Stanley Kubrick 8A: Male Anxiety and War

– Full Metal Jacket (1986)

It was seven years after The Shining before Stanley Kubrick released his next film. Even given that Full Metal Jacket was two years in the making, that still leaves a long gap, perhaps indicating the difficulty he had in both finding the right subject and securing financing, even though the King adaptation had been reasonably successful after the commercial disappointment of Barry Lyndon.

As producer Jan Harlan says in a documentary on the Blu-ray disk, Kubrick had wanted to make some kind of definitive statement about war – a subject which ranks high in his work (Fear and Desire [1953], Paths of Glory [1957], Spartacus [1960], Dr. Strangelove [1964], Barry Lyndon [1975]) – but not necessarily about Vietnam. The director started work on adapting Gustav Hasford’s novel The Short-Timers after the first big wave of Vietnam movies … Ted Post’s Go Tell the Spartans, Hal Ashby’s Coming Home, Michael Cimino’s The Deer Hunter (all 1978) and Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now (1979). Kubrick’s film came in the second wave, marked more (to varying degrees) by an attempt at realistic reassessment than myth-making: Oliver Stone’s Platoon (1986), John Irvin’s Hamburger Hill (1987), Brian De Palma’s Casualties of War (1989).

Kubrick being Kubrick, his film is unlike any of these others in both tone and theme. Not surprisingly, he approached Vietnam with a mixture of deadly seriousness and savage black comedy. Although the film is full of specific references to the conflict and the conflicted attitudes towards it that existed in the late ’60s, his bigger theme is the process of turning a bunch of ordinary young guys into the killers a government needs in order to wage war.

Full Metal Jacket (1986)

Kubrick’s film is divided into two distinct parts, something which has occasionally been criticized as somehow structurally broken. And yet it’s crucial to his purposes. The first section, a classic boot camp narrative, depicts the process of remaking ordinary young men into soldiers; the second section, in Vietnam during the Tet Offensive in early 1968, deals with the consequences of that process. The film is presented as an argument in cause and effect, built around (once again) the awful things that human beings do to each other.

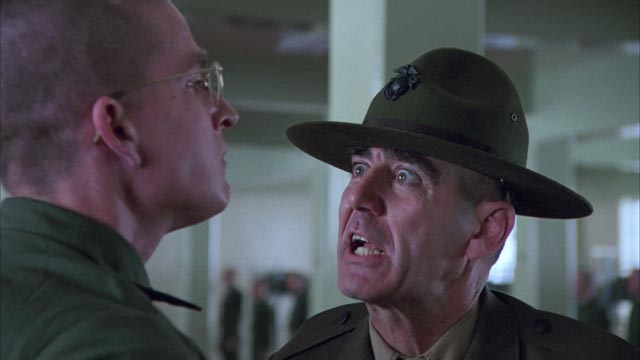

The impression that there is something broken about the structure may be exacerbated by the fact that Kubrick uses two different visual and narrative styles to get his points across. In boot camp, he largely uses an almost rigidly formal approach, best exemplified by the camera movement and cutting in the barrack room scenes with Gunnery Sergeant Hartman (R. Lee Ermey) stalking between rows of recruits standing stiffly at attention, pouring streams of verbal abuse over them. The camera tracks back along the actor’s axis of movement, facing him dead on (usually a violation of the classical rule about “not looking into the camera”), emphasizing the sergeant’s complete control of the dramatic space and absolute power over the recruits. Throughout the boot camp section, we get this sense of relentless movement, never stopping long enough for the recruits to pause for self-examination: they have no choice but to go where they’re being driven by this military force which will absolutely transform them from “girls” into “men”. Scenes are repeated, visually almost identical, emphasizing the conditioning process which is gradually stripping the recruits of their individual identities.

In the film’s second half, the camera no longer controls the space, instead being driven by events; more ragged, more obviously hand-held, more contingent on a reality which is chaotic and in which the only real sense of agency the characters have is aiming and firing a weapon, something which is done spontaneously and frequently pointlessly as there are no visible targets. The pattern of repetition is replaced with randomness and unpredictability, scenes seemingly disconnected from one another.

But consistently throughout the film, Kubrick’s approach is similar to the one he used in Dr. Strangelove. There is a combination of obsessive attention to realistic detail with an at times almost cartoonish exaggeration of character. Gunnery Sergeant Hartman is the essence of the drill instructor, a distillation of every such character who has ever appeared in film before; and yet, he is absolutely authentic – Ermey, a retired officer himself, came up with much of his bile-filled dialogue from his own experience. Hired to whip the actors into shape and to offer technical advice, he took on the role during pre-production, bringing so much authenticity to what may have been a more conventionally written part that Kubrick had no choice but to replace the actor originally cast as Hartman.

