Blu-ray Review: The Awakening (2011)

In the past few years, something interesting has been happening in the horror genre. After several decades of increasingly graphic movies focused on the torture and destruction of the human body, something more subtle has been re-emerging. Like it or not, one of the key instigators of the trend was The Blair Witch Project (1999); more recently, the Paranormal Activity series and its imitators have leaned heavily on suggestion rather than graphic depictions of horror. For a traditionalist, these movies come as a relief … the uneasiness generated by them lingers longer than the revulsion caused by endless depictions of mutilation offered in the Saw movies or Hostel and their ilk.

Not surprisingly, this trend has brought about a resurgence of the traditional ghost story, narratives which offer a more metaphysical view of death and the shadow it casts on the living. And as so often is the case with classical ghost stories, many of these movies centre on the deaths of children – like Guillermo Del Toro’s The Devil’s Backbone (2001) and the recent Woman In Black. This aspect of the tradition carries a deep sense of psychological unease rooted in our innate sense of personal mortality.

The psychological dimensions of the ghost story go back a long way, perhaps most clearly considered by Henry James in The Turn of the Screw, brilliantly filmed by Jack Clayton as The Innocents in 1961, and Shirley Jackson in her 1959 novel The Haunting of Hill House, equally brilliantly filmed by Robert Wise in 1963 as The Haunting. To this lineage can now be added Nick Murphy’s The Awakening (2011), a film steeped in traditions of the classic British ghost story.

Set in 1921, a “time for ghosts” as Florence Cathcart (Rebecca Hall) says, in a nation traumatized by the mass deaths of the First World War and the great influenza epidemic which followed it, the spectre of death permeates every image. Florence, a very modern woman and a rationalist, suppressing her personal grief at the death of her fiance in the war, spends her time debunking the idea of survival after death. The film opens with a spiritualist seance which she disrupts, exposing the fraudulent tricks used to mislead and exploit gullible people looking for reassurance from “the other side” (at that time, seances were still illegal under the vagrancy and witchcraft statutes which lingered from an earlier time). But Florence is attacked by a woman who believed she was seeing her own dead child during the seance; the woman would rather be duped with comforting lies than face the absolute loss of her daughter.

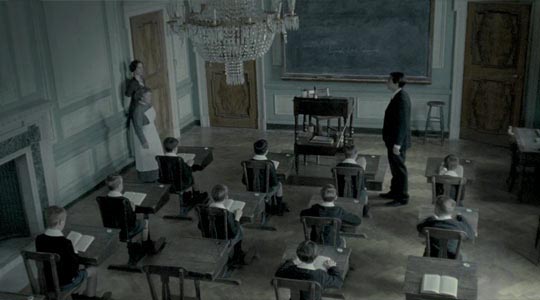

As Florence, emotionally exhausted, returns home after the fake medium has been arrested, she finds a man on her doorstep who says he needs her help with what appears to be a genuine ghost. Mallory (Dominic West) is a former soldier, now a teacher at a remote boys’ boarding school in the country where a few weeks earlier one of the pupils apparently died of fright after seeing the ghost of a boy reputedly murdered there many years earlier.

Despite her initial refusal to become involved, Florence soon arrives at the school, a huge old country estate full of echoing rooms and passageways. Everyone she meets there is damaged in some way – Mallory and another teacher, McNair (Shaun Dooley), were both in the war and still suffer what we now call PTSD, though back then it was “shattered nerves”; the school’s handyman Judd (Joseph Mawle) is plagued by guilt for having avoided the war and anger at the barely concealed contempt of the ex-soldier teachers; the housekeeper Maud (Imelda Staunton) seems extremely sensitive to the cruelties of the boys who bully and torment the weaker among them; and Tom (Isaac Hempstead Wright), one of these lonely boys, is forced to stay on at the school as the rest leave for home with their parents during a school term break.

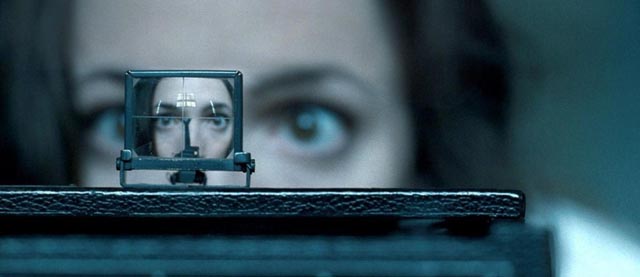

As Florence places her various pieces of scientific equipment around the school in the days before the break, she is certain that she will expose pranksters among the boys … and quite quickly uncovers a rational solution to the pupil’s recent death. But her discovery of what happened devastates her and it becomes apparent that all her efforts to debunk ghosts conceal a deeper desire to uncover actual evidence of survival – she uses her intellect to search for a justification to believe something which goes against everything she holds to be true.

And that’s when the genuine manifestations begin and she starts to be drawn into a deeper mystery which has devastating implications for her personally.

