Miscellaneous Thoughts

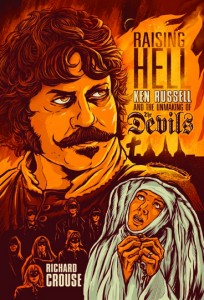

I recently picked up a copy of Raising Hell: Ken Russell and the Unmaking of The Devils by Richard Crouse (ECW Press, 2012). It’s a breezy read recounting the production history and subsequent fate of Russell’s 1971 masterpiece (perhaps a little too breezy: Rouse confuses Russell’s Isadora Duncan, the Biggest Dancer in the World [1966], made for the BBC, with Karel Reisz’s feature Isadora [1968], for which Vanessa Redgrave received an Oscar nomination). Drawing on interviews with a number of the surviving participants, Rouse does a good job of recounting what happened and why – but what I was hoping to find was some clear explanation of Warner Brothers’ continuing abuse of the film more than forty years after it was made, despite the fact that many critics and fans now recognize it as a powerful, serious work of film art.

But all he comes up with is second-hand opinions pinning the blame on Alan Horn, president and CEO of Warners, a conservative who doesn’t want to offend the religious right in the States. But of course, there are numerous cases in Hollywood history in which companies have dealt with “problematic” movies by selling them off to less cautious companies. After all, Hollywood is primarily in the business of making money. So the fact that Warners continues to resist the commercial possibilities of Russell’s film (there are others who would happily take it over for distribution) indicates that there’s more than a fear of backlash in this; the company that happily exploited the morally dubious Exorcist really appears to take some kind of personal offence at Russell’s film.

Speaking of troubling films …

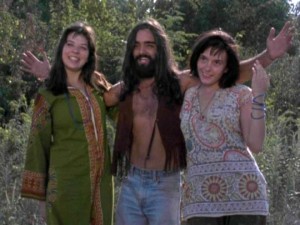

I first heard of Jim Van Bebber’s decade-in-the-making The Manson Family in late 1998 or early 1999, when I came across a copy of the script published by Hushion House as Charlie’s Family (the book is out of print and the publisher long gone, but copies are still to be found on-line). The film itself wasn’t released until some four years later and I didn’t get a chance to see it until Dark Sky brought out their 2-disk DVD in 2005. Like anyone who was fairly young when the Manson murders took place, I’d been fascinated by this mad messiah and his acolytes since the case first hit the news in 1969; the apocalyptic element of the killings as described in the media and elaborated by prosecutor Vincent Bugliosi at the trial seemed, like the Stones concert at Altamont, to signal the catastrophic end of the ’60s.

Van Bebber’s remarkable, disturbing movie – something of a corrective to the Manson myth promoted by Bugliosi in the trial and his subsequent self-aggrandizing book, Helter Skelter – is getting a 10th anniversary re-release from Severin Films, with a limited theatrical run in a number of U.S. cities through March and April, leading up to a special edition Blu-ray scheduled for May 7. Van Bebber recreates the Manson story using stylistic effects which seem to root the film completely in the late ’60s; it evokes the story from “inside” as the free love, drugs, and obsession with obliterating the ego lead to senseless and terrible acts of violence, which are portrayed in a nasty, totally unglamourized way.

There are no apparent Canadian theatrical dates, but I’m hoping to score a review copy of the Blu-ray. [I did.]

Blown Endings

My friend Steve and I get together fairly regularly to watch a couple of movies on a Saturday evening. This entails me getting a free meal from him and his wife Val, and me taking a stack of disks for him to choose from (Val doesn’t share our tastes, so seldom joins us for the viewing: the last thing she enjoyed that I took over was – much to my surprise – Adam Green’s Frozen).

Most recently, Steve picked Philip Ridley’s Heartless (2009) and Ti West’s The Innkeepers (2011) from my selection. Both are movies that I really like – up to a point; atmospheric horror, with West leaning towards the traditional ghost story, while Ridley offers an apocalyptic supernatural vision of urban decay. But what the two films have most in common are what I’d call “blown endings”.

In the case of The Innkeepers, as I pointed out in an earlier post, the problem is simply a script which fails to motivate a major character’s behaviour in the final act. There’s no question that the supernatural element is real or that the ghost in an old New England hotel is malevolent; but surely West could have found some more plausible way to get Claire (Sara Paxton) into the basement for her ultimate demise – it’s not that she gets scared to death that bothers me, but that given everything that has previously happened, she would go down those stairs once again looking for a woman who she just saw go upstairs. It’s sloppy writing, and you have to wonder why no one during the production process ever bothered to point that out and rethink it.

But there are other cases in which talented, skillful filmmakers seem to suffer a kind of narrative failure, an inability to find a satisfying ending to complete an otherwise satisfying story. Sometimes this seems to arise from the idea that a story needs a “final twist” to give the viewer one last thrill, but it’s often a twist which ruins or negates what made the film interesting in the first place. Bill Paxton’s disturbing Frailty (2001) is a victim of this. The story of two brothers whose father insists that he has a mission to destroy demons who walk among us, it’s a darkly effective tale of madness and the ways in which parents inflict terrible damage on their children. The two boys are made active participants in their father’s serial killing career – but all the psychological implications of the situation are destroyed in the final stretch when it turns out that there really are demons and the father really is on a mission to fight evil.

Heartless, which I re-watched the other day with Steve, suffers from the opposite problem. Jamie Morgan (Jim Sturgess), a socially inhibited photographer (he has a large birthmark covering one side of his face), starts seeing strange and disturbing figures in the nighttime streets of London. Vandalism and delinquency escalate as these apparent demons turn their attention on Jamie and his family. His life becomes increasingly nightmarish as a strange man, Papa B (Joseph Mawle), offers him a deal which takes away the marks on his face in exchange for some ill-defined future price; Jamie’s experiences become more violent and grotesque and supernatural … yet at the end, Ridley suddenly explains everything away and says that it was all just in Jamie’s head … except too many of the experiences can’t be coherently explained in this way, so while the apocalyptic horror is swept away, the attempt at a purely “psychological” explanation fails, leaving the film seeming unsatisfyingly incomplete.

It’s a pity, because the unsettling mood of fear and madness Ridley creates throughout the film make it one of the finest pieces of urban horror in years; the mix of violence (the terrible death of Jamie’s mother) and very black humour (the meeting with the sinister “weapons man” [Eddie Marsan]) show a strong creative intelligence, but Ridley fumbles the ending in his attempt to transform the story into a depiction of Jamie’s psychological disturbance – instead of a well-wrought nightmare, in retrospect everything we’ve just seen becomes mere arbitrary effects leading to a trite “revelation”.

Whenever I’m faced with this kind of disappointment, I’m left wondering how such failures of the writer’s imagination get through the entire pre-production, production, post-production process without anyone making an effort to fix them. I can only assume that these filmmakers don’t see what, to me at least, appear to be fundamental storytelling flaws.

Comments