The boot camp section focuses on two main characters, Private Joker (Matthew Modine) and Private Gomer Pyle (Vincent D’Onofrio). Joker, true to the nickname imposed on him by Hartman – the sergeant renames every recruit as the first stage of obliterating their civilian identities, giving each of them a generic label based on some prominent characteristic – faces life with a degree of detachment which shows in sarcasm and humour. Private Pyle is a dim-witted country boy who seems constantly to be just short of awareness, staring with the kind of uncomprehending grin often seen on a boy used to being laughed at and bullied. These are the two poles through which we see the effects of basic training.

Hartman ruthlessly targets the vulnerable, overweight Pyle; the boy has no real hope of achieving the hardness which is the aim of the training, so the sergeant uses him as a device to instill that hardness in the others. Pyle is scapegoated, his failures resulting in punishment of the others until they cohere into a single-minded group united in their hatred of him. This process climaxes in a vicious beating in which every member of the squad inflicts pain on the whimpering Pyle, ending with Joker himself who has held back out of a sense of empathy; pushed, he can only overcome his own reluctance and distaste by becoming more savage than the others. And yet his self-awareness causes Joker to feel guilt for what he’s done, still not entirely a part of the group. This outsider position is reinforced when, on graduation, each man is given his assignment and Joker finds himself a journalist for Stars & Stripes rather than a combat soldier, an observer rather than a participant.

The destructive use of gender and sexuality

What is most distinctive about the training process is the use of sexuality and the instilling of fear about the recruits’ sexual identity. They start as “girls”, as “ladies”, with Hartman heaping contempt on their weakness, clearly identified as feminine. The chants they use as they march are sexually inflected, telling them that they must dominate women who are less than they are. Their weapons are identified with their penises, but also the focus of a kind of romantic desire – Hartman has each of them give their M16 a girl’s name and insists that they sleep with the rifle.

In Kubrick’s previous films there is a frequent uneasy subtext about male/female relationships – from Humbert Humbert’s attraction to the immature, pubescent Lolita to Barry’s contemptuous disdain of Lady Lyndon. Implicit in the process of remaking these boys in Full Metal Jacket into soldiers is the idea that every one of them actually has an innate duality, a nature made up of both the male and the female, with the female being a source of “weakness” – that is, an empathy which interferes with the soldier’s work of killing. Here, late in his career, Kubrick seems to be approaching an analysis of the anxiety which underlies the assertion of masculinity in many of the characters in his work. In making these boys into “men”, Hartman’s task is not merely to repress this side of their nature, but to obliterate it completely.

But there’s a risk in this. The killing instinct must remain subservient to the needs of the military organization so that it can be directed and used against the enemy. In the case of Pyle, the weak country boy’s personality lacks the strong male side that can be reinforced with group bonding. He gains the killer instinct but there’s no countering control; he ends up exploding before he gets to the war zone, killing Hartman and then himself on the eve of departure.

In country

The jump to Vietnam – unlike Cimino’s abrupt cut from morning mist on forested hills to the chaos of jungle battle – goes from the shattered Private Pyle sitting on a toilet with his bloody brains splattered on the pristine tiles behind him to a busy street with posters looming over the traffic and a Vietnamese prostitute walking resolutely towards a sidewalk cafe where Joker sits with his photographer partner Rafterman (Kevyn Major Howard). Vietnam is immediately established as “female”, the uncertain balance of power revealed in the bargaining over price for the hooker’s services. There are really only three Vietnamese characters in the film – two hookers and the final sniper – all of them female, the first two reinforcing the soldiers’ sense of themselves as unequivocally male, the last calling that identity into serious question.

The second section of the film emphasizes the casual brutality of the war, the men bonding with each other while banishing all sense of empathy for the Vietnamese. A young soldier complains that he doesn’t understand why the locals show no gratitude to the Americans for coming there to “help them”; yet we see a helicopter gunner amusing himself by shooting peasants in the fields below, joking that “anyone who runs is VC; anyone who stands still is well-disciplined VC”. Joker is told by his Stars & Stripes editor to make up stories about enemies killed and successful missions, to leave the “negative stuff” (i.e the truth) to the disloyal civilian press. The cynicism of those in charge serves to reinforce the anger and contempt of the soldiers towards the Vietnamese.

