Stanley Kubrick 8B: Male Anxiety and Marriage – Eyes Wide Shut (1998)

When Stanley Kubrick’s movies were released on Blu-ray back in 2011, I decided it was time to watch them all again in chronological order. In part to remind myself of just why he’d been important to my sense of film for over forty years, and in part to see what patterns I could discern in the work of a director so obviously obsessive about his chosen medium. Although I thought I’d get through the films quite quickly, I’m embarrassed to see that it’s actually taken me 15 months to watch and consider all thirteen of his features – slightly less than one a month! In fact, it’s just about three months since I posted my thoughts on Full Metal Jacket and I have to admit that, although the prospect of watching Eyes Wide Shut again certainly didn’t seem as onerous as slogging through Spartacus one more time, I didn’t feel a lot of enthusiasm for it.

Perhaps it’s simply because Eyes Wide Shut was Kubrick’s final movie that it seems so problematic. I know that when I first saw it in 1999 the fact that he had died just as it was being finished put impossible expectations on the film. Whether it’s conscious or not, we have a tendency to expect any artist’s final work to somehow be a summation, a final statement in terms of both themes and aesthetics … but probably very few artists begin a project thinking that “this will be my last testament”; they’re just continuing what they’ve been doing all along. And maybe we feel slightly cheated. Just remember how disappointed a lot of people were with Hitchcock’s Family Plot (1976), a light and charming comedy thriller which revealed him to be relaxed and confident in his work, but hardly concerned with creating a culminating monument to a fifty-year career.

Eyes Wide Shut was released twelve years after Kubrick’s previous film, Full Metal Jacket, one of his finest. In the interim, he’d tried to get a number of projects started and had spent several years simultaneously developing Eyes and AI. He finally decided to pass the latter on to Steven Spielberg because he felt that there was a danger of him approaching the material in too coolly an intellectual way, while it would need some counterbalancing emotion. In Spielberg’s hands, of course, it went too far in the other direction, sinking beneath the weight of mawkish sentimentality.

Instead, Kubrick pursued a “small” personal story, based entirely on character (though expanded to epic length), which finally addresses directly issues of gender and sexuality which had run tangentially through much of his previous work.

Eyes Wide Shut (1999)

Eyes Wide Shut was based on Traumnovelle (Dream Story), a 1926 novella by Arthur Schnitzler. This in itself doesn’t seem unusual; after his apprentice works, Fear and Desire and Killer’s Kiss, all of Kubrick’s films were based on literary sources, and a very eclectic selection they were. From pulp novels to classics, popular fiction to the “impossible to film”. Frequently the original source would simply be a jumping off point – Dr Strangelove bears little resemblance to Peter George’s novel Red Alert; 2001: A Space Odyssey took off from The Sentinel, a very slight short story by Arthur C. Clarke; Lolita and The Shining took liberties with their sources … but Eyes Wide Shut is striking for being an almost slavishly faithful adaptation.

The script that Kubrick wrote with Frederic Raphael (Darling, Two For the Road, Far From the Madding Crowd, Daisy Miller) follows Schnitzler’s story remarkably closely – apart from the shift from turn-of-the-century Vienna to 1990s New York, and the invention of Victor Ziegler, the character played by director Sydney Pollack (a rather clumsy device used to “explain” the hallucinatory experiences of Dr. Bill Harford), there are only two significant divergences from the source, in both cases the omission of an important narrative element. The essence of Schnitzler’s story is the conflict between the psychological and social constraints of bourgeois marriage and the almost uncontainable energies of the libido; the forces of sexuality virtually overwhelm the complacency necessary for the doctor to function as a satisfied married man. That is, the forces of female sexuality embodied in his wife threaten his equilibrium.

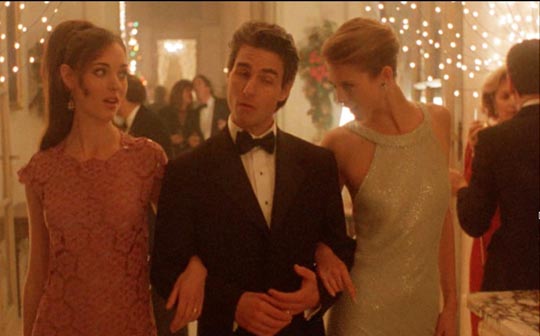

Bill Harford and his wife Alice (Fridolin and Albertine in the original story) are physically and emotionally comfortable with one another in their large, expensive New York apartment. Leaving their young daughter with a babysitter, they head for an opulent pre-Christmas party thrown by Ziegler. While Bill chats up a pair of models, Alice dances with a rather overbearingly decadent aristocrat who insists that she should have an affair. When Bill disappears – called upstairs by Ziegler to deal with a woman’s drug overdose – Alice suspects he’s gone to have sex with the models and drinks too much champagne while fending off her suitor.