The Awakening is steeped in atmosphere, the cool, muted colours of Eduard Grau’s cinematography giving it a damp and chilly tone which reflects the crushed emotions of all the characters. It’s a film full of pain and fear which is rooted in the finely detailed psychology of the characters. The performances are uniformly excellent and, like many classic ghost stories, the overall effect is more of sadness than horror. In fact, perhaps the weakest element of the film is the ghost itself, which apart from a few brief shocks, is presented in a prosaic manner leading to a climactic revelation of suppressed memories which is almost cliched, although very well staged.

(*Spoilers*) The ghost actually doesn’t work very well – at least not for me. While for certain reasons Florence can see him clearly (so clearly that she doesn’t realize he is a ghost), he’s also continuously visible in scenes with other characters and although Murphy claims that he was careful to make sure that overheard conversations with the ghost would “make sense” to other characters who would only be hearing Florence’s side, this isn’t very convincing. In fact, when she bares her heart to the ghost about her dead fiance and the way she treated him and this is overheard by Mallory from outside the room, her monologue would seem very bizarre if, as Mallory would think, she was alone in the room. This awkwardness may simply be a result of Murphy’s impatience with genre conventions, and the climactic revelations about Florence’s own past play more convincingly as manifestations of her own liberated memory than as actual spectral events.

And yet, while the film lacks the creepy thrills of, say, Andrés Muschietti’s Mama (2013), it has a deeper and more resonant impact because of the psychological richness of the material, harking back to the literary chills of James and Jackson.

*

The disk

The Blu-ray captures the subtlety of Grau’s images in a chilly 1080p, 2.35:1 transfer which is rich in detail, with the muted colour scheme occasionally punctured by a sudden splash of red. The 5-channel audio is equally subtle, capturing the ambience of the vast, almost deserted house, occasionally disturbed by a distant sound – the small alarm bells Florence places across doorways, muffled and echoey voices from a distant room. This is a quiet, stately film which demands that its audience be attentive and observant.

The extras

The disk is loaded with almost 2½ hours of extras, most of them interview-based. Director and co-writer Nick Murphy obviously enjoys talking about his work: there’s a selection of brief deleted scenes which are stretched out to 28:13 by his lengthy introductions, explaining their context and his reasons for removing them, plus an additional interview (19:28) about his reasons for making the film.

A Time For Ghosts (24:46) features interviews with Murphy, Hall, and West as well as Juliet Nicholson, author of a book about post-WW1 social trauma, and Alan Murchie, chairman of The Ghost Club, discussing the impact of the years of mass death which form the film’s backdrop. Anatomy of a SCREAM (17:12) features the director, his three stars, producer David Thompson and Murchie again discussing their belief – or disbelief – in ghosts. Behind the Scenes (36:02) is a collection of interviews about the actual shooting of the film, while Anatomy of a Scene: Florence & the Lake (15:16) looks at the logistics of shooting a scene involving actors being plunged into very cold water for a pivotal scene.

*

PS: The mystery credit

Although Nick Murphy talks a great deal in the extras about making the movie, he repeatedly speaks of “my script” … with no mention of Stephen Volk who shares the writing credit. Actually, I was initially drawn to the film because Volk’s name was on it. He’s an interesting writer, with a history of genre credits dating back to Ken Russell’s typically idiosyncratic Gothic, a treatment of the famous party in Switzerland which gave rise to Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein; the great proto “reality” horror Ghostwatch which predated Blair Witch by seven years while harking back to Nigel Kneale’s brilliant The Stone Tape (1972); and the excellent BBC series Afterlife (2005-06), which places some of the central themes of The Awakening in a contemporary setting.

Yet apart from that credit at the beginning of the film, there’s no sign or mention of Volk anywhere on the disk. You have to search the Internet to discover that the film has its origins in a script which the writer worked on for 15 years, taking James’ Turn of the Screw as his starting point, with a grown up Flora as the protagonist dealing with the fall-out of the events in James’ story which culminated in the death of her younger brother Niles.

Volk: I suppose deep down in this film I was playing with ghosts and memory being the same thing. Memory externalized. I like the idea, I think the idea is essential, that ghosts appear for a purpose and that purpose is embedded in the character, their fatal flaw, and that’s what you are dramatizing. Good old John Carpenter says horror is the internal made external. I’d agree with that. Furthermore, I’d say, if it isn’t, why the hell are you writing it? If it’s not about character, the genre is just jumps and gore and “that’d be cool”. I’m not interested in “that’d be cool”.

In several interviews published on-line Volk is very gracious about what Murphy ultimately did with the material, which makes the director’s silence – or rather his taking full, sole credit for the script – all the more puzzling, not least because he admits that he has no particular interest in the horror genre and thinks that ghosts are “bunkum”. Whatever the reasons, his omission of any acknowledgement of Volk’s contribution to The Awakening seems to reflect rather poorly on him.

Comments