Too big to read …

Like most people who grew up with them, books mean more to me than simply the words they contain. I bought a Kindle last year, and I have dozens of books on it, but mostly it sits untouched on a shelf. I’ve only really used it on my trips to Beijing last year and England this past summer. There’s no denying the convenience it offers when travelling. But at home, I do most of my reading the old way.

There’s something almost mystical about the object itself, the words there on the pages even when the cover’s closed, the ideas and stories almost humming as they wait to be activated by the act of reading. Strange how printed words can trigger intense emotions, cause excitement, anger, nostalgia … make you laugh out loud or feel like crying. I really don’t know how anyone can get by without reading.

When I was younger, I mostly read fiction. These days, it’s mostly non-fiction – history, criticism, politics … but whatever the content, I have a powerful attachment to books as objects and the collector in me is sometimes drawn to what I’d call too-big-to-read books. These are hefty tomes about subjects that interest me, but which are so unwieldy that I somehow never quite manage to read them, though I’ll sometimes take them off the shelf, open them up and browse and skim for a while before putting them back.

For actual reading, I need something more manageable, more portable … something I can take from room to room, read lying on the couch or in the bath, on the bus to work or during a coffee break. But these large volumes steadfastly refuse to lend themselves to that kind of convenience; they demand subservience, dictating their own terms. I can’t help but rebel against their demands, and yet their very intransigence and inaccessibility is what makes them such prized possessions.

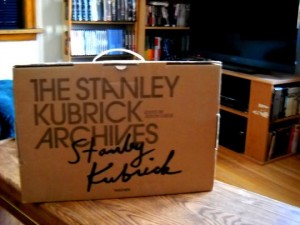

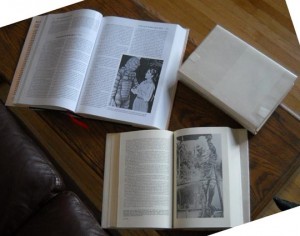

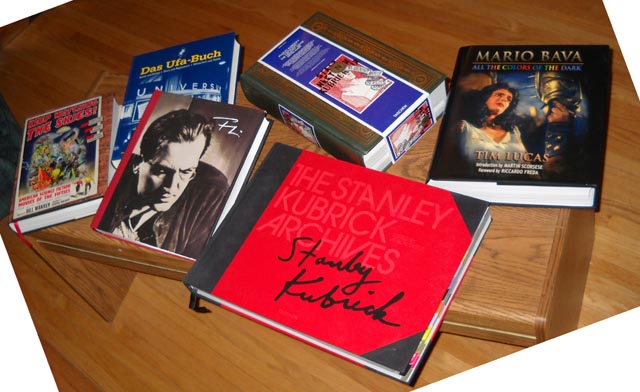

Not surprisingly many of them are film-related – some only tangentially, like Leni Riefenstahl’s massive collection of photographs of the Nuba, called simply Africa. This was published by Taschen, which also published the massive Stanley Kubrick Archives (edited by Alison Castle), so large and weighty that it comes in its own “suitcase” complete with handle to facilitate carrying.

The Kubrick volume is rich in photographs from the director’s films, but also from his life and behind-the-scenes work. Each film gets critical and documentary treatment and it’s well worth dipping into the book to get background and context – but spread open, it’s literally as large as my coffee table and refuses to permit sustained reading.

Then there’s Taschen’s 1200-page one-volume edition of their earlier 10-volume set about Stanley Kubrick’s Napoleon: The Greatest Movie Never Made (also edited by Alison Castle). This contains Kubrick’s original script and extensive research notes, interviews and countless pictures which represent just a fraction of the visual material he accumulated over the years relating to the Emperor and his times (the book includes a “key card” which gives the buyer access to a complete on-line archive of all this material, thousands of images, guaranteed to produce a feeling of exhaustion and ennui if you spend too much time browsing through it). Tall and thick, this scrapbook offers a window into Kubrick’s creative process, but it’s incredibly awkward to handle.

Somewhat smaller than the Kubrick Archives is Fritz Lang: His Life & Work: Photographs and Documents (jovis, 2001), edited by Rolf Aurich, Wolfgang Jacobsen and Cornelius Schnauber, published in association with the Filmmuseum Berlin to accompany a retrospective of the director’s work. Here again, the book contains a rich selection of photographs dealing with the films and the filmmaker’s life and work, along with extensive quotations from articles, essays and letters by Lang himself and others, which illuminate not only the films but also the personality of the filmmaker (in three languages – German, English and French – printed in parallel columns). Too much for sustained reading, but useful to dip into to get some insights into individual films.