Back home, late at night, a discussion of their mutual temptations turns into an angry attack by Alice on Bill’s complacent attitudes towards her sexuality:

Alice: And why haven’t you ever been jealous of me?

Bill: Well, I don’t know, Alice. Maybe because you’re my wife, maybe because you’re the mother of my child and I know you would never be unfaithful to me.

Alice: You are very, very sure of yourself, aren’t you?

Bill: No, I’m sure of you.

This provokes Alice to describe an experience she had the previous summer, when she felt an almost overwhelming desire for a stranger she saw across a hotel lobby; she tells Bill that if the man had given her any sign she would have dumped him and their child in a moment. The ferocity of her feelings fills him with insecurity.

(In the script’s first important divergence from Schnitzler’s story, Kubrick and Raphael cut Fridolin’s countering erotic anecdote about an encounter with a 15-year-old girl on the beach during the same holiday. By removing this equivalence, the adaptation heightens the focus on male sexual anxiety.)

Deeply unsettled by the intensity of Alice’s outburst, Bill is called away to the home of a patient who has just died. With the man lying there in his bedroom, his daughter Marion (Marie Richardson) tells Bill that she’s desperately in love with him. She kisses him and he responds – but just then her fiance arrives and Bill quickly leaves.

Reluctant to return home, he wanders the streets and is picked up by an attractive young prostitute (Vinessa Shaw) who takes him back to her apartment. The awkward moment is interrupted by a call from Alice on his cell, asking how late he’s going to be. This intrusion makes it impossible to go through with whatever might have been about to happen and he leaves. (In the original story, pre-cell phone, a combination of fear and guilt makes it impossible to go through with the encounter.)

Reluctant to return home, Bill goes to a bar where he bumps into an old college friend, Nick Nightingale (Todd Field), playing piano. Nick lets slip that he’s scheduled to play at a private event later that night, a party where there will be a lot of attractive, probably naked women. Bill manages to get the password from him and heads to a costume shop where he’s previously treated the owner. The shop is now in the hands of Milich (Rade Sherbedgia), a slightly creepy guy who interrupts their transaction when he angrily discovers his young daughter (Leelee Sobieski) playing sexual games in a back room with a pair of much older Japanese men.

Bill rents a cape and mask and follows Nick in a taxi to a large estate just outside the city where the password gets him admission to a strange orgy. The people are dressed as if at a Renaissance ball, giving the whole thing a peculiarly religious air. It’s clear that Bill is spotted as an interloper, but when a woman urgently whispers to him that he should leave while he still can, he dismisses the idea that he’s in any danger. He wanders from room to room where couples and groups form sexual tableaux. And eventually he’s led to a large chamber where he faces a kind of tribunal; but before whatever sentence they have in mind is passed, the woman who warned him offers herself as a substitute sacrifice and he’s hustled out into the night.

Finally arriving home, Bill wakes Alice from a dream which has left her deeply upset. Her description sounds like a reflection of his experience at the mansion – an orgy in which she has had sex with countless men, knowing that Bill can see her and wanting to humiliate him … This is the second place where the script partially omits an important element of Schnitzler’s story, because in the original Albertine is far more brutal to her husband. While she discovers an exhilarating sense of freedom and joy in this wild sex, in her dream Fridolin clings to a sense of loyalty to her and ends up brutally flayed and finally crucified. She ends her account by saying: “I wanted you at least to hear my laughter while they nailed you to the cross. – And so I burst out laughing as loudly and piercingly as I was able. That was the laughter, Fridolin – with which I woke.”

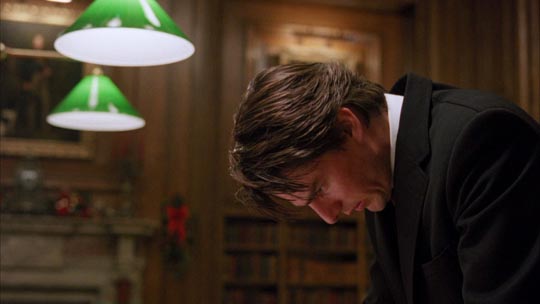

Structurally, the film echoes A Clockwork Orange in having Bill revisit the site of each encounter the following day: he looks for Nick Nightingale, but discovers that he’s disappeared from his hotel, bruised and in the company of two men; he goes back to the costume shop and finds that Millich, so angry with his daughter the night before, has reached an “accommodation” and is now prostituting her to the Japanese; he finds the mansion again, where a servant hands him a note saying that for his own good he should terminate his enquiries; he goes to the prostitute’s apartment where a roommate tells him she’s gone and may never be back – she just learned she has AIDS; then in a cafe he reads in the paper that an “ex-beauty queen” has died of a drug overdose, which leads him to the morgue where he finds the woman who offered herself at the mansion as a sacrifice in his place … at which point he gets a call from Ziegler and, going to his home, gets everything explained.

