the gangster Roch Siffredi (Delon) becomes a heroic figure, presaging the resistance to the collaborating establishment in Occupied France just a few years in the future.

Colourful design and a good cast, with plentiful fairly graphic violence, reflect an interest in the American gangster film similar to Jean-Pierre Melville’s, but (judging by this one film) Deray is a more conventional filmmaker than Melville, so Borsalino and Co never achieves the mythic dimension of films like Bob le Flambeur, Le Deuxieme Souffle or Le Samourai.

Nicholas Ray’s King of Kings (1961)

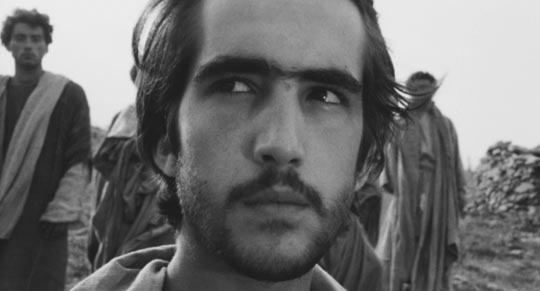

& Pier Paolo Pasolini’s The Gospel According to Matthew (1964)

Since I have no particular religious convictions, I respond to Biblical movies as movies, rather than judging them for their faithfulness to the “original text”. The Bible, of course, has been a source for vast quantities of Hollywood kitsch – Cecil B. DeMille was the king of this kind of trash epic, peaking with his final movie, The Ten Commandments (1956). But many major filmmakers tried their hand at the genre – John Huston with The Bible: In the Beginning … (1966), William Wyler with Ben-Hur (1959), Richard Fleischer with Barabbas (1961), Henry Koster with The Robe (1953) , George Stevens with The Greatest Story Ever Told (1965) … But perhaps one of the oddest things in this trend is finding the name of Nicholas Ray – a master of psychological storytelling – on King of Kings (1961).

King of Kings was the first of four big-budget epics produced by Samuel Bronston in Franco’s Spain (followed by El Cid [1961, directed by Anthony Mann], 55 Days At Peking [1963, also partially directed by Ray], and The Fall of the Roman Empire [1964, Anthony Mann again]). Bronston’s productions were characterized by no-expense-spared production design, big casts of stars, and a general tension between massive scale and an attempt to humanize history.

King of Kings has been much criticized for the casting Jeffrey Hunter as a blue-eyed Jesus, but the actor acquits himself quite well, managing to hold his own against the cast of thousands background as Philip Yordan’s script takes the character through the familiar story while making an effort to depict the social and political details of the time. That effort is actually another prime source for criticism of the film; Jesus is less foregrounded than usual. In fact the script doesn’t bother with many of the most famous incidents which usually mark the story (the wedding at Cana, raising Lazarus from the dead, etc), while his story is paralleled with that of Barabbas (Harry Guardino), here a revolutionary looking for a way to overthrow the Roman occupation, the sword to Jesus’ staff.

While much of this narrative may have been invented by Yordan, it does have the advantage of clarifying the politics surrounding Jesus’ rising influence and what causes the various players to decide to destroy him. Most interestingly, Yordan’s narrative gives clear psychological motivation for Judas’ betrayal. Judas (Rip Torn) is one of Barabbas’ revolutionaries who becomes influenced by Jesus’ teachings; he joins the disciples partly as a link to the revolutionary underground, hoping to harness Jesus’ influence to the cause. When overt revolt fails, Judas decides to turn Jesus in, believing that once he is placed in a dangerous position, he will reveal his awesome powers and smite the enemy. It’s only when he sees Jesus submit to his fate that he realizes how he has misunderstood the teachings and, driven by guilt, hangs himself.

Ray directs the epic with a modest style, telling the story cleanly and simply – which is no small feat when handling scenes with hundreds, even thousands of extras. Although the film ends with the usual resurrection, it’s surprisingly free of the sanctimony that often characterizes Hollywood religious epics.

Pier Paolo Pasolini’s Gospel According To Matthew (recently released on Blu-Ray by Masters of Cinema) is about as far as you can get from Hollywood’s treatment of the story. A Marxist homosexual, Pasolini took the text of Matthew’s gospel as his script, the narrative and dialogue drawn from the original and unembellished with extraneous storylines. He approached it with the documentary eye of an ethnographer, using non-actors and locations (in Morocco and Italy) which have an authenticity rare in religious epics. The story, of course, is familiar; what’s new is the attitude towards Jesus; treated with respect, he’s shown as a radical revolutionary whose teachings threatened the interests of both the Roman occupiers and the native Judean establishment. Pasolini’s purpose was to show that Jesus and his teachings were entirely relevant to the struggle of the modern Left against entrenched capitalism. But he kept that purpose in the background, letting Jesus make the argument for him.

In keeping with that revolutionary purpose, Pasolini’s Jesus is perhaps the harshest ever depicted on film, a rather grimly driven man whose arguments are intended to change life here on earth rather than to promise something better in the great beyond.

There’s a plausible realism to Gospel According To Matthew, but I have to admit that Ray’s King of Kings is the more engaging movie.

Comments