About the same size as the Lang volume is a richly illustrated history of the UFA studios which I bought on a trip to Switzerland in 1993. The problem with Das Ufa-Buch, by Hans-Michael Bock and Michael Toteberg (Zweitausendeins, 1992), is that it’s entirely in German and seems never to have been translated and published in English. When I bought it, I had some kind of ambition to make the effort to learn how to read German, but I never got around to it. Which is too bad because the studio’s history from its origins in 1917 up to the present day is remarkably rich. Still, it’s worth browsing just for the beautifully reproduced photographs of the great days of Weimar cinema and the ensuing Nazi years.

Bill Warren’s classic study of science fiction films, Keep Watching the Skies, was first published by McFarland & Co in two volumes in 1982 and 1986. Dense, entertaining and well-informed, this quickly became one of my favourite film books, which I read cover to cover, and often returned to over the years to get information about individual movies from the 1950-63 period he covers as more and more of them became available on VHS and later DVD. Naturally, I had to buy a copy of the revised edition when it came out in 2010. But although that new edition was produced on a more lavish scale, glossy paper improving the quality of photo reproduction, with many of the essays expanded with new material gathered in the intervening quarter century, the large format single volume makes it far more unwieldy than the original two volumes and I have to confess that it’s usually to that earlier version that I turn when I’m looking up information about a particular film.

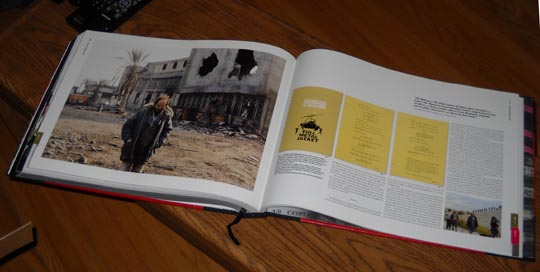

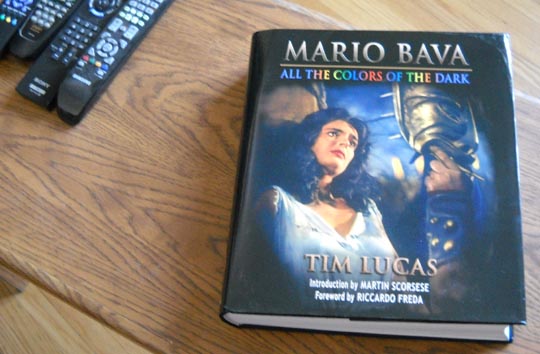

Finally, there’s Tim Lucas’s daunting labour of love, Mario Bava: All the Colors of the Dark, published by Video Watchdog in 2007 after years in the writing. I’d seen references to this book for years and often checked on Amazon to see if it was out yet. I finally pre-ordered it from VW more than a year before it eventually came out (you can find my name among the hundreds of “patrons” printed at the back of the book) and wasn’t disappointed when it turned up on my doorstep weighing more than ten pounds and 1100+ glossy pages long. It’s an eye-popping volume, loaded with images from Bava’s films and of course countless pictures of the director at work. But what really impresses is the sheer density of Lucas’s text … decades of research distilled into a fascinating, detailed account of Bava’s life and astute critical evaluations of the films.

But the truth is, I haven’t read the book, just dipped into it, because it can’t be held; you have to sit hunched over it at a table and each chapter demands hours of attention … maybe I could have managed it when I was younger, but these days I have to get up and move around after a brief spell of that kind of concentration. Of all the books mentioned here, this is the one I really want to read from cover to cover – I have in the back of my mind the project of re-watching each of Bava’s films in conjunction with reading the relevant chapter in the book – but that represents a huge commitment in time and energy. Maybe if the text ever becomes available for Kindle download[1] I’ll finally do it … but for now, I’ll just have to take the book down from the shelf every now and then and flip through the pages, feeling the weight of it, the impressive scale of Lucas’s ambition, reading a page here and there and admiring the obsession which can bring such an artifact into being.

_______________________________________________________________

(1.) Lucas did eventually release All the Colors of the Dark in digital format and, although I was a bit annoyed that he didn’t offer it free to people who’d previously bought the book, I coughed up another thirty bucks for the download – but it still took me several years to get around to reading it, mostly on my tablet during my bus commute to work over a period of two to three months; the effort was well worth it as Lucas’ work enriches the watching of all of Bava’s movies by illuminating the challenges he faced and the ingenious ways he always found to overcome them. (return)

Comments