Structurally, the film echoes A Clockwork Orange in having Bill revisit the site of each encounter the following day: he looks for Nick Nightingale, but discovers that he’s disappeared from his hotel, bruised and in the company of two men; he goes back to the costume shop and finds that Millich, so angry with his daughter the night before, has reached an “accommodation” and is now prostituting her to the Japanese; he finds the mansion again, where a servant hands him a note saying that for his own good he should terminate his enquiries; he goes to the prostitute’s apartment where a roommate tells him she’s gone and may never be back – she just learned she has AIDS; then in a cafe he reads in the paper that an “ex-beauty queen” has died of a drug overdose, which leads him to the morgue where he finds the woman who offered herself at the mansion as a sacrifice in his place … at which point he gets a call from Ziegler and, going to his home, gets everything explained.

In Schnitzler’s story, Fridolin visits the morgue to see the suicide he’s read about in the paper, but because he never saw the woman’s face at the party, he can’t be sure she’s the one on the slab. It’s left ambiguous whether this death is the result of his infiltration of the orgy, but he decides to tell himself that it is, that she was sacrificed to save him. In the film, Ziegler explains it away – yes, she was the same woman, but the OD was entirely coincidental (she was the same woman Bill treated for an OD at Ziegler’s Christmas party); there is no sinister conspiracy, just an attempt to scare Bill off and make sure he doesn’t dig into the secret doings of a bunch of rich people who like to play kinky games.

Exhausted, Bill returns home, where he breaks down and says that he’ll tell Alice everything … both story and film end with the couple realizing that life is full of dreams, experiences, desires and fears and that they simply have to navigate all these things, be aware, and accept each other’s complex natures.

Male Anxiety Laid Bare

What drew Kubrick to this story? Sexual relationships, and particularly marriage, never played a major role in his work – and when they do show up, they’re problematic. The Peattys in The Killing, trapped in a hateful marriage, tearing each other apart; Humbert marrying Charlotte Haze simply to get close to her adolescent daughter, Lolita; Barry marrying Lady Lyndon purely for the social advantage and treating her with contempt as he squanders all her money; emotionally fragile Wendy tormented by the monster Jack in The Shining … it runs through Kubrick’s work, this sour and unhappy view of marriage, and by extension male/female relationships.

In Full Metal Jacket, the reasons behind this began to surface with that film’s analysis of masculinity defined as an aggressive resistance to “female” traits which suggest weakness and vulnerability. Male and female are in constant conflict and the male exists in a state of anxiety resulting in aggression. Eyes Wide Shut focuses on this state, taking Bill Harford, a successful, wealthy professional, and exposing his fears.

Throughout the film, women are the sexual actors while Bill is purely reactive, in fact seemingly unable to “perform”; everywhere he goes he’s confronted with a lack of female inhibition – at a father’s deathbed, in a prostitute’s apartment, at the costume shop, finally at the orgy where he’s surrounded by statuesque naked women, while the men wear monk-like cloaks and hoods. And, of course, in his own home where Alice attacks him with revelations of her own sexual desires, which aren’t actually attached to him. Even at the end, as they reach a kind of understanding of the emotional and psychological quicksand on which their marriage rests, it is Alice who remains the active member of the pair – she has the final word:

Alice: But I do love you and you know there is something very important we need to do as soon as possible?

Bill: What’s that?

Alice: Fuck.

Throughout Kubrick’s work, we can see men struggling to assert themselves, to impose some kind of control over their world … an effort which paradoxically reveals the essential weakness of their nature: Davey Gordon in Killer’s Kiss; Johnny Clay in The Killing; Colonel Dax in Paths of Glory; Spartacus; Humbert Humbert in Lolita; General Ripper, General Turgidson, President Muffley and Dr Strangelove; Dave Bowman in 2001; Alex and Dr. Brodsky in A Clockwork Orange; Redmond Barry in Barry Lyndon; Jack Torrance in The Shining; Joker in Full Metal Jacket. I’m not sure whether Kubrick’s attitudes had mellowed by the time of Eyes Wide Shut, or whether it’s the new focus on the character’s individual psychological experiences which make the film’s ending seem perhaps a little more hopeful than usual … but Bill Harford remains a very passive character to the end.

