Basil Dearden, Humphrey Jennings, and the fires of London

Growing up in England during the late 1950s and early ’60s, my experience of British film was a mix of now-forgotten B-movies, coarse comedies (I loved the Carry On films, which seem all but unwatchable now), and occasional big productions (Zulu remains a vivid childhood memory). Hammer horror was tantalizingly out of reach, restricted to adult audiences – I can still remember seeing a clip from The Gorgon (1964) on a TV show (I think it was called simply Cinema, part review, part history – it was also where I first saw an excerpt from Wolf Rilla’s Village of the Damned, a film I wouldn’t finally get to see until more than a decade later) and resenting the fact that my older sister had been to see it.

Being a kid, of course, I had no thoughts about the character of my national cinema; it was all just movies and I loved being in a theatre watching. Later, as I began to develop a more serious interest in film, I became aware of the low esteem in which British cinema was held … well, at least by the French. It was considered conservative and unadventurous, contributing little to the art of film. But of course, the same could be said for a lot of countries – even France and the U.S. put out a lot of formulaic, commercially-minded product. And England did have its Hitchcock and its Powell and Pressberger (the latter pair often frowned on for being a little, well, excessive). But it’s true that centuries of imperial rule and rigidly defined class structure had their effect on the indigenous film industry – the British valued understatement and knowing your correct place in the scheme of things.

Transgressive work often gets more respect than conformist work, of course, which is why for a decade or so Hammer and its preeminent director Terence Fisher garnered some serious critical attention alongside the unsurprising condemnation from the forces of social order. But there were always others who, while seeming to work within the parameters of that social order, managed to pick away at it to open a few cracks here and there. This was done most aggressively by the British “new wave” filmmakers of the late ’50s and early ’60s, people like Lindsay Anderson, Tony Richardson, Karel Reisz and so on, who shifted attention from the comfortable middle class to the lower and working classes, people fighting against the constraints imposed by a moribund social and political order.

But there were other directors who tended to work from the “inside”, trying to shift things with lower-key pressure. Basil Dearden was one of these, best known for films like Victim (1961, a careful, sympathetic treatment of homosexuals when homosexuality was still illegal) and Sapphire (1959, a slightly more melodramatic treatment of racism). These two films came as part of a long career which could be described as intelligently commercial. He made comedies and thrillers and contemporary dramas; his most radical film is probably All Night Long (1962), a fascinating if flawed transposition of Othello to the early ’60s jazz scene in London (with Patrick McGoohan terrific as the Iago figure). (These three, along with his great comedy-thriller The League of Gentlemen, were released by Criterion a couple of years back in an Eclipse set titled Basil Dearden’s London Underground.)

As more and more of Dearden’s work has become available on disk in the past decade or so, moving beyond the better-known films, one of the pleasures I’ve discovered is his consistent sensitivity to place, his use of real locations, mostly in and around London. Apart from the stories themselves (often focused on lower class characters, frequently on the fringes of criminality), this attention to location makes many of his films fascinating documents of the post-war period. The Blue Lamp, Pool of London and Violent Playground in the ’50s, and A Place to Go in the early ’60s contain a strong documentary element which adds weight to their concern with social issues.

By the time of The Blue Lamp, Dearden had been working on his craft at Ealing Studios for a full decade, seeming to try on a number of different styles with varying results. He was one of four directors who created Ealing’s classic Dead of Night ghost anthology in 1945; he directed the studio’s most expensive film to date, and first in colour, Saraband For Dead Lovers (1948, also the studio’s biggest money loser), and the rather dull POW movie The Captive Heart (1946). But until recently I had never even heard of his fourth feature, The Bells Go Down (1943), which I just received on DVD from Amazon UK.

The Blitz: Poetry and Propaganda

Released in May, 1943, at the height of the war and just two years after the events depicted, The Bells Go Down is, to say the least, tonally erratic. Dearden directed the film in the middle of doing a series of Will Hay comedies and the first half fits well within that genre, looking forward to Ealing’s “little England” comedies of the late ’40s and early ’50s. Like those movies – Passport to Pimlico, Hue and Cry, The Titfield Thunderbolt – it posits a nation of small, close-knit communities whose inhabitants pull together for the benefit of all.

The Bells Go Down was released just a month after Humphrey Jennings’ dramatized documentary Fires Were Started, so that acknowledged masterpiece could not have been a direct influence, yet there are remarkable similarities between the two films and it’s interesting to consider them side by side. Both deal with units of the Voluntary Fire Service at the start of the Blitz, Germany’s air assault on civilian England which began on September 7, 1940, after the failure of the Battle of Britain to break British resistance. Jennings’ film, however, takes place over a single day and night, while Dearden’s covers a longer period.

In the opening moments of Bells, Dearden and scriptwriter Roger MacDougall (The Man In the White Suit, The Mouse That Roared, A Touch of Larceny) quickly sketch in the community – a “village” in London’s East End, with a chip shop, a street market, a pub – and introduce us to three characters, two of whom decide they need to do their part, the third a petty thief who inadvertently joins them in signing up as he hides from the local constable who wants to arrest him. Jennings, on the other hand, doesn’t spend time on the community, keeping his focus narrowly on the fire station and the men working there; his concern is with the job rather than the individuals performing it.