The final act of the movie involves Joker out on patrol in Hue during the Tet Offensive with a platoon commanded by his boot camp buddy Cowboy (Arliss Howard). This is perhaps the biggest distinction between Kubrick’s film and all other Vietnam movies: instead of the jungle, we see urban warfare (quite remarkably shot in a derelict area of London’s East End). Instead of the semi-mystical heart-of-darkness tone of so many Vietnam movies, Kubrick raises echoes of other more familiar wars, particularly the shattered cities of World War Two Europe. This serves to defamiliarize the war from the ubiquitous jungle news footage we’ve seen so much of and to generalize the conflict so that it stands as a sign for the behaviour of soldiers in all wars. (Steven Spielberg, an admirer of Kubrick’s work, was obviously influenced by this when making Saving Private Ryan [1998].)

The patrol, lost in the ruins, finds itself pinned down by an unseen sniper. The men fire wildly at the surrounding buildings and Cowboy loses his authority in the confusion. In the end, it’s Joker and Rafterman, both unused to actual combat, who find the sniper. Joker’s gun jams and Rafterman saves him by shooting what turns out to be an adolescent girl. Here, a committed pre-sexual female has shattered the group, killing three of the men and reducing the others to fear, panic and uncertainty. The “girl”, which Hartman was determined to obliterate in each recruit’s individual personality, here resurfaces to violently call their masculinity into question.

As they stand in a circle around her, looking with curiosity and confusion at this “enemy”, she begs for them to shoot her. And for the first time Joker fires his gun and kills, paradoxically now in an act of conflicted compassion (the aggressive Animal Mother [Adam Baldwin] says that they should just leave her there to die with the rats). But this act, with Joker finally becoming what Hartman was determined to make him, a man who has obliterated the weak female inside himself, fails to produce the intended effect.

Rather than this encounter with the enemy reinforcing the masculinity which Sergeant Hartman had worked so hard to instill in them, Full Metal Jacket ends with the platoon marching into the night singing the Mickey Mouse Club anthem while in voice-over Joker says that he is no longer afraid. Stripped of the “feminine”, the “masculine” can’t be sustained and they finally retreat into a kind of childish denial of the harsh reality they’ve been trapped in.

Reception

As previously mentioned, many critics see the film as somehow broken, often praising the boot camp section while criticizing the Vietnam section as shapeless and confused. This is perhaps an inevitable problem with any work which is structured around its themes and ideas rather than a distinct narrative line. While the first part depicts the relentless attempt to impose a rigid sense of order on human behaviour, the second half depicts chaos, a series of fragmentary experiences – sex, violence, massacres, individual death – which refuse to cohere into a single dramatic line.

The false sense of order can’t contain actual human behaviour and experience. Joker is split (“Born to kill” written on his helmet, a peace sign badge on his jacket); Rafterman, desperate to get into combat and shoot someone, vomits when he witnesses the helicopter gunner killing peasants below – and then is elated at having shot the girl sniper. These guys are caught in an insane situation and there really is no coherent response available to them.

It seems odd that someone like Roger Ebert can complain that Full Metal Jacket lacks the “realism” of Platoon, The Deer Hunter and Apocalypse Now – all films which are steeped in symbolism and metaphor – while many former soldiers apparently view Kubrick’s film as one of the most accurate cinematic depictions ever made of the experience of war, a tribute to Kubrick’s obsessive attention to detail.

Commercially, Full Metal Jacket was as successful at the box office as The Shining. And yet it would be another twelve years before Kubrick released his next, and final, film.

*

Note: In 2005 Matthew Modine published his journal and photographs about making the film as Full Metal Jacket Diary (Rugged Land: New York). Although it was a limited edition, it can still be found on-line (though some copies go for a pretty steep price). It’s a fascinating account of the long, grueling production, describing Kubrick’s working methods from the actor’s point of view, and is well worth seeking out.

Comments

Perhaps the greatest Vietnam war film, and certainly the only one with anything to say about the current wars in the middle east (it’s shot on an oil refinery!). There’s no dang romanticism in Kubrick’s work and the powerful conclusion – killing the enemy in the pretex of ending the enemy’s suffering – homes in on post Gulf War contradictions with precision.

For me it has to be FMJ Lee Emery gives a master-class in improvised acting

The story behind Gunnery Sergeant Hartman’s speech from Full Metal Jacket

https://contentforyoublog.wordpress.com/2014/06/13/the-story-behind-gunnery-sergeant-hartmans-speech-from-full-metal-jacket/