Throughout Kubrick’s work, we can see men struggling to assert themselves, to impose some kind of control over their world … an effort which paradoxically reveals the essential weakness of their nature: Davey Gordon in Killer’s Kiss; Johnny Clay in The Killing; Colonel Dax in Paths of Glory; Spartacus; Humbert Humbert in Lolita; General Ripper, General Turgidson, President Muffley and Dr Strangelove; Dave Bowman in 2001; Alex and Dr. Brodsky in A Clockwork Orange; Redmond Barry in Barry Lyndon; Jack Torrance in The Shining; Joker in Full Metal Jacket. I’m not sure whether Kubrick’s attitudes had mellowed by the time of Eyes Wide Shut, or whether it’s the new focus on the character’s individual psychological experiences which make the film’s ending seem perhaps a little more hopeful than usual … but Bill Harford remains a very passive character to the end.

The Style

Perhaps Kubrick’s casting choices have something to do with this. He was a director who obviously loved actors – sometimes to a degree detrimental to a particular film. His fascination with a performer would sometimes lead him to indulge the actor’s ego. Peter Sellers is amusing, but nonetheless a jarring note in Lolita; Kubrick harnessed the actor’s anarchic personality to far greater effect in Dr. Strangelove. Jack Nicholson derails The Shining with his inability to play an ordinary man who goes mad – he starts in full-blown maniac mode and proceeds to escalate from there. But in films like A Clockwork Orange and Full Metal Jacket, Kubrick was able to guide large ensembles in near-perfect balance, fully attuned to the overall tone of the movie as a whole.

And then there were unexpected choices, like Ryan O’Neal as Barry Lyndon, with Kubrick guiding this rather light-weight star to the best performance of his career, integrating the actor’s own shallowness into the character’s personality to create a portrait of vacuous social ambition perfectly in tune with Thackeray’s satire.

Perhaps he had some similar intention in casting Tom Cruise as Bill Harford, but Cruise seems to be out of his depth here. Effective as cocky, immature guys, Cruise generally has a hard time playing a real adult and here he isn’t terribly convincing as a rich and successful society doctor. Although there’s a thematic justification for his passivity in the face of Alice’s attack, he unfortunately appears to be out of his league in their big scenes together. Simultaneously, Kubrick indulges Nicole Kidman as Alice; her drunkenness, her anger, her distress all seem overly actorly; the big argument scene after the party has the air of a drama school exercise, over-emphatic and superficial rather than deeply felt.

But this is something which might be said of the film as a whole. While Eyes Wide Shut displays many of Kubrick’s visual strengths, his camera gliding through the large, opulent sets and the slightly unreal streets of New York, scenes frequently lie static on the screen, mere narrative markers rather than dramatized moments. The emphasis here is more on dream than realism, with scenes like those in the costume shop having a kind of Lynchian absurdity. But there’s an oddly chilly feeling to the scenes in the mansion which completely de-eroticizes the orgy, working against the film’s sexual themes. Instead of offering Bill Harford a vision of wild abandon, it all seems mechanical and joyless. You get the feeling that Kubrick perhaps wasn’t entirely comfortable with the material.

Eyes Wide Shut seems far longer than its narrative warrants, with many scenes slackly playing on after they’ve made their point. I felt myself becoming impatient during the opening party as the conversation between Alice and her dancing partner went on and on, reiterating its point as Kidman played the giddy drunk. None of Bill’s encounters can comfortably sustain their length, and one wonders whether Kubrick really had finished the editing before he died. Certainly, we know that Warner Brothers interfered with the film after the director’s death, imposing ridiculous digital censorship over the orgy sequence.

Would Eyes Wide Shut work better if more tightly edited? That’s impossible to say now, although I doubt further editing would really help to give Cruise’s performance more substance. Although it may seem disappointing that Kubrick ended his career with something less than a masterpiece, it finally doesn’t detract from the fact that, while he only completed 13 features in 46 years, a remarkable number of them are great movies, and several more are fascinating if flawed lesser works … a body of work matched only by a select few filmmakers.

*

Frederic Raphael, by the way, wrote a somewhat embittered memoir about working on the film with Kubrick. Apparently he didn’t find the experience very satisfying and takes the opportunity (after the director’s death) to use Kubrick as a bit of a punching bag. Eyes Wide Open seems to be out of print, though used copies are easily found on-line.

Comments

Let’s talk about it 20 years from now. Eyes Wide Shut is one of Kubrick’s best 3 movies.

Well, maybe in 20 years I’ll agree … who knows, maybe even sooner. I haven’t rewatched it in three years.