Movies in Your Head

One of the “advantages” of having a tedious day job which requires a certain amount of concentration but very little thought is that I can spend my shifts listening to my iPod. I’ve recently been addicted to old-time radio shows – among them The Shadow, Gang Busters, Escape, Inner Sanctum, Nero Wolfe, even an excellent western called Frontier Gentleman. The brain has a remarkable capacity for conjuring vivid images, in effect to create a movie in your head from the sounds you hear … I can still recall “visual moments” from radio plays I heard as a kid in England in the early ’60s. And this ability applies to pretty much any kind of sound – not just audio drama, but also music and songs.

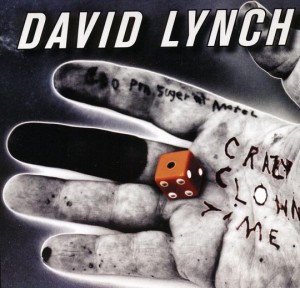

The Inner David Lynch

I’ve been meaning to mention for a while David Lynch’s CD Crazy Clown Time. I’ve been playing it quite obsessively since I picked up a copy over a year ago. Since Lynch seems to have put his filmmaking career on hold, devoting most of his time to proselytizing for TM, this CD is the best way for fans to get a Lynch fix.

Sound has been vitally important to his work since his very first short films; he’s always used sound effects and ambiences like music, giving his films richly textured and nuanced soundscapes. So it was a natural progression for him to become involved in music – teaming with Angelo Badalamenti was a significant step, not simply for the distinctive scores they conjured up for Blue Velvet, Twin Peaks, The Straight Story and so on, but also for the albums they created with Julee Cruise. The sound they developed now seems inseparable from Lynch’s films.

But he also experimented in other ways, with the dreamy ambient sound of Lux Vivens: The Music of Hildegarde von Bingen, which he produced with Jocelyn Montgomery, and the harsh grunge assault of Bluebob which he did with John Neff (who also worked on the Hildegarde project). Lynch has seemed as at home with these audio creations as he has always been with his visual work (film, painting, sculpture and photography).

Crazy Clown Time seems like a remarkable new stage in Lynch’s career; written and performed by him (with additional instrumental support from Dean Hurley, and vocals by Karen O on the opening track, Pinky’s Dream), it’s like a collection of Lynch movies etched in sound … dark, funny, disturbing, at times strangely sweet and infused with emotional yearnings. After INLAND EMPIRE, his masterful summation of everything he’d achieved in more than thirty years of filmmaking, Crazy Clown Time seems to indicate that he’s gone beyond movies into new, more impressionistic creative areas.

Lynch’s lyrics are full of vivid images and a number of the tracks have strong narrative lines; the more familiar you are with his movies, the more clearly you can “see” the songs as movies in your mind.

Lynch’s distinctive speaking voice, with its slight Midwestern nasal twang, proves very supple in the mix of spoken and sung lyrics, as he takes on a series of different personae, shifting from sexual aggression and threatened violence to redneck fun to plaintive longing touched with childlike innocence. Listening to the CD over and over, I find myself immersed in that strange, distinctly Lynchian world, surrounded by his twisted, fearful, sometimes dangerous, sometimes fragile characters, but ultimately shown a glimmer of light and the possibility of transcendent emotion.

A number of the songs have been turned into YouTube videos of variable quality by people other than Lynch. These are a couple of the most interesting:

Crazy Clown Time

Good Day Today

*

The Making of an Exploitation Classic

Another item on my iPod which I’ve listened to repeatedly is a one-hour BBC radio drama from 2010 called Vincent Price and the Horror of the English Blood Beast. Written by Matthew Broughton, a British TV writer, it tells the story (I’m not sure how accurate) of the making of The Witchfinder General and the conflicted relationship between director Michael Reeves and his American star.

Reeves was only 24 when he made this, his third feature, and the play presents him as supremely confident in his abilities as a director – and deeply offended that the film’s American backers have forced him to take Price for the lead. His choice was Donald Pleasance, and that would have made for quite a different movie.

Broughton portrays Price as an insecure actor whose career is on the down slope; Reeves tortures and humiliates him into giving one of his finest performances without the actor even being aware of his own achievement until he finally sees the finished film.

The script is witty and observant of the tensions involved in filmmaking, particularly where ambition runs head on into a limited budget. Blake Ritson gives a terrific performance as Reeves, with excellent support from Kenneth Cranham as exploitation producer Tony Tenser (who narrates) and a fine supporting cast. The only real weakness is Nickolas Grace’s inability to capture Vincent Price’s distinctive voice, though otherwise his performance balances Ritson’s very well.

The play is almost enough to convince me of Reeves’ potential for greatness – a burden his memory has had to carry since his early death at 25. I must admit that I wasn’t terribly impressed with Witchfinder General when I first saw it years ago, but I’ve grown to appreciate it over the past decade or so as I’ve watched it a number of times on DVD, and it certainly has a more serious tone than the Price/Corman Poe series. But I still prefer Reeves’ more imaginative, if somewhat less polished, second feature, The Sorcerers (1967), with Boris Karloff giving his second-last truly great performance (followed the next year by Peter Bogdanovich’s Targets).

Vincent Price and the Horror of the English Blood Beast

Whether or not the play is accurate as history, it’s an entertaining and convincing account of the filmmaking process and an unexpected mainstream tribute to the brief career of Michael Reeves.

Comments