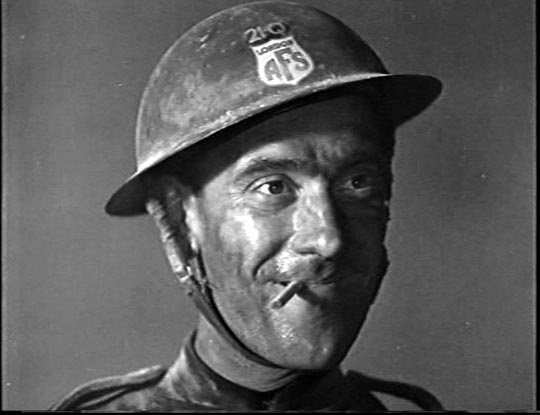

Both films start with the introduction of new men to the firefighting crew (roles performed by well-known character actors in Bells, and by actual firemen in Fires). In Fires, this is Barrett (William Sansom), a former advertising copywriter just transferred to the unit. In Bells, it’s Tommy Turk (Tommy Trinder), whose mum runs the chip shop; Bob (Philip Friend); and Sam (Ealing regular Mervyn Johns), the petty thief whose specialty is stealing barrels of Guinness. These three are taken in hand by fireman Ted Robbins (James Mason), a professional who dislikes his assignment to train these amateurs.

Much of the first half of Bells is given to comic business involving these three – the Guinness thefts, Tommy’s purchase of a greyhound pup he hopes to get rich betting on in the local races. But there are darker elements woven through these episodes. Ted’s parents, who own the pub, are against his relationship with Susie (Meriel Forbes), one of the fire service telephone operators who Ted’s mother feels is beneath them; one of the other volunteers, Brookes (William Hartnell – the first Dr. Who), was in the International Brigade in Spain and he tells the others what they can expect from the fascists.

The first half of Fires, in contrast, details the men practising with their equipment, while Barrett is shown around the area, which includes docks on the Thames where a ship is being loaded with vehicles and ammunition for transport overseas. The mild dramatic tension between Ted and the recruits is absent here, as Barrett, despite class differences (he is obviously better educated then the rest of the crew) is absorbed quickly into the group. This is the difference between Jennings’ documentary sensibility and the requirements of commercial entertainment.

But these differences all but vanish at the halfway point of both films. With the arrival of night and the sound of air raid sirens, both films become intensely focused on the job these men are required to do. The bombs drop and fires start and the crews are faced with burning warehouses, their work complicated by bombs continuing to fall and water supplies being cut off by explosions. Bells comes into focus at last, and surprisingly takes on much the same power as Fires; the looseness and comedy disappear, along with comedian Tommy Trinder, the ostensible star – he pops up for one or two quick lines just to remind you he’s there, but what matters now is the group as a single interconnected unit performing a dangerous task, reflecting the major themes of British war propaganda, with all classes pulling together in a single cause.

There are still stylistic differences, of course. Jennings, influenced by Soviet film, creates a series of monumental images of everyday heroism, his firemen symbolizing the power and determination of ordinary people facing the terror of aerial bombardment; these men go calmly about their work, solving problems, putting themselves in harm’s way to get the job done, sacrificing themselves for the sake of their mates. Dearden also deals with these narrative elements, but he builds them into an impressive action sequence which must have used every resource Ealing had available: documentary footage of fires is blended with live action location work, shots staged in the studio with rear-screen projection, and some very large and elaborate miniatures. While it lacks Jennings’ poetry, Dearden’s extended action sequence is a thrilling piece of entertainment with some implausible but nonetheless emotionally resonant bits of “drama” mixed in.

Finally, both films climax with the death of a fireman – surprising and unexpected in Bells; matter-of-fact and inevitable in Fires – and end with the exhausted calm of morning and the people of the city gradually emerging into the shattered streets.

The Bells Go Down is in many ways an awkward film, but for all its initial comic bluster and its touches of sentiment, it ends up paying sincere tribute both to the firemen (after their performance during the first night of the Blitz they’re given a new assignment and Ted happily accepts command of these men whom he now respects) and to the city they fought to defend. In effect, this piece of commercially produced home front propaganda has a similar impact to Jennings’ more accomplished, and certainly more artful film.

*

Fires Were Started (and its slightly longer original version, I Was A Fireman; both available on the BFI’s The Complete Humphrey Jennings Vol 2 Blu-ray), like much of Jennings’ work, is largely shaped by music. Not only does he weave music throughout the film, both background score and diegetic songs, but the film itself is structured in three movements, like a symphony: the long calm opening introducing the men and their work; the intensely dramatic night, full of danger and ultimately death; and the melancholy quiet of the morning aftermath and its contemplation of the cost in lives lost. I can’t help but think that Jennings must have been a major influence on Terence Davies, another poetic filmmaker who uses music to unify his films and to anchor their rich emotional content.

Comments

I wondered if Barrett could have been a CO as many joined the fire service. His cultured addition to the team and the One man went to mow episode was a highlight of the film for me

That’s certainly a logical possibility, although the film itself never addresses the point.